|

I came across a research challenge in Ragtimers Club, a Facebook special interest group. A series of posts hinted that an obscure young pianist, unfamiliar to everyone in the group, had posed as Scott Joplin, the King of Ragtime, during several 1913 performances across Southeast Kansas.

After two partial days of trying to pinpoint the pianist's identity, beyond the partial name available to me in Ragtimers Club, I identified a suspect. I also had a problem. My suspect was another piano-playing con-man active during the 1930s and '40s. Joplin's Southeast Kansas impersonator, if indeed there was one, had only first and middle initials and a last name--C. W. Wilburn. My suspect shared the Wilburn surname but had a given name beginning with C and no middle name or initial. I had to admit, if only to myself, that the odds were against me. Yet the more I struggled to piece together what looked like the right biographical records, ruling out other men's records who shared the name, and the more I researched this other Wilburn's performance history, the more convinced I became that I needed to see if I could connect the two men. Anyone with the audacity and skill to assume a false identity as a public performer and to get away with it for nearly two decades would not have hesitated to pose for a few weeks as Scott Joplin in small-town Southeast Kansas. This is the story of my search--of my effort to link the Southeast Kansas King of Ragtime with the Prince of Music. Scott Joplin's only identified trip through Oklahoma occurred roughly three years and four months before Oklahoma became the 46th state.

When I began this project, I intended to provide brief historic and ragtime context for Joplin's visit and to document the visit itself--a simple, straightforward project. That remains a substantial portion of what appears below. Eventually, I realized that the tour through territorial Oklahoma extended beyond the borders, altering the established Joplin timeline. For that reason, I expanded my scope. As I pursued new ideas, I researched additional angles. New findings led back to an unanswered question Ed Berlin asks in King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era (2nd ed, 2016), and I will propose a possible answer to that question. Hopefully, the gradual evolution of this project has increased its significance. Anyone wishing to read only the Joplin findings may do so by scrolling down to "The Joplins Travel Through Indian Territory." Yes, Freddie Joplin must have accompanied her new husband on these travels. However, the earlier material will provide a broader understanding of what the Joplins would have experienced during their travels, and I will occasionally allude to that cultural background when discussing the Joplins. Scott Joplin could not have conceived and composed a more suitable musical and dramatic finale for Treemonisha. Ed Berlin provides an excellent overview of Joplin’s accomplishment: Treemonisha stands on a bench and calls the steps, sometimes assisted by Lucy. She leads the townspeople on two levels: on the literal level, she calls the steps for the dancers of “A Real Slow Drag”; metaphorically, she guides the people to a better life—“Marching onward.” But they march not to the military strains of a John Philip Sousa; rather, they march to a characteristically African American music—a rag, a slow rag. This finale is a fitting and glorious conclusion, summing up Joplin’s philosophy that African Americans choose education as their means to a brighter future. (King of Ragtime, 2016, 270) Although Berlin’s multifaceted interpretation encompasses the message inherent in Joplin’s lyric and the culturally appropriate music genre in which Joplin couches that message and dramatically concludes the opera, there is more. This slow march forward to a brighter future mirrors the Hampton-Tuskegee ideology—a way of thinking repeatedly driven home to the schools’ students, to potential Northern benefactors, and to white Southern neighbors, a way of thinking adopted by many other African American schools throughout the former slave states, including Sedalia's George R. Smith College, which Joplin had attended.

With Parson Altalk’s failure to address his parishioners’ earthly needs, such as overcoming superstition and dealing with the conjurors, Treemonisha’s neighbors need a leader, someone capable of guiding them forward. Long before introducing his failed leader, Joplin had set the scene for his true leader’s arrival. In the opera’s preface, he explained that whites had left the plantation after the Civil War, leaving it to be run by Ned, a trustworthy servant. Living in dense ignorance, symbolized by the dense forest surrounding the plantation, the freedmen were left “with no one to guide them as they struggled to adapt to unaccustomed freedom. Childless Ned and Monisha prayed for an infant who could grow up educated and able to “teach the people around them to aspire to something better and higher than superstition and conjuring.”

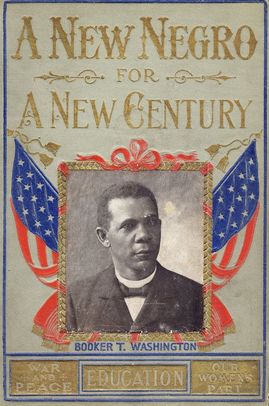

In the opera’s opening number, Treemonisha reprimands the conjuror Zodzetrick for having “caused superstition and many sad tears,” and viewers and listeners recognize her potential to realize Ned and Monisha’s dream. Indeed, before the opera’s opening, Treemonisha had achieved small scale teaching success. She had taught Remus to read, enabling him to chide Zodzetrick, not only by arguing that the conjuror cannot fool the level-headed Treemonisha, but that he can no longer fool Remus: To read and write she has taught me, and I am very grateful, Although education might initially come from whites, Joplin shows that a black with basic education could become the educator, as did Booker T. Washington and so many graduates of schools such as Hampton and Tuskegee. Speaking of Tuskegee, Samuel Chapman Armstrong had once written, "It is a proof that the Negro can raise the Negro" (Qtd. by Washington in The Story of My Live and Work, J. L. Nichols & Co., 1901, 372). Washington attributed much of this success to his people's desire to learn from their teachers as he had learned from Armstrong: "Often hungry and in rags, making sacrifices of which you little dream, the Negro youth has been determined to annihilate his mental darkness. With all the disadvantages the Negro, according to official records, has blotted out 55.5 per cent of his illiteracy since he became a free man" ("Negro Education Not a Failure," Booker T. Washington Papers. Univ. if IL Press, 1972, II: 431).

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed