|

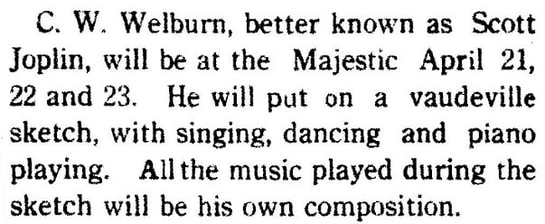

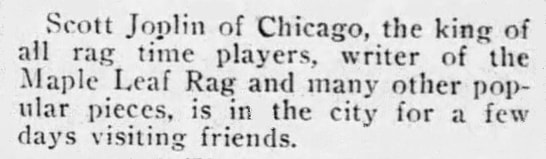

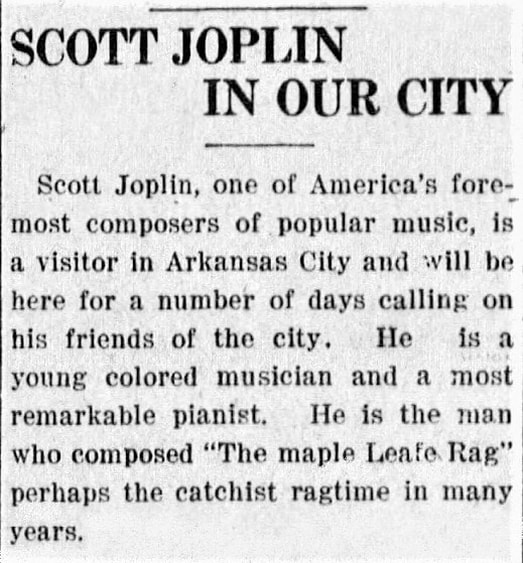

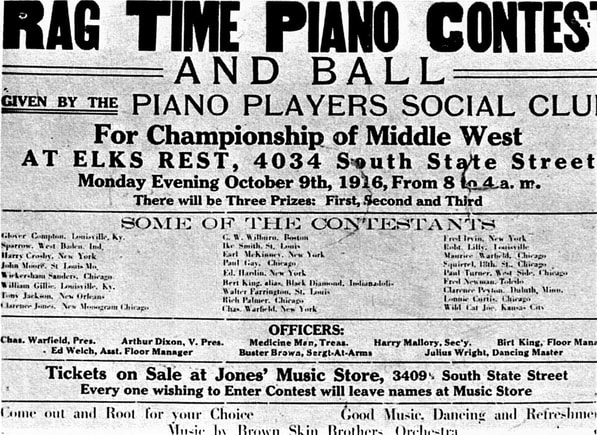

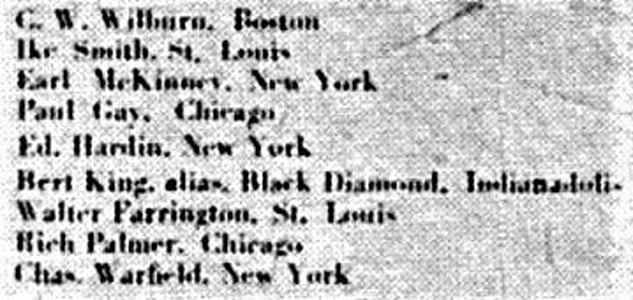

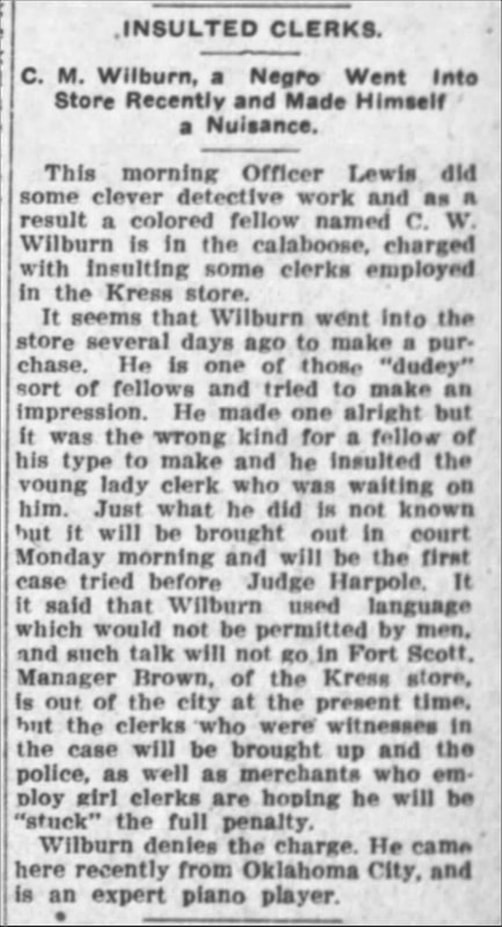

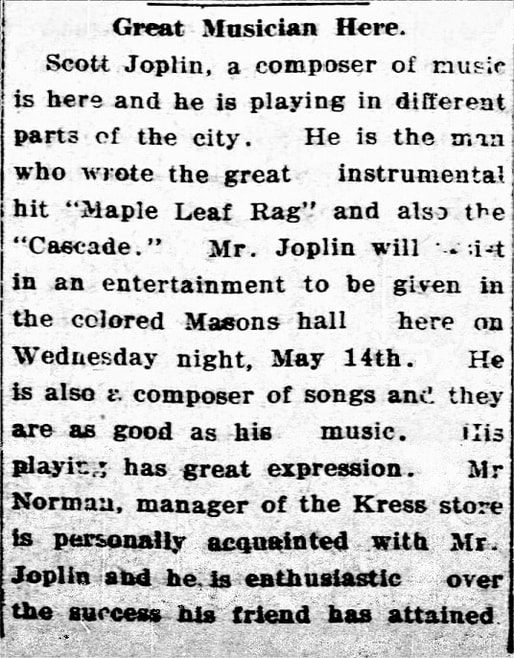

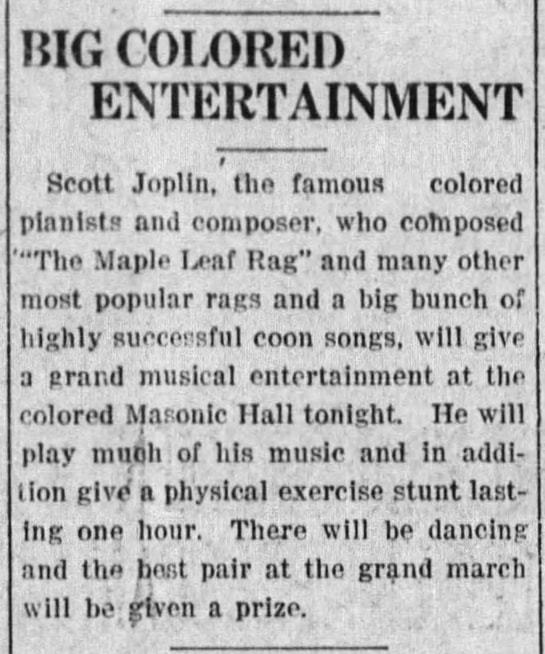

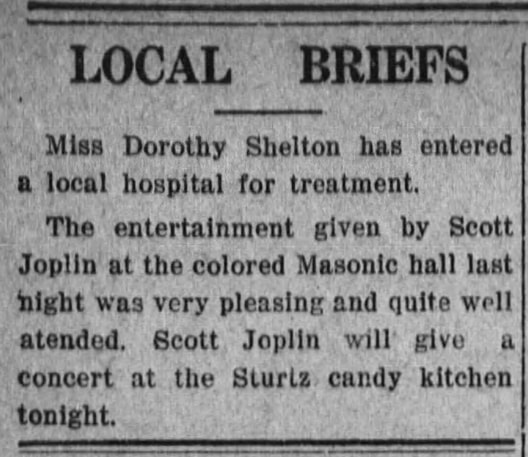

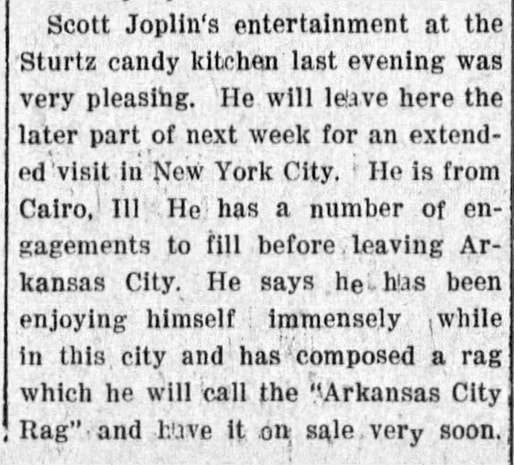

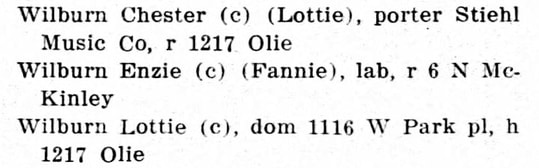

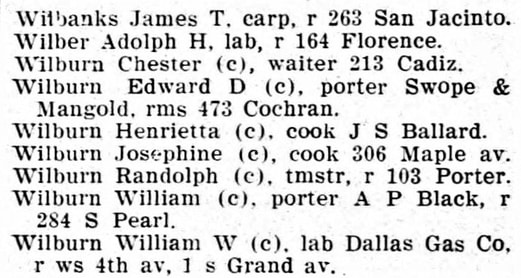

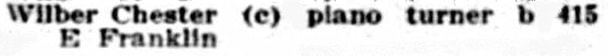

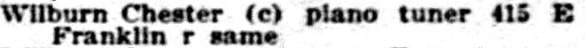

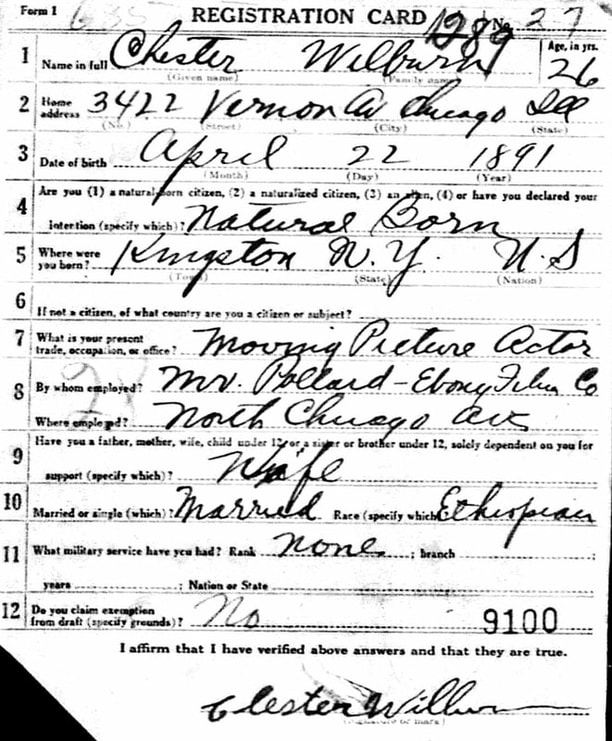

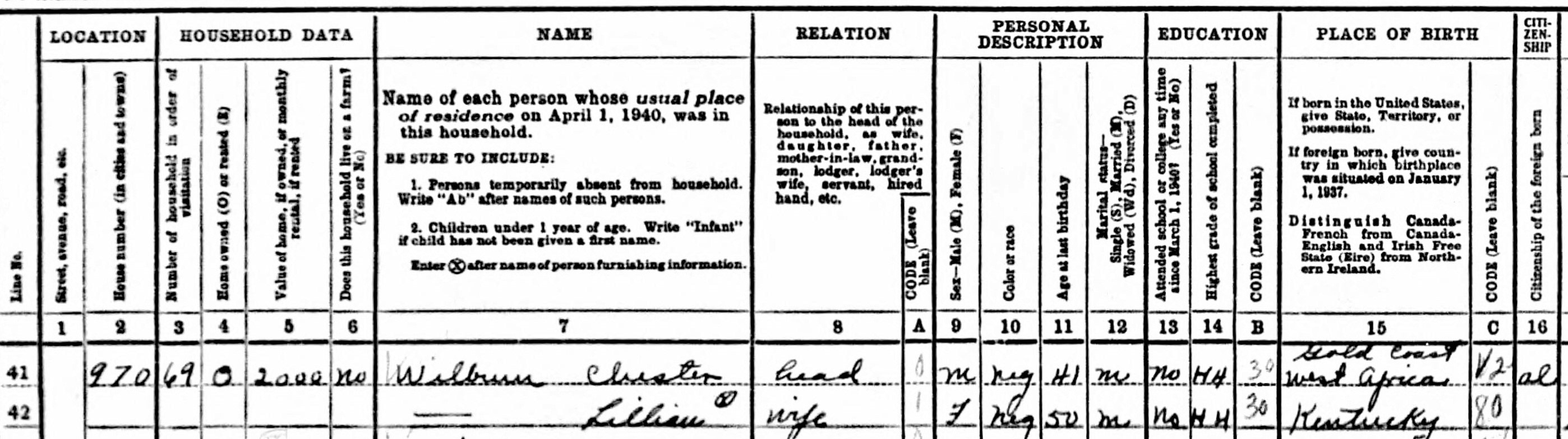

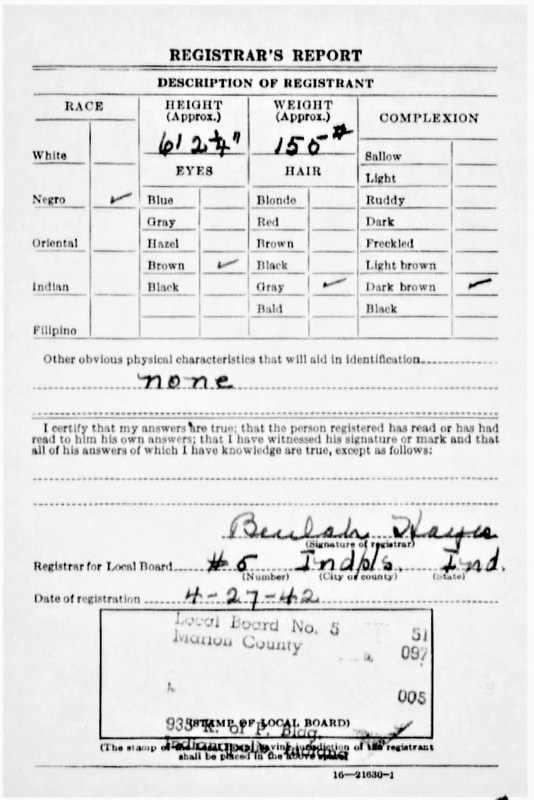

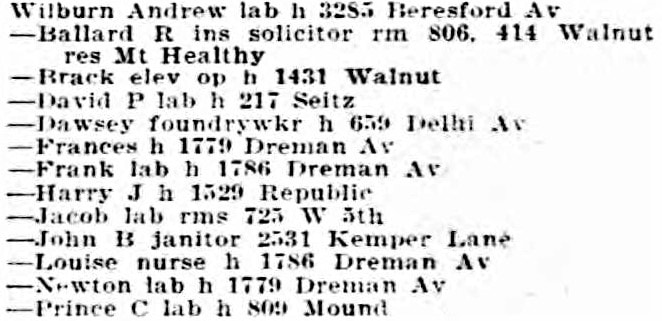

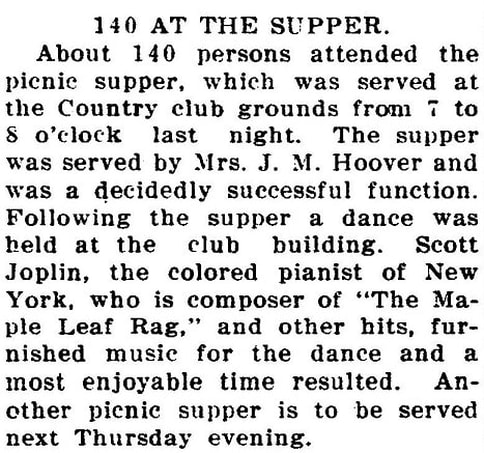

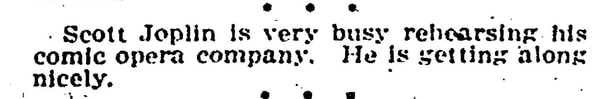

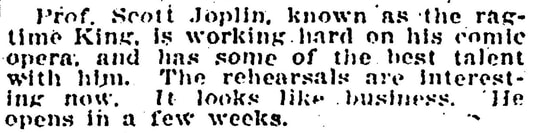

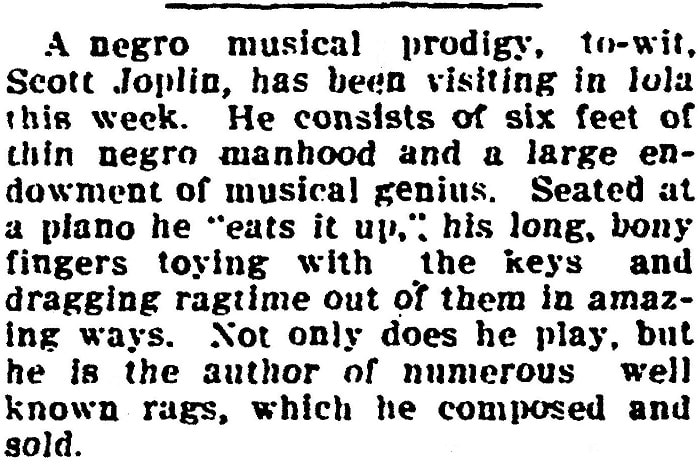

I came across a research challenge in Ragtimers Club, a Facebook special interest group. A series of posts hinted that an obscure young pianist, unfamiliar to everyone in the group, had posed as Scott Joplin, the King of Ragtime, during several 1913 performances across Southeast Kansas. After two partial days of trying to pinpoint the pianist's identity, beyond the partial name available to me in Ragtimers Club, I identified a suspect. I also had a problem. My suspect was another piano-playing con-man active during the 1930s and '40s. Joplin's Southeast Kansas impersonator, if indeed there was one, had only first and middle initials and a last name--C. W. Wilburn. My suspect shared the Wilburn surname but had a given name beginning with C and no middle name or initial. I had to admit, if only to myself, that the odds were against me. Yet the more I struggled to piece together what looked like the right biographical records, ruling out other men's records who shared the name, and the more I researched this other Wilburn's performance history, the more convinced I became that I needed to see if I could connect the two men. Anyone with the audacity and skill to assume a false identity as a public performer and to get away with it for nearly two decades would not have hesitated to pose for a few weeks as Scott Joplin in small-town Southeast Kansas. This is the story of my search--of my effort to link the Southeast Kansas King of Ragtime with the Prince of Music. Background from Ragtimers Club I begin with the material inspiring this search. With an exception or two, the newspaper articles and announcements immediately below appeared originally on Facebook as transcriptions. I now supply the newspaper and book images. Some readers will have seen, and a few will have commented on, the articles when they appeared on Facebook. Even so, review cannot hurt, especially because they were posted in two threads nearly a year apart, the more recent nearly three months ago. Other readers will be seeing this background material for the first time and will surely need it. September 2019 On September 25, 2019, Ed Berlin raised an intriguing question by posting the following article. Was this an error, or was an unknown pianist named C. W. Welburn posing as Scott Joplin, the King of Ragtime? Group members brought up a variety of points. Joplin had been living in New York City since 1907. His health might already be declining, due to the syphilis that would take his life within four years of the Southeast Kansas appearances. Joplin's name would draw a larger audience than that of an unknown pianist, so someone might have borrowed his name. However, if another pianist posed as Joplin, it seems unlikely that imposter would have revealed his real name. What if this was a mistake? What if Joplin had gone on tour in Kansas in 1913? Bryan Cather brought up two other Joplin appearances--one the previous month, the other the next month. Both articles raise issues. Joplin had been living in New York, not Chicago; and, at roughly 45, he was middle aged, not young. Mistakes happen, and such might have been the case with Joplin's current residence. Relative age--young or old--can be in the eye of the beholder. Nonetheless, such discrepancies, combined with "Welburn, better known as Scott Joplin," caused one group member to declare this "Early Fake News." August 2020 On August 4, 2020, Ed Berlin started a new thread, reposting the article that had started the original discussion, pointing out a Chicago ragtime contest poster in Blesh and Janis' They All Played Ragtime, and transcribing several articles sent to him by Eric Bianchi. From Peabody, Kansas, the first group of articles introduces us to C. W. Wilburn, whom we first encountered as the mysterious "C. W. Welburn, better known as Scott Joplin." The poster, according to Berlin, can be found on an unnumbered page two pages before page 81 of the 1979 edition of They All Played Ragtime. It appears on the same page of my 1966 edition from ebay. The poster reveals that C. W. Wilburn was in Chicago at least briefly in October 1916. It also tells us that he was from Boston, a potential research clue. The additional newspaper items offer further information: Since this item appeared on Thursday, March 13, Wilburn and Carroll had visited Peabody the previous Friday, March 7, to arrange the March 14 performance. Reading about the preparation for Wilburn and Carroll's performance at Peabody's Masonic opera house, we see nothing alarming. Wilburn and Carroll must have impressed their local contacts when they visited in early March, for the paper reporting their trip to town describes them as "two enterprising young colored men." Peabody seems to have cause to look forward to the troupe's minstrel show. Although minstrel shows were not normally comprised of all original songs and dance music, instead using many traditional and popular tunes and songs, Wilburn's claim of having written all the show's music might have contributed to the positive impression and to expectations of an original show produced by talented managers. The August 2020 Ragtimers Club thread next places Wilburn in Fort Scott, Kansas, during early April. We begin to see Wilburn as someone other than one of "two enterprising young colored men" who had arrived in Peabody nearly a month earlier to arrange for their show at the Masonic opera house. His "dudey" appearance and behavior offended a clerk and ran him afoul of the law. If he--or he and S. Carroll, planned to arrange a Fort Scott performance, they lost that opportunity. Over the next two days, the Fort Scott press reported on the case between the Kress store employees and Wilburn: Unfortunately, we never learn the precise nature of Wilburn's verbal transgressions. When Monday's trial day arrived, he had already skipped town: The last group of articles Ed Berlin posted to the August 2020 Ragtimers Club thread report on Scott Joplin's May 1913 visit to Arkansas City, Kansas. At least, that is what they appear to report. Berlin had previously dealt with this article in the second edition of King of Ragtime. He had clearly been surprised by the timing of such a trip. Joplin had been busy rewriting Treemonisha in New York and would announce the next month that the opera was in rehearsal, with an opening performance scheduled for July 14 in Bayonne, New Jersey. Working the Arkansas City trip into Chapter 17: "The Elusive Production, 1911-1913," Berlin begins with the telling verb "seems": "In May 1913, Joplin seems to have taken time off from his work on Treemonisha to travel to Arkansas City, Kansas." Rather than ignore the trip far from New York, Berlin offers reasons that could logically explain the trip. Several years later, armed with additional information, Berlin posted the following three articles, prefacing them with a list of details that had recently led him to conclude that Joplin "had not gone to Kansas." Joplin would not have told people he was from Cairo, Illinois or that he would soon make "an extended visit to New York," when he already lived there; he would not have included a "physical exercise stunt lasting one hour" in his performance. Somebody had been posing as Scott Joplin, the King of Ragtime, in Southeast Kansas, and we had only one suspect, C.W. Wilburn, the man the Allen County Journal had identified as "better known as Scott Joplin. In Search of C. W. Wilburn The posted items offer few clues. Two Fort Scott papers report Wilburn had recently arrived from Oklahoma City. The Chicago ragtime contest advertisement indicates that he is from Boston. The Arkansas City Daily News hints he might be from Cairo, Illinois. From Southeast Kansas papers, we know he is young, can play ragtime, and can sing. We know he might have composed some or all of the music for a minstrel show. We know he has minimal knowledge of Joplin. He knows Joplin wrote The Maple Leaf Rag but not where Joplin lives in 1913 or had lived in the past. We know he is a scoundrel and liar. We can also see his uncanny ability to impress the gullible townsfolk. He even appears to have had sense of irony enough to make a point of his personal acquaintance with Arkansas City's Kress store manager or to get the manager to do so after Wilburn had been forced to flee Fort Scott following the Kress store incident. A small amount of this knowledge is searchable. I began by searching newspaper archives for C. W. Wilburn but found only what had already been posted on Facebook. I turned to ancestry.com. By limiting my first search to Oklahoma City directories, I located a Chester Wilburn and wife Lottie in 1911, with their entries followed by (c) for "colored." Although none of the four Wilburns in the directory excerpt above appear in the 1912 directory, possibly indicating the two couples or families were related and moved together, I decided to see if I could locate Chester Wilburn's birth date or age. A search for older public documents turned up a July 5, 1910 Kaufman, Texas marriage record for Chester Wilburn and Lottie Crosby. Kaufman lies about 35 miles southeast of downtown Dallas. While this might be the same couple, the record is not accompanied by a license or certificate and indicates neither race, nor birth dates/ages. Because of Kaufman's proximity to Dallas, I checked the Dallas directory and located a group of Wilburns in the 1907 directory, including a Chester: Again, this may or may not be the Chester Wilburn in Oklahoma City or C. W. Wilburn in Southeast Kansas. My attempts to establish a family relationship between the other Dallas Wilburns and Chester have not yet succeeded. Several of these Wilburns appear year after year, before and after the 1907 directory. Chester appears only once. A Chester Welborn (c) does appear in neighboring Fort Worth's 1912 directory as a clothes cleaner, presser but is less likely to be the same man due to two incorrect letters in his surname. Nonetheless, he might be the same person. Trying Missouri, I located records for a Chester Wilber and Chester Wilburn, piano tuners. Despite the somewhat different surnames, these must be the same man. Occupation and address match. I suspect the second entry provides the correct name; we will see Chester Wilburn working as a piano tuner again although in another place. With no luck locating a birth date, I decided to try Chicago where C. W. Willburn competed in the 1916 ragtime competition. An Ancestry search for Chester Wilburn yielded four results: another marriage record, a World War I draft registration, a 1920 U. S. Federal Census record, and a 1923 city directory entry. Things were looking up although I could not readily conclude that Chester Wilburn was the C.W. Wilburn who posed as Scott Joplin in Southeast Kansas. On November 6, 1916, less than a month after the Chicago ragtime contest to determine the champion ragtime pianist of the Middle West, Chester Wilburn, age 25, married Minnie Jane Stewart, 38, in Chicago. Chester Wilburn's age tells us he was born in 1891 or very early 1892, which would be appropriate for him to have been referred to as a young man while performing in 1913 Southeast Kansas. Again, no marriage license or certificate is available online to provide further information such as birthplace or race. A 25-year-old man marrying a 38-year-old woman comes as a surprise, but this will not be the only time Chester Wilburn marries a considerably older woman. The World War I draft registration finally provides a precise birth date: April 22, 1891. The age on the draft registration corresponds with the marriage record five months earlier. Age 25 the past November, Chester has had another birthday (April 22), making him 26. If C. W. Wilburn had lived in Oklahoma City before going to Southeast Kansas, as he said he had, these records could conceivably belong to the same man. Of course, this leaves us wondering what happened to Lottie, Wilburn's first wife. I cannot answer that question. This record contains several other questionable or interesting pieces of information. When competing in the ragtime piano championship, C. W. Wilburn had identified Boston as home; Chester Wilburn lists Kingston, New York as place of birth. Granted, he could have been born in Kingston and later lived in Boston. On the other hand, C. W. Wilburn might have said ScottJoplin was from Cairo, Illinois because Willburn, himself, was from Cairo and did not know Joplin's home. I have not been able to trace Chester or C. W. to Boston, Kingston, or Cairo, raising the possibility that none of the three places may be accurate. Chester Wilburn also chose an atypical word to identify his race. In 1913, "Negro" or "Colored" were far more common that "Ethiopian." If also C. W. Wilburn, perhaps his minstrel show background influenced his use of the outdated term.

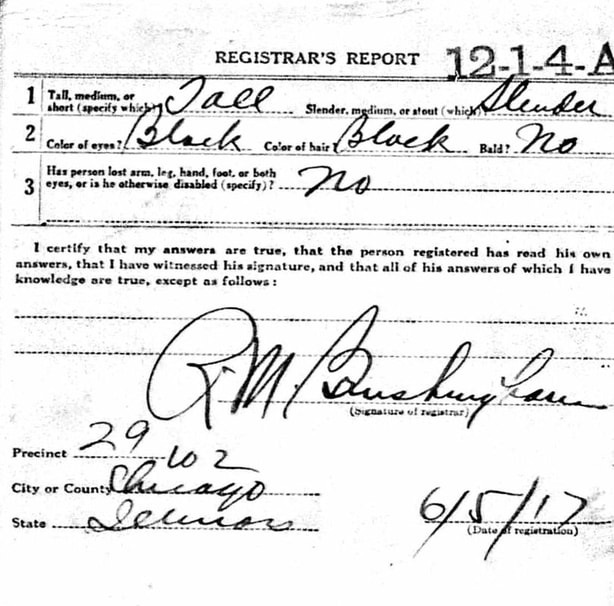

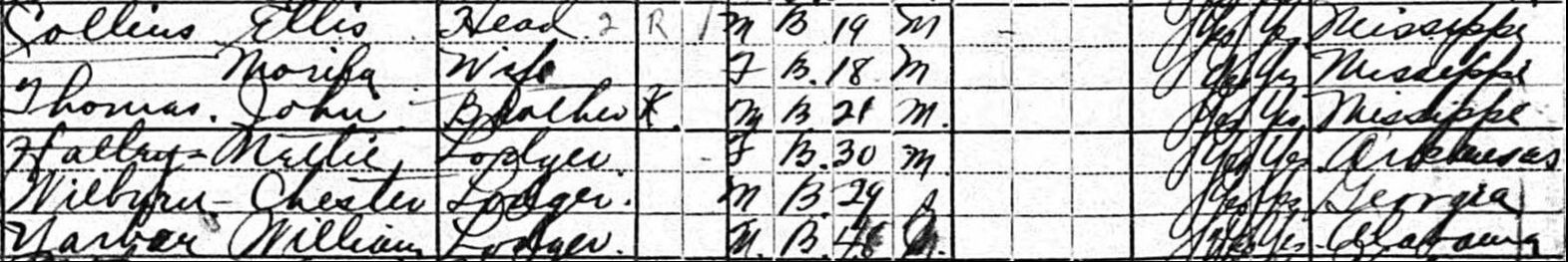

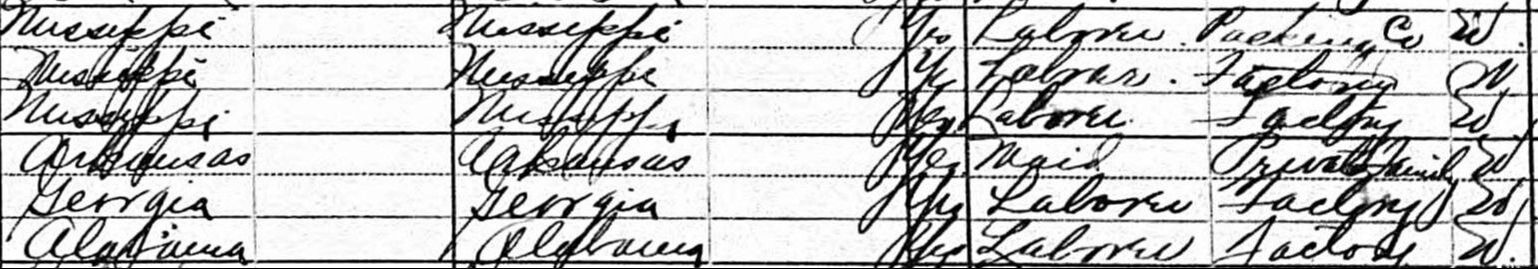

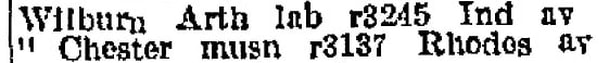

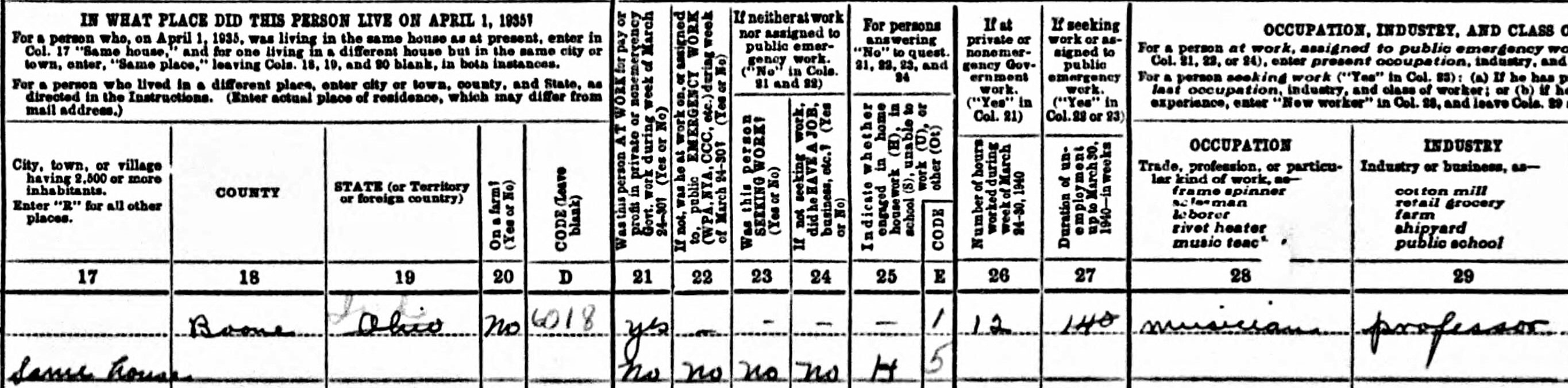

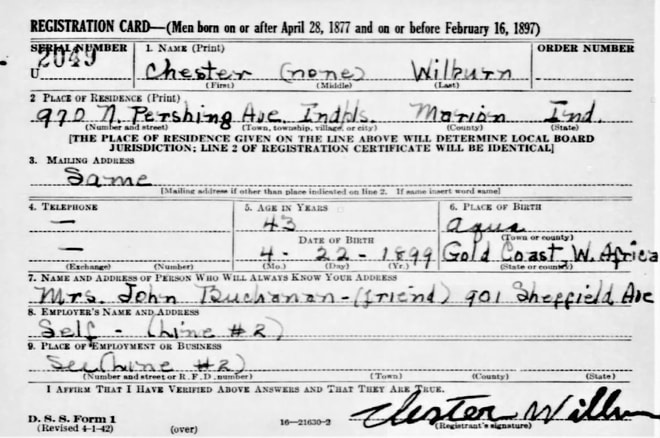

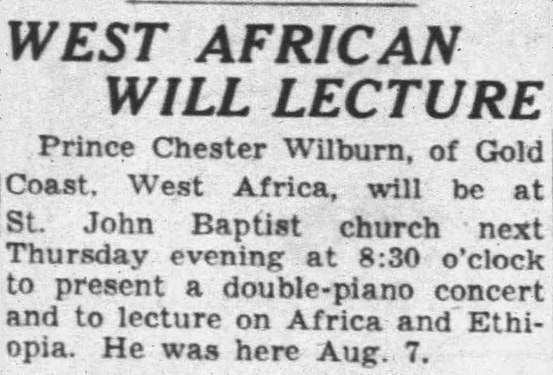

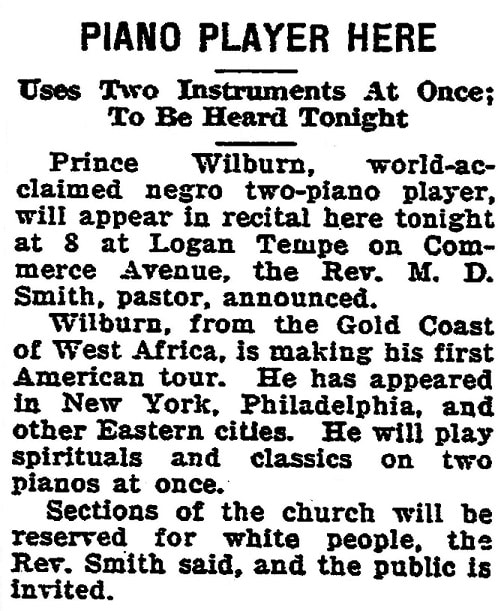

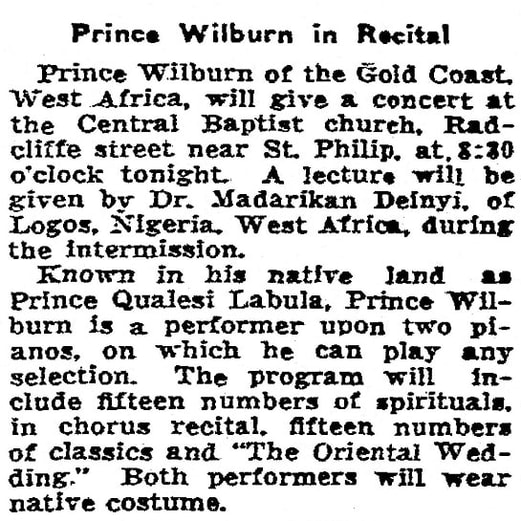

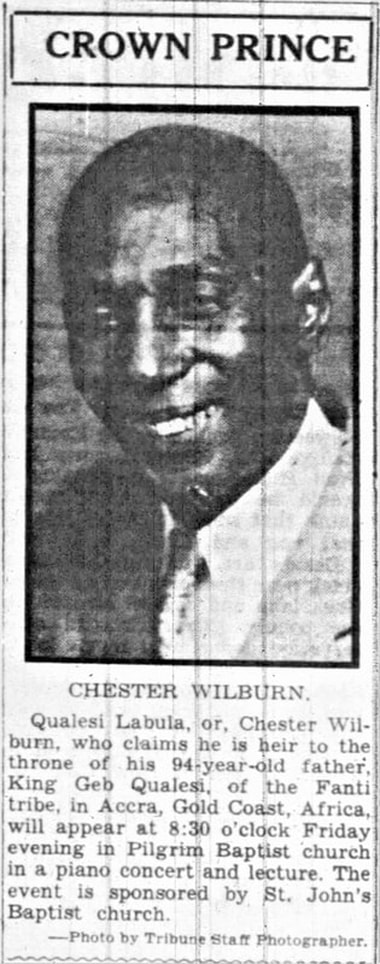

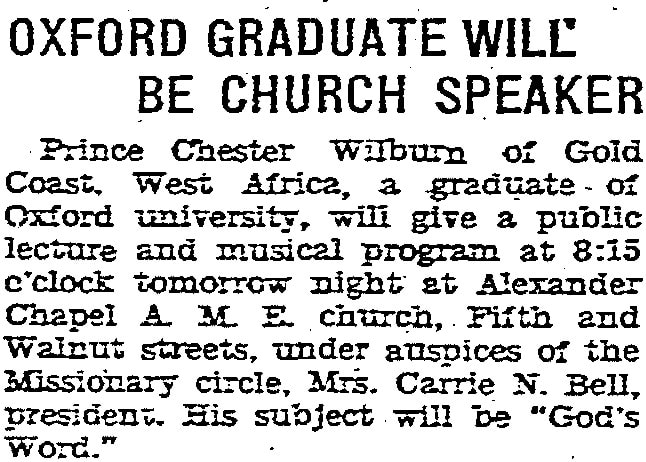

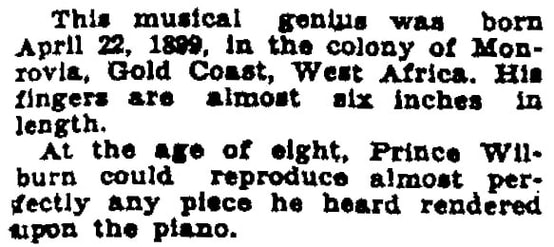

Along with the birth date, the other most significant information on Chester Wilburn's draft registration will eventually prove to be his signature and his physical description. Chester Wilburn next shows up in the 1920 U.S. Federal Census for Chicago, which I have divided in half for legibility: Chester is living in a boarding house at 3137 Vernon Avenue, not far from his 3422 Vernon Avenue address when he registered for the draft in 1917 at age 26. The proximity to his previous address and his age of 29 indicate that this is probably the same Chester Wilburn. However, he is single again and lists himself and his parents as all born in Georgia, yet another possible birthplace. We have seen Chester reinvent himself several times, but the factory job has a likely explanation. He will later say he worked in a Chicago piano factory. One other Chicago record has surfaced--a 1923 city directory listing: Here Chester sounds more like the C.W. Wilburn who performed in Southeast Kansas and competed for the ragtime championship of the Middle West. Chester now seemed to disappear from public records until 1940. Early in my research, I had found a W. Chester Wilburn working as a piano tuner in El Paso, Texas, for several years in the 1920s but soon ruled him out when a more thorough search of El Paso records revealed that W. Chester Wilburn was white. Chester Wilburn's story would soon grow more interesting. Although I have not located him in the 1930 U. S. Federal Census, a 1940 census record for a black Chester Wilburn identifies his occupation as "musician" and the industry as "professor." He is living at 970 North Pershing Avenue, Indianapolis and has a wife named Lillian. Chester is said to be 41, 8 years too young to be the Chicago Chester Wilburn born in 1891, but I have seen many people shave off years on census records as they grew older. Lillian's age is given as 50. The most puzzling census information is Chester Wilburn's new birthplace: Gold Coast West Africa. If this is the same Chester Wilburn, he has outdone himself this time. Chester's citizenship is marked "al," presumably for "alien." Lillian is said to have been born in Kentucky. The house, valued at $2000, belongs to Lillian, who reports she lived there in 1935 while Chester was living in Boone County Ohio or Indiana. "Ind" is penciled above Ohio. Since there is no Boone County in Ohio, Boone County, Indiana is probably correct and incompasses an area to the immediate northwest of Indianapolis. Column 26 asks how many hours each person worked between March 24 and March 31. Chester indicates 12 hours. Lillian does not work. Column 27 asks for the number of weeks of unemployment leading up to March 30. Chester apparently answered "140," but for some reason, it is marked out. Two columns cut off from the graphic ask for the number of weeks worked in 1939 and the amount of money earned. Chester's answers are 40 hours of work for the year and 40 dollars earned. We have to wonder how they supported themselves. The fact that Lillian was living in the house in 1935 and Chester was not tells us that they married after 1935. Although I will look into that, a more urgent task is determining if this musical Chester Wilburn is the same one who lived in Chicago years earlier. Chester Wilburn's Chicago World War I draft registration provided a birth date, signature, and physical description, and that April 22, 1891 date of birth would have exempted him from the World War II draft (for men 45 and under). Fortunately, for research purposes, Wilburn did register again. In keeping with the age (41) given in the 1940 census, Chester Wilburn's April 27, 1942 draft registration gives his birth year as 1899, but the day and month (April 22) coincide with his WWI registration, which indicated an 1891 birth year. Although one form was completed in cursive and one printed, the signatures at the bottom of the first page match. The 1917 form describes Chester as tall and slender, and this 1942 form indicates that he is slightly over 6' 2" and a quarter century later still a slim 155 pounds. Chicago Chester and Indianapolis Chester are the same man despite the fact that he should have celebrated his 51at birthday 5 days before registering. His reason for registering isn't clear. Perhaps he registered because he had lied about his age in the 1940 census, perhaps because he was also lying to Lillian. Again, Wilburn indicates that he was born in the Gold Coast, West Africa, and this is now an even less convincing lie than before. Surely, he did not forget his city of birth. Aqua should surely be Accra, the capital of today's Ghana, once part of the British Colonial Gold Coast. For anyone who might wonder, I cannot explain his listing Mrs. John Buchanan as the person who would always know his address. Checking into this, I found John and Rowena Buchanan living at 902 Sheffield Avenue, which intersected Wilburn's street at the end of his block, close enough that Chester and Lillian, John and Rowena could be considered neighbors. Chester had made an easy error when giving their address as 901. Next, I backed up in search of a marriage record, hunting for an Indianapolis marriage of Chester Wilburn to a woman named Lillian, surname unknown. When I found nothing, I decided to find Lillian's name when she married Chester, whether a maiden name or a previous married name. Using her first name and her address at 970 N Pershing Av, I eventually learned that she was born Lillian Leonard, January 1, 1879, married William Hunt in 1903, lived with William at 970 N. Pershing most of the years of their marriage, and had been a widow for a year and a half when she married Wilburn. According to her birth date, she was 61, not 50, in 1940, making this all the stranger that Chester gave his age as 41. Armed with Lillian's name at the time of marriage, I located Chester and Lillian's marriage record and had no idea what to think about what I found. Again, there is no license or certificate, so I have copied and pasted the information from their Indianapolis, Marion County marriage: Name: Prince Wilburn Gender: Male Marriage Date: 18 Nov 1936 Marriage Place: Marion, Indiana, USA Spouse: Lillian Hunt Although Chester Wilburn had made himself younger and regularly changed his birthplace, his name had remained consistent aside for appearing as C. W. Wilburn in Southeast Kansas, if that had, indeed, been the same man. Despite appearing as Prince Wilburn in the Indianapolis marriage record, he appears in two city directories as Chester Wilburn; I have not found others. In 1945, he worked for the Atlantic District of General Motors Corporation and in 1949 as a carpenter: He and Lillian had remained at the same address, and sometime between 1945 and 1949 had been joined by a Mrs. Claudia Wilburn, possibly Chester's elderly mother although I have not been able to trace her. Given the matching signatures and birth dates on Chester Wilburn's WWI and WWII draft registrations, along with Wilburn's marriage to Lillian Hunt fewer than three months after this performances, it appears that he had assumed another identity as a piano-playing West African prince, even marrying Lillian under the name Prince Wilburn, a name not seen in the Chicago public records. How long had Wilburn been posing as an African prince? What was the nature of Prince Wilburn's double-piano concerts? Other articles will answer some of the possible questions. Dozens of articles report Prince Chester Wilburn's performances not only in Indiana, but also in Michigan, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia. Many of these articles do little more than announce a performance place, time, and date, but others provide details--some contradictory--that add to our understanding of a man who hoodwinked the public for nearly two decades. To best show this con man's history, I will present the articles largely in chronological order, starting in Knoxville, Tennessee where I found the earliest coverage. My goal is to demonstrate various aspects of Chester Wilburn's story, including its evolution, its glaring contradictions, and its occasional false music claims. From 1930 to 1948, the three constants were Wilburn's title of nobility, his origin in the Gold Coast of West Africa, and his simultaneous performance on two pianos. Nearly anything else proved subject to change. Because so many articles contain nearly identical information, I will skip years here and there but will occasionally summarize his travels during those missing years. The earliest located article declares that Prince Wilburn is making his first American tour: Like the majority of Chester Wilburn's performances, this one occurred in an African American church. The article conveys the impression that the Prince has recently come from several major concerts. Despite many claims of Eastern city performances, including alleged critical reviews, I have found no substantiating evidence, no record of his being in or performing in any part of the East other than Virginia and Southeastern states. Two days later, the News-Sentinel announced another performance at Knoxville's Rogers Memorial Baptist Church on June 5, providing a brief description of Wilburn's Logan Temple concert: Knoxville [TN] News-Sentinel, June 4, 1930, p. 12 Chester Wilburn may have been an impressive pianist, but we see him using a stunt to impress his listeners. Throughout the 1930s and '40s, his two-piano performance received the most notice. Only rarely did a newspaper mention a specific music title as in the above excerpt. "My Lord is Writing All the Time" can be found in De Capo Press's The Books of American Negro Spirituals, a composite of two earlier collections compiled by brothers James Weldon and J. Rosamond Johnson. Wilburn could not have chosen a more appropriate spiritual because its lyric focuses on the hope of ascending to heaven but repeatedly cautions that God is always watching and documenting: "Oh, He sees all you do, He hears all you say, My Lord's a-writin' all the time." The journalist's words "his interpretation of Hungarian Rhapsody, No. 7" makes me wonder if Wilburn was playing Liszt or possibly a ragged version of Liszt. Few, if any, members of Wilburn's audiences would have known one Lizst piece from another. Perhaps Wilburn was ragging No. 7; perhaps he was playing something else altogether, such as Julius Lenzberg's Hungarian Rag (1913). This is one of those questions we will never answer. As we have already seen, Wilburn had no problem lying, and his lies appear to include the existence of major concert reviews and titles of his original compositions: Announcing a third Knoxville appearance, this article makes several interesting claims: Prince Wilburn is said to represent the colored Bible Institute of Knoxville. Newspapers do mention a Bible institute in several cities, typically spanning about four days. I have found no mention of a "colored" Bible institute although it may have existed and have received charitable donations. The first paragraph of the Greensboro [NC] Record's August 9 Wilburn concert announcement also says Wilburn is touring to raise funds for Knoxville's colored Bible Institute. However, the second paragraph states, "He is now traveling under the auspices of the board of trustees of the Universal Bible institute of Knoxville, which is engaged in the construction of a college plant to cost $75,000." My search of Knoxville newspapers found nothing about a Universal Bible Institute, leaving me wondering if these claims were false and if the proceeds went directly into Wilburn's pocket. Prince Wilburn is said to be "visiting America." Like the previous article's claim that he was on his first American tour, these words must be aimed at convincing people that they have the opportunity to see a real, live West African fresh from the Gold Coast. As Wilburn expands his travels in 1931, his story evolves, giving him more time in the U.S. or other parts of the world.

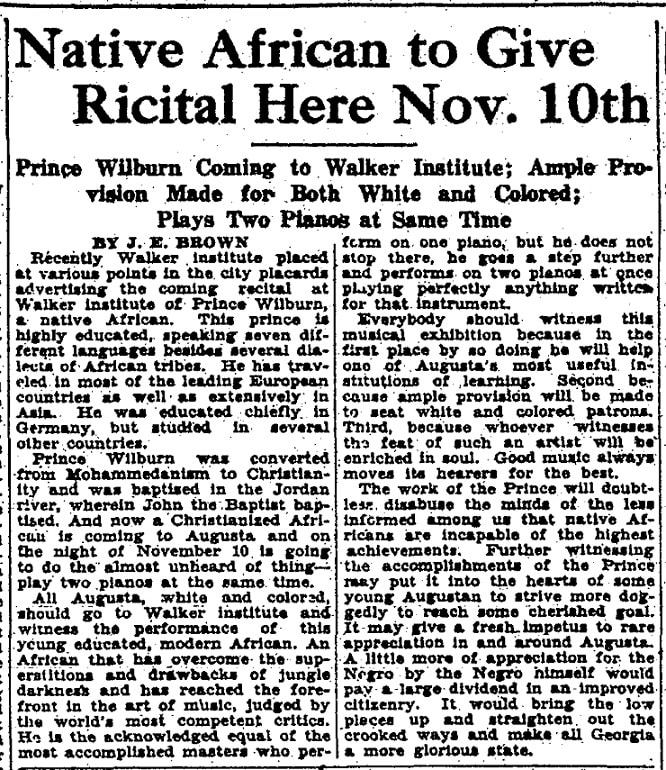

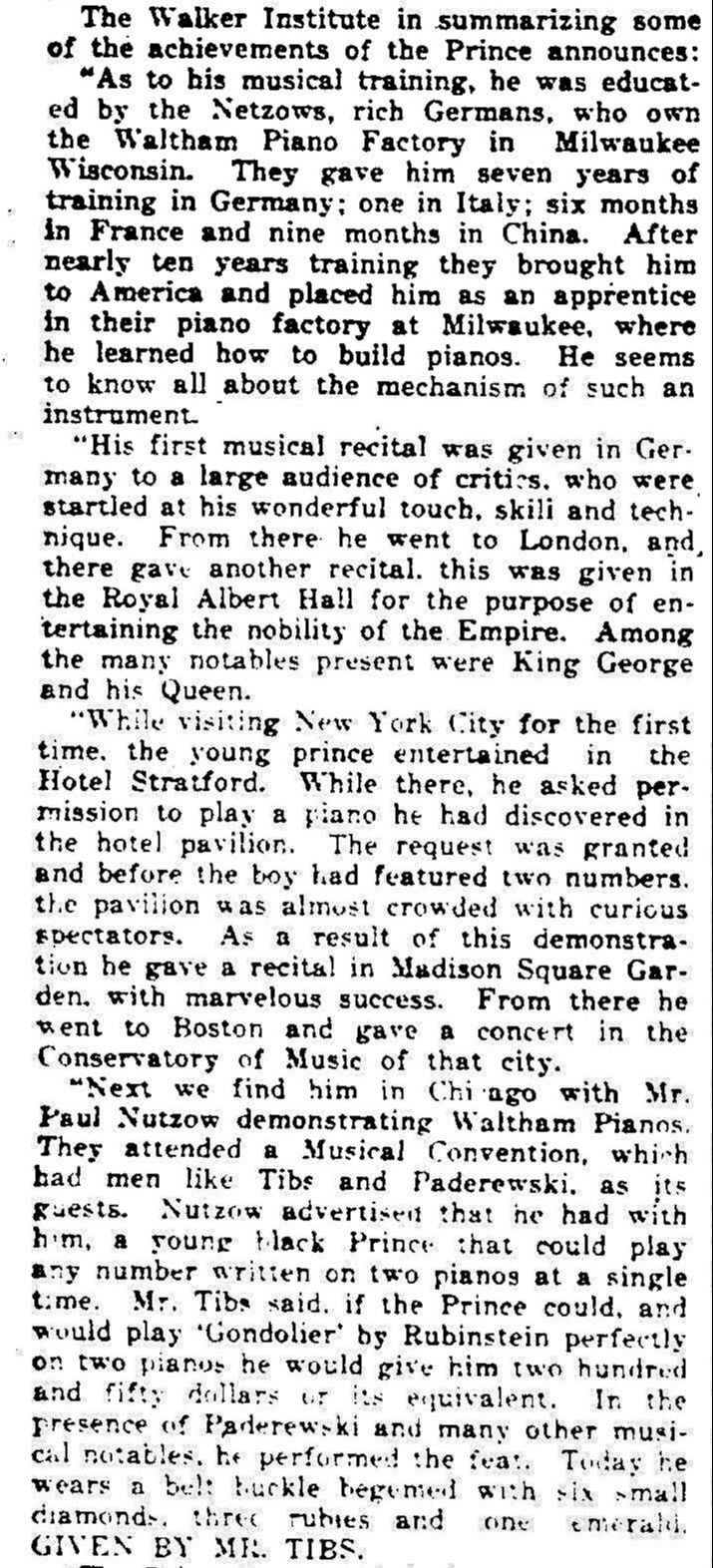

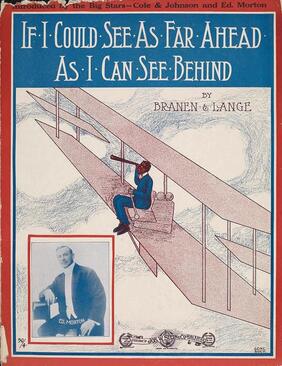

Since most of DeBar's fraudulent activities occurred during the late 1800s to very early 1900s, we might guess that Chester Wilburn, born in 1891, was too young to know her story, but he was not. Detailed articles about DeBar's long-term con game appeared in newspapers at least as late as 1929, a year before Wilburn seems to have become the Crown Prince of the Gold Coast. Comparing himself favorably to DeBar in what must have been a fake review may have been Wilburn's way of saying he could outdo her. Although the Chicago Tribune review contains no specific traceable details other than the review, itself, it does not strike me as the work of a professional music critic. Look at the final sentence: "Prince Wilburn, the two piano artist, is this and more." This what? He cannot be "a cultured ear" or "modern music." He cannot be an overtone, a nuance, or a modulation. The paragraph sounds as though some words and phrases have been picked up from another source or other sources and strung together. I have seen similar words and phrases in advertisements for pianos or various makes and models of early record machines. The article further claims that Wilburn has composed "stage diversions." Searching copyright catalogues from 1910-1930, I found no copyrights containing the names Chester Wilburn or C. W. Wilburn. Of course, he could have composed music without copyrighting it, but a stage show selection--at least, one anyone had heard of--would have been copyrighted along with other music from the show. I have not identified "The Storm" as a "stage diversion." However, "The Gondolier" might refer to Gilbert and Sullivan's The Gondoliers, which, along with other Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, was a frequent road or community production. As evidenced by newspapers, selections from The Gondoliers also aired on the radio. Another popular possibility could be Ethelbert Nevin's "The Gondoliers," no. 2 in his piano suite A Day in Venice, op. 25, especially since Wilburn also performed "The Rosary," which could have been Nevin's. However, referred to as a "stage diversion," his plan to include something he called "The Gondoliers" seems more likely to have been from Gilbert and Sullivan. This thinking, of course, assumes Wilburn's "stage diversions" were actual stage/show tunes. In my hunt, I came across another possibility--Friedrich Burgmüller’s 18 Études, op, 109, including "L'Orage ("The Storm") and "Refrain du Gondolier" ("The Song of the Goldolier"). Burgmüller’s various collections of études have been used by generations of piano students, some of whom are now posting their performances on YouTube. Perhaps someone had been providing Wilburn with a music education, or perhaps he had decided a ragtime repertoire would no longer suffice, especially if his target audiences were church congregations. In what appears to be his first year as a prince, Chester Wilburn also performed in Coeburn, Virgina and Greensboro, North Carolina. In 1931, he started up again by mid-February, touring North and South Carolina and Georgia through the early part of 1932. That would prove to be his busiest year and one in which he grew more creative. Although African American churches were the most common sites for Prince Wilburn's performances, his venues included schools, fairs, clubs, and even and old court house. Describing his appearance in a school auditorium, the next news clipping from North Carolina also demonstrates how Wilburn's story began to grow and change: Most of the biographical elements are laughable. Wilburn was not content to be a normal heir to the throne--an eldest son. Instead, he had to be the youngest, perhaps setting the Gold Coast apart from the rest of the world as the only place to make the youngest son first in line of succession. Appearing for African American audiences, he could not present himself as snobbish royalty. Instead, he posed as a supporter of democracy, banished by his father for his radical views. The fictitious location of the conservatory where Wilburn allegedly studied--Rhapsody, Germany--is so outlandish that it is difficult to believe anyone could have fallen for it. His conversion on Mount Calvary and baptism in the River Jordan are clearly designed to appeal to religious audiences, and although the current venue is a school auditorium, African American churches sponsored the concert and would benefit from the revenue. Wilburn or his manager, said to be Rev. William B. Harrington of Concord, North Carolina, made an egregious error in the early days of Wilburn's travels by identifying Monrovia, capital of Liberia, as part of the African Gold Coast. Never colonized by Europeans, Liberia was purchased (some say by force) by the American Colonization Society as a location for resettling freed slaves. Named for James Monroe, U. S. President at the time, Monrovia became the capital of Liberia, meaning "free land" or "free country." Monrovia was not a kingdom. Despite this early error, we have already seen Wilburn name Aqua [Accra, Ghana] as his birthplace when he registered for the WWII draft in 1942. Wilburn's story, as it first appeared in newspapers, was eventually revised, probably to correct this this geographical and historical error. When announcing a Wilburn concert in Greensboro, North Carolina, the August 9, 1930 Greensboro Record supplements the information about Rev. Harrington. Although supposedly from Concord, North Carolina, Harrington is said to have graduated from Wake Forest and to live in Louisville, Kentucky. If Harrington graduated from Wake Forest, he was white; university trustees voted to end segregation in late April, 1962. Harrington has proven difficult to pin down. I have found several Rev. William B. Harrington's, one sometimes called a "farmer minister," but none appear connected to Wilburn. Was Wilburn's manager really a minister named William B. Harrington, who tried to do good by arranging concerts for a converted African Prince and largely African American audiences, with seats available for music-loving whites? Did he believe Chester Wilburn's stories and pass them along in promotional materials? Or, perhaps, was he the mastermind behind some or all of Wilburn's fraudulent identity? Reverend William B. Harrington would soon vanish; news-papers do not mention him after summer 1931. The story of Wilburn's "bejeweled belt" would also later change, becoming less credible. There could be an ounce of truth to the comment about the Chicago piano manufacturer. We will look at that story more closely soon. Another North Carolina article adds comedian and lecturer to Wilburn's list of talents, mentions performances for European royalty, and assigns him a title to rival Joplin's. Wilburn becomes the Prince of Music, more inclusive than King of Ragtime. Much like the claim that Wilburn had composed popular "stage diversions," readers are now led to believe that Wilburn had written many other popular titles they would probably recognize. A late 1931 article from Augusta, Georgia, begins much like most other articles but changes direction in the third paragraph. Rather than focusing on Wilburn's talents or biographical details, it motivates the city's black citizens to attend the concert, encouraging them to see the obstacles Wilburn has overcome and the heights he has achieved, inspiring them to set and achieve their own goals, and suggesting how Wilburn's example could increase self-esteem and improve society. Two days before the Augusta's Walker Institute concert, the Chronicle quotes details from promotional material, revealing the extent to which someone has gone to create and convey the story. Although we have seen a previous mention of a Chicago piano manufacturer who educated Wilburn in American and later sent him to the conservatory in Rhapsody, Germany, we now learn the identity of the manufacturer. The promotional materials also tell tales of European, New York City, and Chicago performances, presenting a new story about Wilburn's "bejeweled belt," previously said to contain royal diamonds from the Gold Coast. This account seems to indicate that Wilburn did not come to the U. S. until after his education in Europe and China. His international education is as likely to be true as his royal birth in Monrovia, the Gold Coast. Some of the information is based on facts. Charles F. Netzow (not Nutzow), a German immigrant, founded a Milwaukee piano company that manufactured Netzow pianos. Eventually, the Netzow family took over the Waltham Piano Company and began manufacturing Waltham pianos along side their Netzow brand. Assuming the Charlotte News may have been working from the same promotional materials as the Augusta Chronicle, perhaps the Charlotte News reporter made an error when it previously connected Wilburn's story to a Chicago piano manufacturer rather than a Milwaukee manufacturer, based on the story about the Chicago convention.

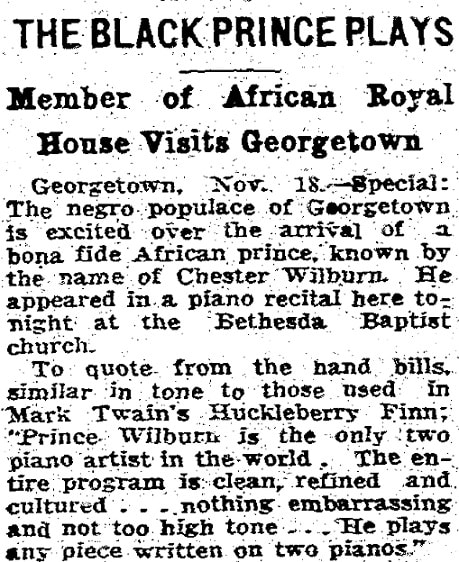

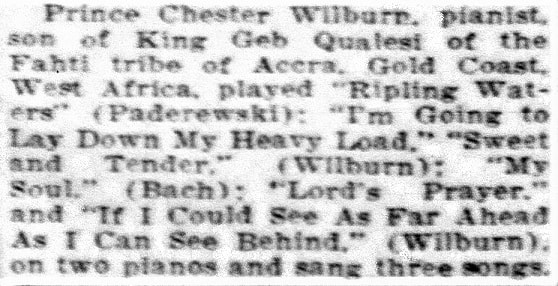

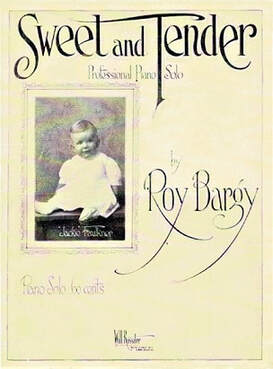

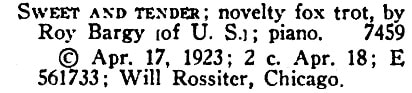

A variety of items in Presto and The Music Trade Review also report Waltham Piano Company's participation in the annual National Music Trade Convention in Chicago, and this must have been the convention at which Wilburn claimed to have won the jewels he later wore on his belt. As general manager and then president, Paul Netzow attended the conventions to display and promote Waltham's latest models. Although part of the story is true, the challenge is separating truth from fiction. We can rule out the Netzow's philanthropy--their providing Wilburn with nearly ten years of international music education. Wilburn's story seems to require their having met Wilburn outside of the U.S.--perhaps in Germany where he claims to have begun his musical education. Why would they have invested so much in a young African prodigy, only to bring him to the U. S. and make him a piano factory apprentice rather than a concert pianist? The Stratford Hotel story also poses problems. I have not found a Stratford Hotel in New York City, but possibly Wilburn meant the Stratford Arms. If so, it was not built until 1928, and the information provided by Wilburn or his manager indicates that Wilburn was a boy after the ten years of international study. By the time the hotel was built, Wilburn would have been about 37, hardly a boy. The story about performing at Madison Square Garden and in Boston as a boy are definitely phony. If the Netzows did not meet Wilburn in Africa or Europe and fund his education, Paul Netzow still may have met Wilburn. During Chester Wilburn's years in Chicago, Waltham Piano Company of Milwaukee occasionally ran job listings in Chicago papers for positions such as piano finisher or regulator, and Wilburn might have worked for Netzow in some capacity although I have found nothing to verify that he did so or ever lived in Milwaukee. I did, however, find one hint that some Netzow instruments may have been manufactured in Chicago, making it possible for Wilburn to have worked for the family there rather than in Milwaukee. That hint is a classified ad in The Pantagraph (Bloomington, IL, June 14, 2014) for a reed organ said to have been made by the Netzow Company in Chicago. Photos of Netzow reed organs I have seen online are clearly marked "Milwaukee" immediately above the keyboard, so the instrument on sale may have been as clearly marked "Chicago." A job for the Netzows in Chicago might explain the nature of Wilburn's factory job at the time of the 1920 census. The Netzows also owned a chain of stores in other states and cities, so Wilburn might have worked at one of the stores, for example as a piano tuner. As a showy pianist, he might have been recruited to demonstrate the new models. His two piano performance would have attracted attention. Under such hypothetical circumstances, Wilburn might also have traveled with Netzow to demonstrate pianos in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, providing a modicum of truth to Wilburn's stories. When reading the convention incident, I did not know a pianist named Tibs, and after some research found only one man who fit the time period--Leroy Tibbs, a blues pianist. Listen to pianist Leroy Tibbs and singer Ethel Ridley perform Alabama Bound Blues (1923). Paderewski and Tibbs might have arrived at Paul Netzow's Waltham exhibit at roughly the same time while Chester Wilburn was demonstrating new models and performing his two piano stunt, and Tibbs' might have challenged Wilburn. Although this seems unlikely, it is not impossible. The described nature of the challenge raises major doubts, though. During Wilburn's early Knoxville concerts, "The Gondolier" was mentioned as a "stage diversion" composed by Wilburn, a claim already disputed. Now less than a year and a half later, we are told that a man, who most likely was a black blues pianist, had challenged Wilburn to play Rubinstein's "Gondolier"--a piece Rubinstein does not appear to have written--and subsequently rewarded him with diamonds, emeralds, and a ruby when he met the challenge. Wilburn must have liked the word gondolier. Although the Tibs/Tibbs-Paderewski story cannot have much truth to it, if any, it became the regularly published version of his belt story, replacing the royal crown jewels version. One would think many people must have doubted Wilburn's stories, but only rarely did any hints of skepticism appear, such as the following writer's clever comparison of Wilburn's handbills to those in Huckleberry Finn: Reporting Wilburn's visit to Georgetown, South Carolina, about 60 miles up the coast from Charleston, the writer alludes to the section of Huckleberry Finn in which Huck and Jim join up with two charlatans, the Duke and the King. The younger of the pair claims to be the lineal descendant of the legitimate Duke of Bridgewater, who had been cheated out of his title as an infant. The elder claims to be the rightful King of France, "Looy the seventeen, son of Looy the sixteen and Marry Antonette." As the two frauds travel downriver with Huck and Jim on the raft, the Duke and the King rehearse for a Shakespearean production, get handbills printed at a stop along the way, and upon arrival in Arkansas distribute the handbills, proclaiming themselves famous tragedians David Garrick the younger and Edmund Kean the elder, and performing three farcical scenes from Shakespeare, including a mangled version of Hamlet's soliloquy. At the end of Chapter XIX, Huck confessed, "It didn't take me long to make up my mind that these liars warn't no kings nor dukes, at all but just low-down humbugs and frauds . . . If they wanted us to call them kings and dukes I had no objections." Perhaps like Huck, Wilburn's audiences didn't care. In March 1932, Wilburn performed in Charleston, planning to play a surprising thirty-one numbers despite sharing the program with a Nigerian lecturer. His story also continued growing as he adopted an African name. The identification of the Nigerian's home as Logos rather than Lagos may be a simple error but could also indicate that he was another scam artist. Whatever the case, he was not an addition to Wilburn's act because this is the only time I came across Dr. Deinyi. A surname search of the Ancestry website turned up a sizable number of Labulas, many in international records from the Philippines, Mexico, or Slovakia and a few designating their birthplaces as Spain, Argentina, or Hungary. None appeared to be African. The oddest result came, not from Ancestry, but from a Google search that turned up a Bellevue, Washington restaurant named La Bu La. The restaurant website provided the Chinese characters for "La" and "Bu La," explaining that the words mean "spicy" and "not spicy." When I copied and pasted the characters into an email and sent them to a former Chinese exchange student who had lived with my family, he replied that "la bu la" is used as a question asking diners or guests how they prefer their food. Qualesi was also difficult to pin down. The one Qualesi on Ancestry had the last name Hernandez, but I found many variations such as Qulesi, Qualsey, Qualis, Quales, Qualus--mostly in the South, some identified as black and some as white. My searches were little or no help in explaining Chester Wilburn's African name. In mid-March 1932, Prince Wilburn disappeared from newspapers, not to reappear until April 23, 1934, in Covington, Kentucky. That reappearance was not one of his typical venues. Rather than being the main show, he was part of Heaven Bound, a musical drama depicting "the temptations that the pilgrim encounters on his way through life." Sponsored by the white Trinity Episcopal Church, the show was performed by a black cast directed by a man from the First Baptist Church: The cast includes the rich man, the hypocrite, the thoughtless flapper, the man about town, the lost brother, the true believer, children’s chorus, the heavenly choir, the Kentucky jubilee radio singers, Prince Wilburn, of the gold coast, Africa, and the pilgrims. (The Kentucky Post [Covington, KY], April 24, 1934, p. 4) Most likely, Wilburn was the accompanist. Because Wilburn did not appear again for more than a year and because the Covington musical drama was a, one-time, local church production, I began wondering if he might have been living in the area. Looking at a map, I saw that Covington is directly across the river from Cincinnati. When I checked the Cincinnati directory, I found an entry that is probably Chester Wilburn, who may have needed money. Of course, I cannot be sure what he was doing; however, if this is Chester and if he has worked for the Netzows in Chicago or Milwaukee, he might have been working at another piano factory. Cincinnati was home to Baldwin and Wurlitzer. The fact that he appeared to be living under the name of Prince C. Wilburn explains why I missed him earlier when searching for Chester Wilburn. It may also explain his use of the name Prince when he married Lillian Hunt three years later. In 1934, Wilburn performed in Michigan, most often in Detroit, but I have not been able to find any record of his living there. A large black family headed by Chester Ivory Wilburn did live in Benton Harbor, Michigan, and previously had lived in Arkansas and Missouri, but I have not been able to connect them to the musician Prince Chester Wilburn. Birth and death dates for the father and one son also named Chester do not match. When performing in Port Huron, Michigan, Prince Wilburn added a father's name and identified him as King of the Fahti tribe (correctly, Fanti or Fante), also finally changing their home from Monrovia to Accra--from the capital of Liberia to proper location in the Gold Coast. Although misspelled as "Aqua" on Wilburns WWII draft registration form, Accra now became the city of birth specified for the remainder of Wilburn's life. I do not know if Wilburn was aware that Geb was the ancient Egyptian god of the earth. Even if not, that part of his father's name seems consistent with Wilburn's deception. More interesting are some of the selections he performed that evening. "I'm Going to Lay Down My Heavy Load," often known as "By an' By, "comes as no surprise as a spiritual. "Lord's Prayer" and "My Soul" are impossible to identify Because the former had been set to music many times and the latter appears to be only two words used in many Bach pieces, rather than the full title of any. Paderewski's "Ripling [sic] Waters" also does not seem to exist, so Wilburn might have picked it up somewhere else. Since he previously claimed to have composed "stage diversions" called "The Storm" and "The Gondolier," both of which may have been stolen from Burgmüller’s 18 Études, op. 109, a possibility could be no. 5 in that collection of piano studies, with the English title "The Spring." Of course, this is highly speculative, but that music would fit the more descriptive title he claimed to have been Paderewski's. Most revealing are the two titles Wilburn supposedly composed. Quite likely, he was passing off other people's work as his own:

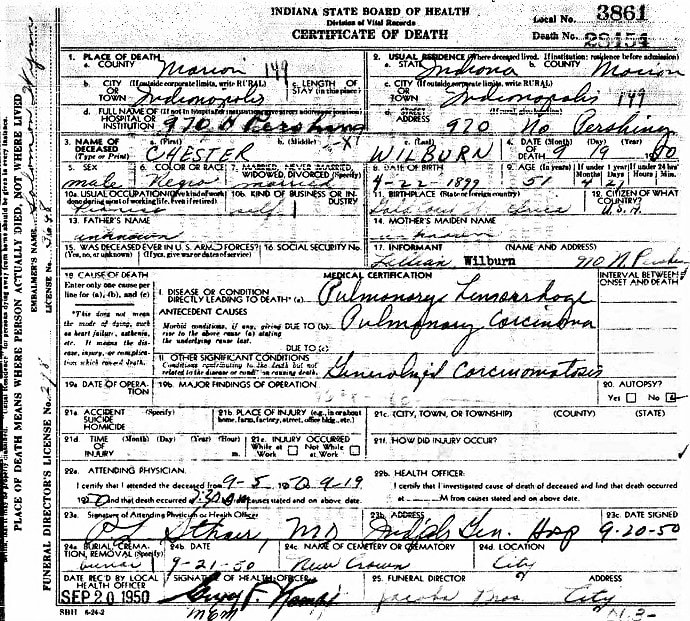

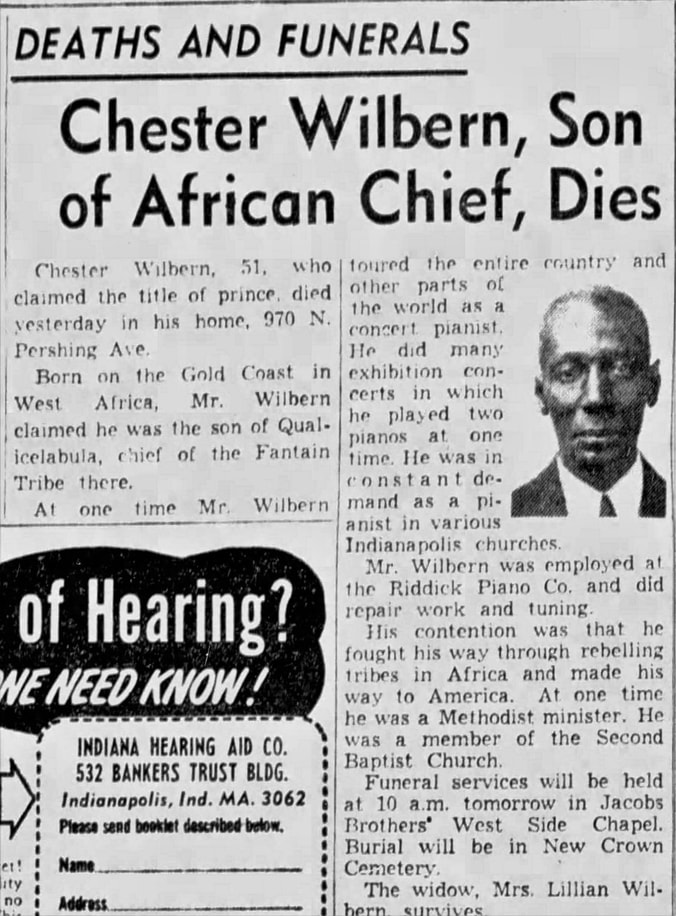

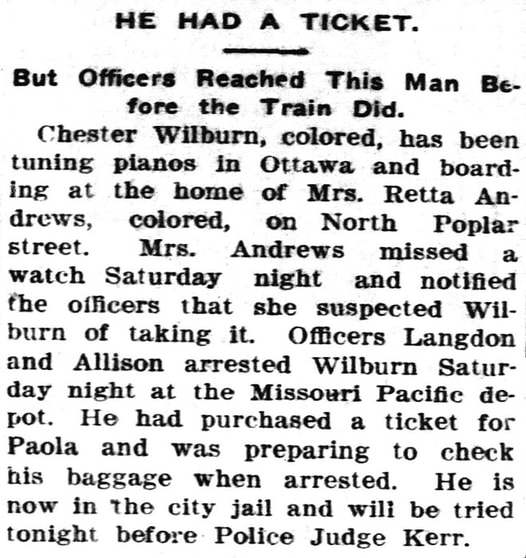

After a handful of Michigan venues in 1935, Wilburn made several 1936 appearances before marrying Lillian Hunt of Indianapolis in November. Photos of Wilburn accompanied the announcements of two appearances, the first in Danville, Kentucky and the other in South Bend, Indiana. I will save the Danville photo for later when it serves a better purpose. For now, only the South Bend article adds new information as well as a photo: The South Bend Tribune sounds skeptical of Wilburn's story, which has grown more outlandish with the addition of his father's advanced age. However, if the youngest son inherited the throne, many brothers could have preceded Prince Qualesi Labula. By the time he reached Evansville, Indiana two months later, Wilburn had further inflated his education. This is the first time I have come across a lecture title, but not the first time Wilburn has spoken. When his lectures were mentioned in the past, he typically talked about his life and experiences in Africa, which likely included his conversion on Mount Calvary and baptism in the Jordan River. Perhaps this could have been a similar lecture. After Wilburn married Lilian Hunt, he must have ended his out-of-state performances. Instead, he continued his concerts and occasional lectures in Indianapolis, traveling now and then to such places as Noblesville, Lafayette, Evansville, Franklin, and Kokomo, anywhere from 25 miles to roughly 175 from home. Although the 1940 census identifies him as a professor of music, we have also seen him working in a GMC plant in 1945 and as a carpenter in 1949 Cincinnati city directories. In May 1945, while he was probably working at the GMC plant, Prince Wilburn's story expanded again. He became Reverend Prince Wilburn, who had studied languages in Egypt and Europe. Wilburn may have classified any religious song as a spiritual. Although I have not been able to trace the mockingbird title, the others are gospel songs, a musical setting of Biblical verse, and a Christian hymn growing out of the last days of the British slave trade. As for "the Chinese language, 'Hopping John,'" I can picture the ragtime era sheet music cover art, yet I have not found a "coon song" or rag by that title. Whatever music Wilburn performed and perhaps sang in Chinese, was most likely neither Chinese, nor sung is any authentic Chinese dialect unless he learned it from a Chinese immigrant. Hopping John is the name of a common soul food throughout the South and prepared by many white families, including mine, on New Year's Eve or New Year's Day. According to Southern tradition, eating Hopping (or Hoppin') John for the new year brings good luck. Chester Wilburn may have enjoyed this joke on the Hoosiers, but perhaps Southern blacks who had moved north during the Great Migration had their own laugh explaining Hopping John, as they knew it, to the Oxford-educated West African, whom they believed thought it no more than a Chinese song. January 25, 1948, may have been Prince Chester Wilburn's last hurrah; at least, it was the last performance I have found. He had lived in Indianapolis for well over a decade, yet the advertisement announced that he was "in the city." Most likely, these words were added to persuade people not to miss a rare opportunity. Chester Wilburn, self-employed pianist, died on September 19, 1950, of lung cancer. Upon his death, Lilian reported that he was born in the Gold Coast of West Africa on April 22, 1899, parents' names unknown and royal title ignored. When publishing his obituary, the Indianapolis News appears to have questioned some of the information, or perhaps Lillian did as she provided information. The words "claimed" and "his contention was that" tell us as much. If all based on Lillian's memory, her memory may have been failing, for Chester is said to have been the son of "Qualicelabula," Chief of the Fantain tribe rather than to have been Prince Qualesi Labula, son of Geb Qualesi, King of the Fanti tribe. If Chester Wilburn did not tour "the entire country and other parts of the world" as reported, he toured portions of the Midwest and Southeast. If he toured other parts of the world, he likely did so in his imagination or wildest dreams. True to form, we have one final surprise in his obituary--his contention that he fought his way way through rebelling African tribes and made his way to America. This version of his story contradicts the version in which the wealthy German Netzow family educated him in Europe before bringing him to the U.S. as an apprentice in their piano factory. If Chester Wilburn ever worked as a Methodist minister, I haven't seen any evidence other than a mention of Rev. Wilburn in one Indianapolis News article. Whether he was still working as a carpenter as in the 1949 Indianapolis directory, we are not told, but we learn that he was working in the piano industry as a tuner and repairer. Born on April 22, 1891, Chester Wilburn was 59, not 51. His widow Lillian lived another seven years and ten days, dying on September 29, 1957. Her age at death was recorded as 75. According to her age in the 1910 census, she would have been 78. Answering Several Remaining QuestionsWere Chester Wilburn and C. W. Wilburn, who posed as Scott Joplin, the same man? That is the big question. After discovering Chester Wilburn in 1911 Oklahoma City, the place from which C. W. Wilburn reportedly came to Southeast Kansas and after tracking what appears to be the same Chester Wilburn from place to place, I returned to historic Kansas newspapers to see if I could find anything new that had not turned up in searches for Scott Joplin or C. W. Wilburn. The Hutchinson and Arkansas City articles posted in Ragtimers Club spoke only of Scott Joplin, never mentioning Wilburn. The Hutchinson article identified Joplin as "king of all ragtime players, writer of the Maple Leaf Rag and many other popular rags" and announced that he was visiting friends in town for a few days. Other than the suspicious timing of such a trip while Joplin was working on Treemonisha, the only suspicious element was the mention of Joplin's being from Chicago. The Arkansas City articles seemed to rule out Joplin. Joplin was not from Cairo, Illinois. He was not soon to make an "extended visit" to New York" because he had lived there for about six years. He would not have included a "physical exercise stunt lasting one hour" in his performance. I needed to look at Hutchinson and Arkansas City more closely. Two small Wilburn items appeared in Hutchinson, one saying that C. W. Wilburn of Arlington was one of the out-of-town visitors that day, the other that C. Wilburn from Arlington was conducting business in Hutchinson. Despite the promising sound, I doubted that a black Wilburn would have been accorded such notice for so little reason. A check of public records on the Ancestry site revealed that Arlington's C. W. Wilburn was probably Charles W. Walborn, a white Arlington merchant with a general store. I found no C. W. Wilburn in Arlington. Another look at Arkansas City papers proved more successful although it raised new questions. By limiting the search to May 1913 and searching for "Wilburn," I discovered a puzzling article: Had Joplin assisted Professor Wilburn with the entertainment? Somehow this doesn't ring true. The article plainly states that Wilburn gave the entertainment. Might someone else have posed as Joplin? Or is this another case of "Wilburn, also known as Scott Joplin" with the names used interchangeably? No mention is made of what Wilburn did to entertain, only of Joplin. A look back at the Arkansas City articles previously posted in Facebook's Ragtimers Club supports the theory that Wilburn was Joplin during the time in Southeast Kansas. On May 14, the Arkansas City Daily News had reported, "Scott Joplin . . . will give a grand musical entertainment at the colored Masonic Hall tonight," thus indicating Joplin, not Wilburn, was responsible for the show. The next day, the Daily News reiterates that information, "The Entertainment given by Scott Joplin at the colored Masonic hall last night was very pleasing and quite well attended." The Daily News ignores Wilburn's role or participation although the Daily Traveler credits Wilburn with planning and offering the show. The Daily Traveler never mentions Wilburn or Joplin again after commenting on the previous night's show, but a week later, the Daily News announces Joplin's departure for New York: This announcement is consistent with the Daily News' use of only Joplin's name. If this were Joplin, he would have been returning to New York to launch a rehearsal and then a performance--hopefully, performances--of Treemonisha. Could he also have been planning to work for an obscure piano roll company? Although I have not been able to verify the existence of Hanasan, he may have needed to earn money to fund the production. Even if that were the case, why would Joplin have given the impression he was going for an extended stay to make piano rolls when he could have voiced his enthusiasm about his return to his home in New York for his impending opera--his achievement of a lifetime? He did not yet know his efforts would fail. Although the Arkansas City press does not mention Wilburn after May 15, the May 23 Topeka Plain Dealer and May 24 Kansas City, Kansas, National Review carried identical items in their "Arkansas City" news column: At first, I assumed this item referred to a Wednesday, May 21 Arkansas City event I had not located. Since a local paper would probably have provided the news to the Topeka and Kansas City, Kansas papers, I read through Arkansas City papers between May 20 and May 22, looking for Wilburn's musical and drill at the Knights of Pythias hall. Neither paper mentioned such an event. With little knowledge of Masons and Knights of Pythias, I turned to Google and discovered the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library website, which indicates that Knights of Pythias members are Masons. With that knowledge, we can conclude that "last Wednesday" refers, not to a separate May 20 performance, but to the May 14 performance--the Wednesday of the past week. Furthermore, if Wilburn and Joplin were the same person, Wilburn could not have performed on the evening of May 21. Joplin had already left town for his so-called extended visit to New York. Wilburn would have been on the train with him, wherever it was headed. That destination appears not to have been New York. Within a month after leaving Arkansas City, Chester Wilburn made the news in Ottawa, Kansas-- roughly half way between Southeast Kansas where C. W./Professor Wilburn had performed and St. Joseph, Missouri, where Chester Wilburn later tuned pianos. As in the 1915 and 1916 St. Joseph, Missouri directories, Chester Wilburn was tuning pianos. As was the case with C. W. Wilburn in 1913 Fort Scott, Chester Wilburn was in trouble with the law. Chester Wilburn tried to skip town much as C. W. Wilburn had done in Fort Scott, forfeiting his bond. Unlike C. W., Chester was held in jail. What happened after Wilburn's release is even more revealing than his resemblance to scalawag C.W. Wilburn: As Ed Berlin documents in King of Ragtime, citing several articles from the Indianapolis Freeman and New York Age beginning June 14, Scott Joplin was in New York rehearsing Treemonisha and far too busy to entertain at a picnic supper in distant Ottawa, Kansas. The two sources closest in time appear below: The so-called Scott Joplin performing in Ottawa, Kansas, on June 27, 1913, must have been Chester Wilburn. With strong evidence pointing to C. W. Wilburn's fraudulent impersonation of Scott Joplin in Southeast Kansas and Chester Wilburn's in Ottawa, Kansas, and with the likelihood that these two were the same man who posed as the African Prince of Music across many states in the Midwest and Southeast during the 1930s and '40s, I still could not help feeling some piece of the puzzle was missing. Little did I expect to find that missing piece in Iola, Kansas, where "C. W. Welburn, better known as Scott Joplin" first made his way from the Allen County Journal to Facebook's Ragtimers Club. Although newspapers.com attributes the county paper to LaHarpe, KS, where it originated, by 1913 the paper was published in nearby Iola. When I realized I had not searched Iola since reading the assortment of articles Ed Berlin and Bryan Cather had posted on Facebook, I discovered a second Iola paper--the Daily News and Evening Register. The search engine led to nothing useful, so I decided to read the paper starting on April 17, the day of the Allen County Journal item. On the second page, I discovered a physical description, allegedly of Scott Joplin. Knowing from the Allen County Journal that Joplin's Iola performances were scheduled for April 21-23, I continued reading and found one more item worth including: I knew I had found the missing piece of puzzle. This was not Scott Joplin. Joplin would have been 45 on April 17, 1913, hardly an age to be labeled a "musical prodigy." We may have no record of Joplin's height, build, and finger length and structure, but based on photos of Joplin and Chester Wilburn and on physical descriptions of Wilburn, the Daily Register and Evening News description fits Wilburn. In addition to the WWI and WWII draft registrations describing Chester Wilburn as tall and slender and as 6’ 2¼” and 155 pounds, at least two other newspapers contain helpful descriptions: This 1936 photo of Chester Wilburn in his turban shows his bony wrists and hands: Might Chester Wilburn also have appeared as tall, thin Professor Pushee in Ebony Film Company's 1918 Mercy, the Mummy Mumbled? Since his 1917 draft registration indicates that he acted for Ebony, he may well have been there during the filming. Although we first see Professor Pushee in his lab, the blondish wig is distracting. The resemblance may best be seen when the professor, dressed in suit and top hat, comes to see the mummy at approximately 3:40 in the video clip. Watch a portion of the film here. Unfortunately, when paused for closer examination, the images become too fuzzy to examine closely. I cannot be certain. The description fits Chester Wilburn, but C. W. Welburn/Wilburn is in town. Public records fail to reveal Chester Wilburn's middle name or initial. His World War II draft registration indicates that he does not have a middle name, yet several facts point to Chester Wilburn being C. W. Wilburn:

Chester and C. W. Wilburn must have been the same man. Final Thoughts For whatever reason, Wilburn seems to have wanted or needed people to think he was someone famous--whether King of Ragtime, political prince, or Prince of Music. Perhaps fame rather than money motivated him.

The money he earned might have paid his board and gotten him from one place to another, and he also tuned pianos here and there, but several articles listing admission prices reveal he could not have done much more than scrape by. With ragtime's decline in popularity and possibly the difficulty or danger of posing long-term as a real person such as Joplin, Wilburn created a fictional persona appealing to mostly black church, school, and club audiences. This also allowed him to alter his personal history, glorifying it on a whim or revising it if a part of his story was discovered to conflict with geographical or historical fact and might increase the possibility of fraud charges. Although Joplin had visited Parsons and Fort Scott in 1904, most Southeast Kansans had probably never seen Joplin even if they recognized some of his music. If some people believed that Scott Joplin was the pseudonym of C. W. Wilburn, whatever fame Joplin had attained was Wilburn's fame. For a brief time, C. W. Wilburn was the King of Ragtime. Wilburn started over by adding a royal title to his name, becoming Prince Chester Wilburn and soon the Prince of Music. Even when he adopted the African name Qualesi Labula, every article included the name Chester Wilburn. Chester Wilburn was a liar, a fraud. Like Ann O'Delia Diss DeBar, baronness, countess, and princess, lecturer, spiritualist, magician, and actress, who conned a series of victims out of their life savings or inheritances, Wilburn has long been forgotten. We still do not know what became of his first and second wives, and although he gained a home by marrying Lillian, he remained with her until death and held down a variety of regular jobs to support her while she stayed home. Wilburn did not con his audiences out of more than a few cents, and for those pennies, he gave them music. It may not have been the music he announced it was. It may not have been his original work when he claimed it as his own. Chester Wilburn was a scoundrel. Yet his music entertained and made people happy. In some cases, it may have brought solace or renewed faith. As J. E. Brown wrote in the Augusta Chronicle, it may even have "disabused the minds of the less informed among us that native Africans are not capable of the highest achievements" and "put it into the hearts of some young Augustans [or other black Americans] to strive more doggedly to reach some cherished goal." Chester Wilburn was a rascal, but one worth knowing and remembering. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed