|

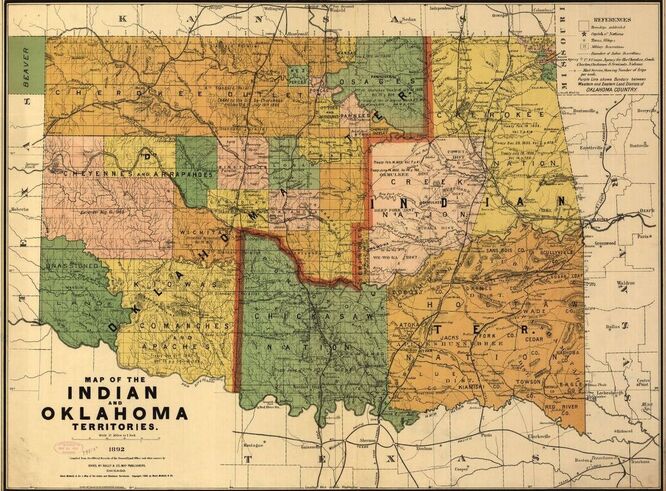

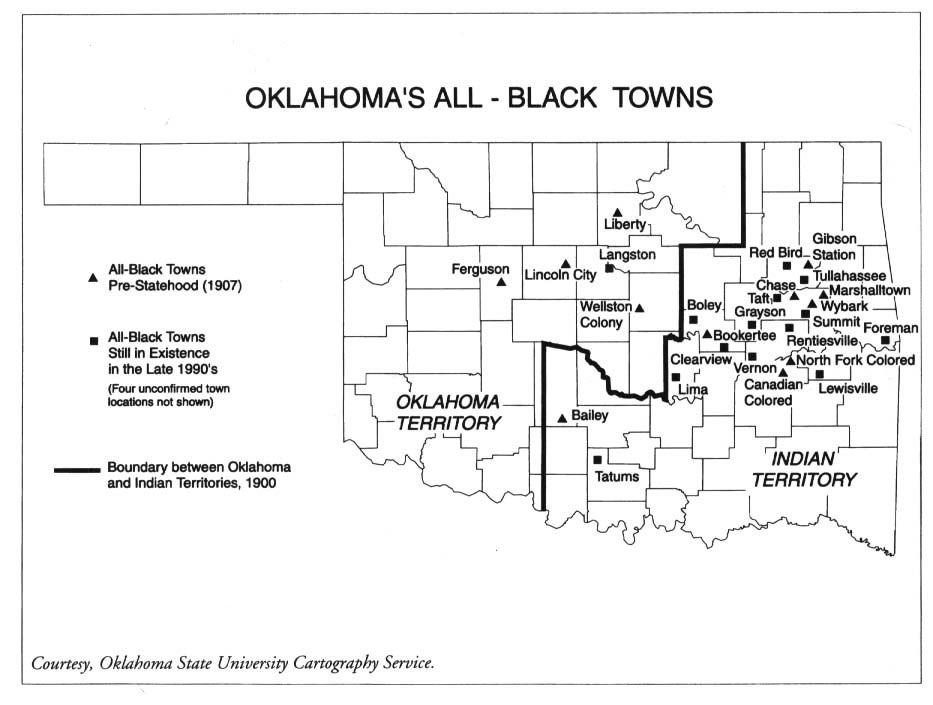

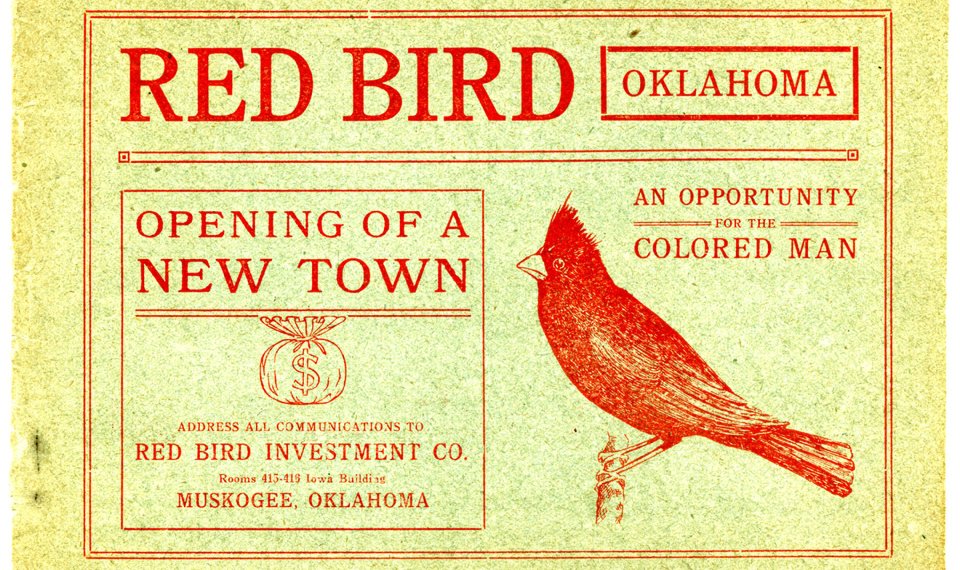

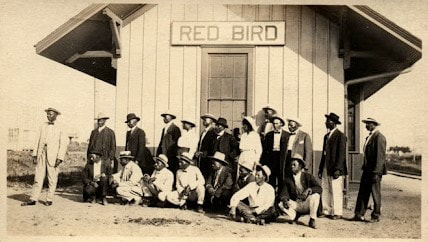

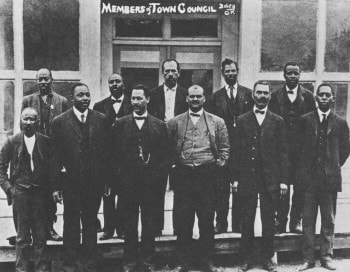

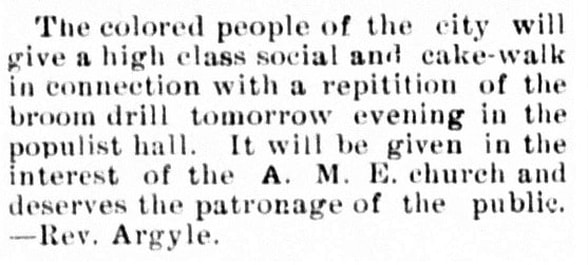

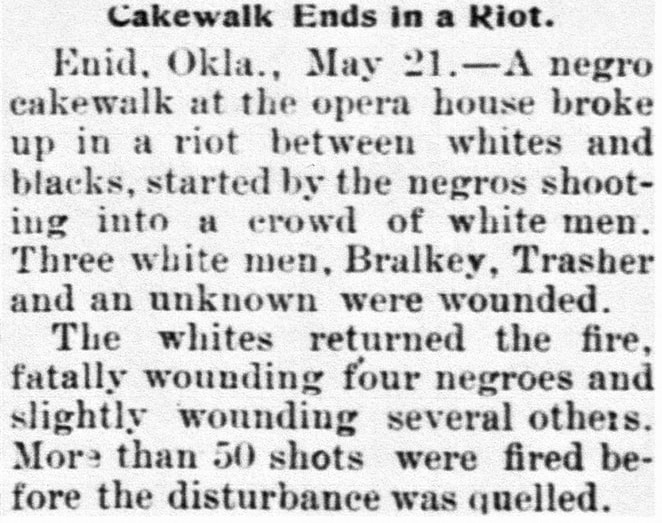

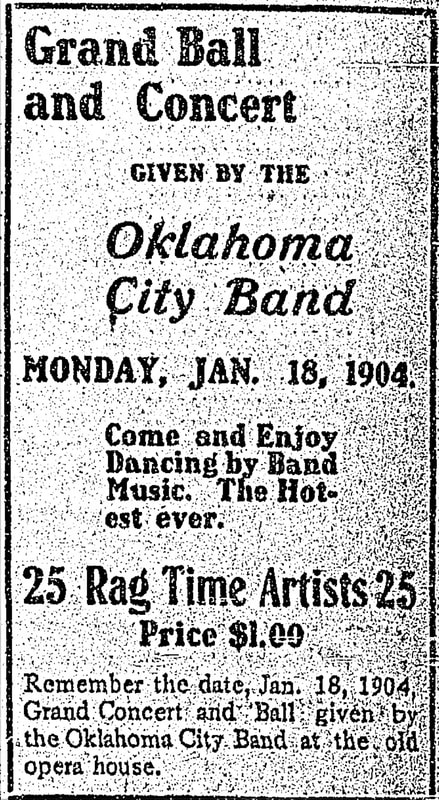

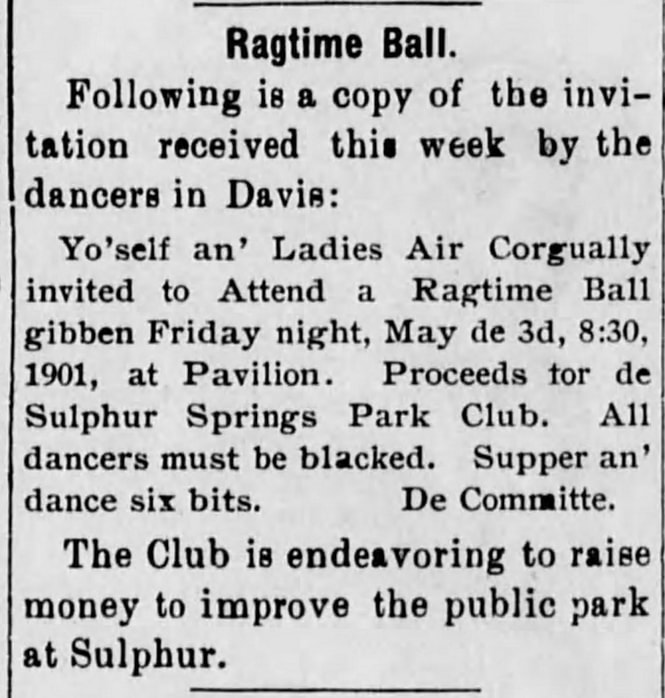

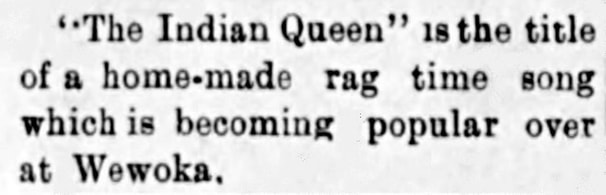

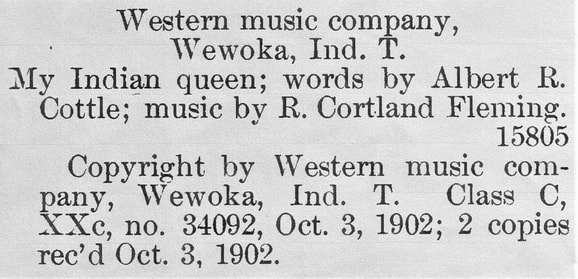

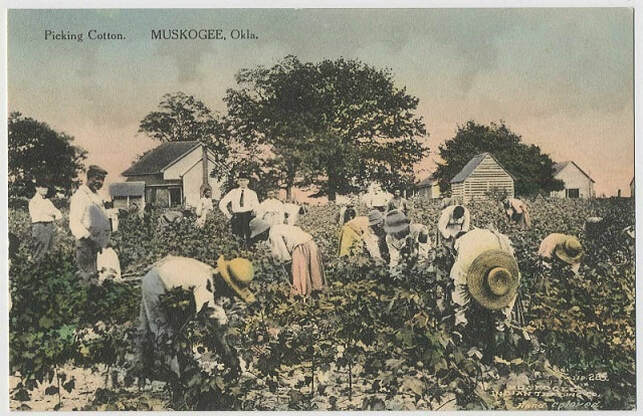

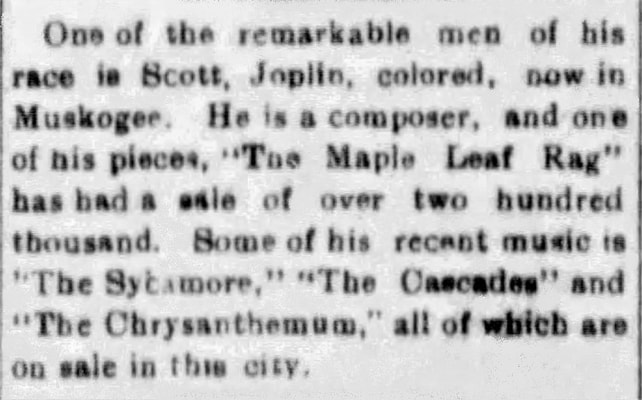

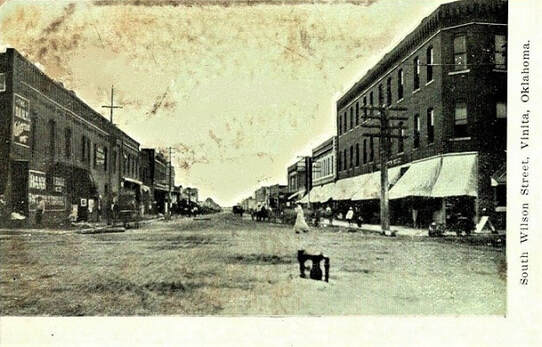

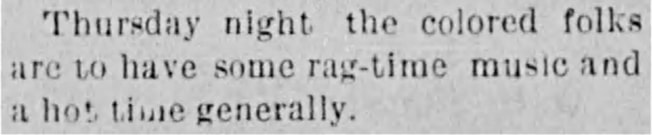

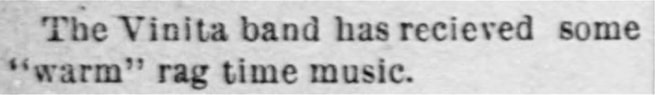

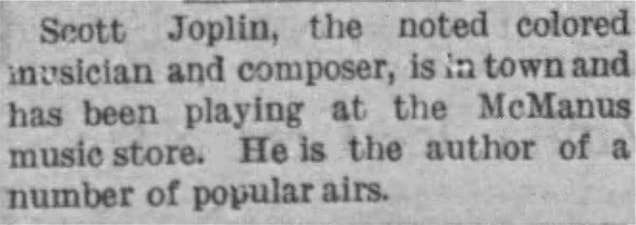

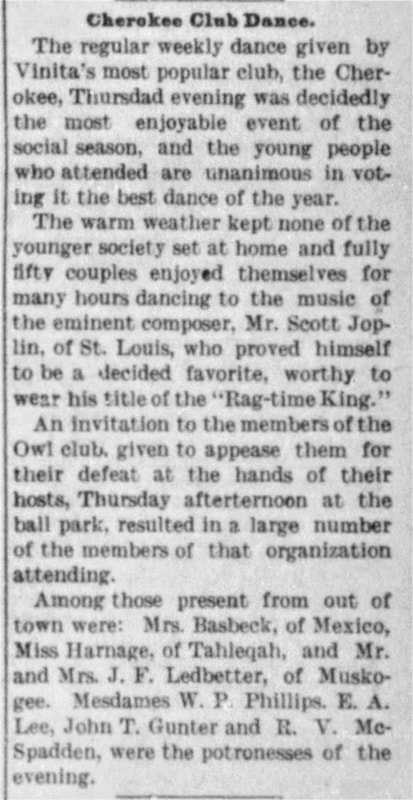

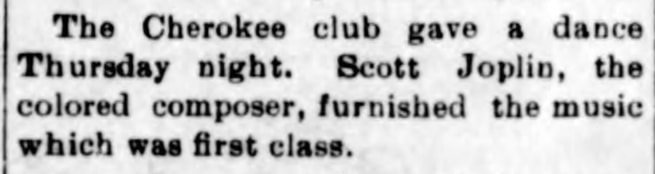

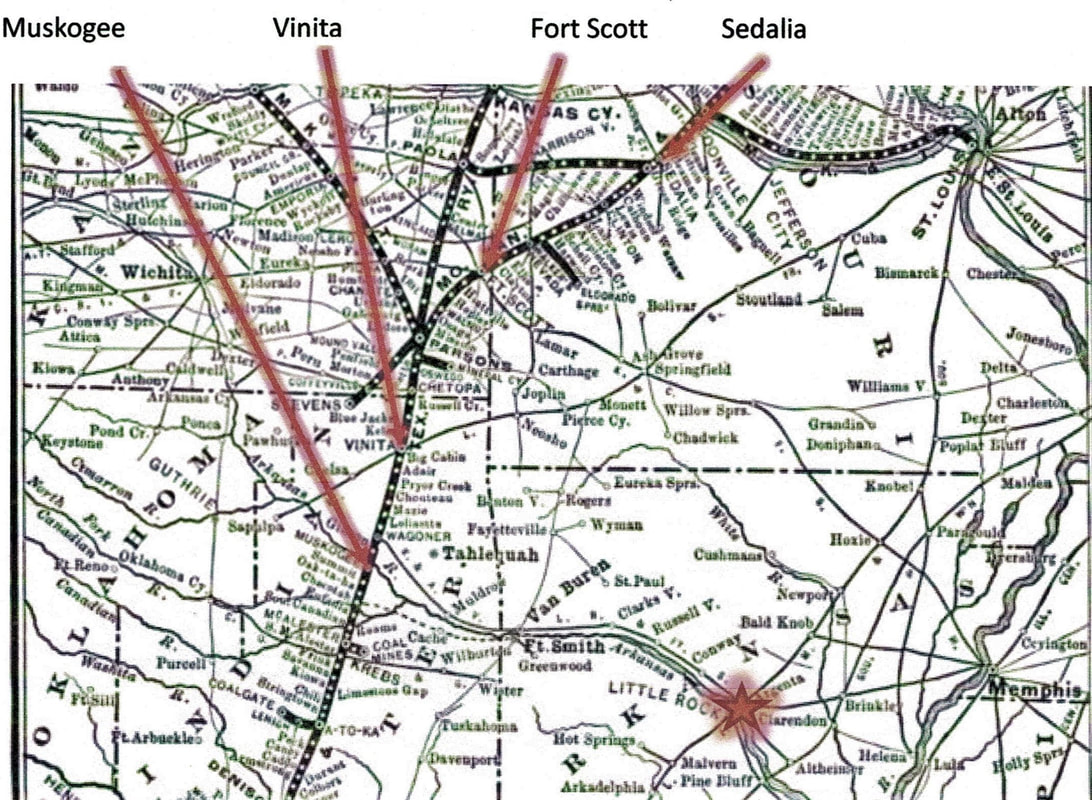

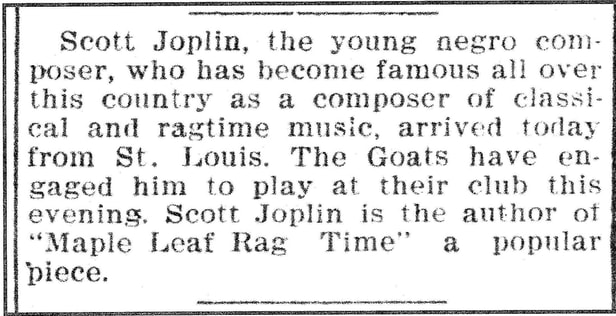

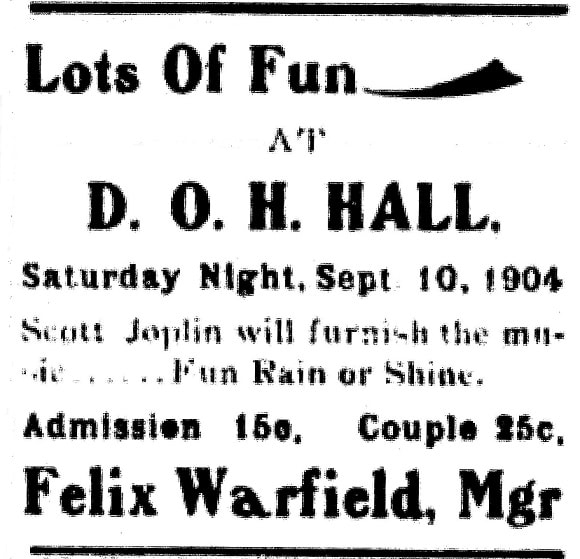

Scott Joplin's only identified trip through Oklahoma occurred roughly three years and four months before Oklahoma became the 46th state. When I began this project, I intended to provide brief historic and ragtime context for Joplin's visit and to document the visit itself--a simple, straightforward project. That remains a substantial portion of what appears below. Eventually, I realized that the tour through territorial Oklahoma extended beyond the borders, altering the established Joplin timeline. For that reason, I expanded my scope. As I pursued new ideas, I researched additional angles. New findings led back to an unanswered question Ed Berlin asks in King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era (2nd ed, 2016), and I will propose a possible answer to that question. Hopefully, the gradual evolution of this project has increased its significance. Anyone wishing to read only the Joplin findings may do so by scrolling down to "The Joplins Travel Through Indian Territory." Yes, Freddie Joplin must have accompanied her new husband on these travels. However, the earlier material will provide a broader understanding of what the Joplins would have experienced during their travels, and I will occasionally allude to that cultural background when discussing the Joplins. The Context: Territorial Oklahoma Native Americans and African American Slaves The United States government drove the Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee out of the Southeast during the early to mid-1830s, forcing them into Indian Territory, a portion of the Louisiana Purchase lands for which the government thought it had no other use. These tribes, which came to be known as the Five Civilized Tribes, had previously assimilated many of white society's ways as a means of proving they deserved to remain in the Southeast where they were. Many of these these people were mixed blood, a fact that would have aided cultural change. The Cherokees divided into two main factions--those signing a treaty agreeing to ceding all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi in exchange for $5 million and relocation aid and those opposing removal by every means possible, including eventual assassination of some of the leaders agreeing to removal. Led by Chief John Ross, who was only one-eighth Cherokee, those opposing removal used the Georgia court system and traveled to Washington, D. C., making friends in Congress. However, the discovery of gold in North Georgia and an increasing white demand for land spelled doom for Ross's efforts. The forced removal of Cherokees and other civilized tribes, on foot and horseback during winter, became known as the Trail of Tears. No one knows how many men, women, and children died before the tribes reached Indian Territory. The U. S. government downplayed the losses, placing the deaths at around 200, but other estimates are in the thousands. Like many other Southerners engaged in agriculture, some members of the Five Civilized Tribes owned slaves and brought them to Indian Territory. According to the National Museum of the American Indian, Choctaw Chief Greenwood LeFlore lived in a large Mississippi plantation home on 15, 000 acres and owned 400 slaves. Although not as wealthy as LeFlore, Cherokee Chief John Ross also owned slaves, who had worked his tobacco farm. Indian Territory, reserved for the Five Civilized Tribes, made up about half of territorial Oklahoma, roughly the eastern half. Oklahoma Territory, the western portion of today's state, was home to several indigenous tribes and, over time, became home to Midwest and Great Plains tribes forced to leave their homelands as the government separated Indians from the white population through similar removal processes. According to territorial records, by 1860, approximately 55,000 Native Americans, 8,400 African American slaves, and 3,000 whites lived in Indian Territory. That amounts to 82.83% Native American, 12.65% African American, and only 4.5% white. By 1900, with the influx of white settlers, percentages had changed to 13.4% Native American , 9.4% African American, and 77.2% white. By 1907 statehood, those numbers changed again to 9.1% Native American, 11.8% black, and 79.1% white. As white immigrants to the state multiplied and blacks increased slightly during the years before statehood, the percentage of Native Americans decreased dramatically. By 1900, following a series of land runs, Oklahoma Territory to the west was already 92.3% white--a fact that helps explain the racism we will soon see. The Rise of All-Black Towns As Indian Territory slaves gained their freedom, those who were not welcome to remain where they had lived or who chose to move were suddenly in search of new places. Soon they began forming their own black towns, complete with businesses, banks, schools, and newspapers. Although territorial Oklahoma was not the only place with all-black towns, it boasted one of the largest concentrations, especially in Indian Territory. As news spread, other freedmen arrived from across the South, contributing to the early success of these towns as people congregated for mutual protection and economic opportunity. While this was the heyday of black towns, they would soon face hard times as 1907 statehood led to the immediate passage of Jim Crow Laws that drove many blacks out of Oklahoma. Also, In the years following U.S. passage of the Dawes Act, the Five Civilized Tribes began losing large portions of the lands promised "as long as the grass grows and the water flows." The government cased control of a large portion of Indian Territory lands--allotting small homesteads to eligible tribal members, mainly heads of households and single adult tribal members; reserving other lands for towns, schools, churches, and cemeteries; setting aside lands believed to hold mineral deposits, including oil; and selling many town lots and other non-allotted lands to incoming white settlers. Ragtime in Territorial OklahomaIndian Territory and Oklahoma Territory were not hotbeds of ragtime--at least, not as far as available newspapers were concerned in the years leading up to Scott Joplin's visit. Newspapers most commonly carried advertisements for touring companies featuring ragtime songs, bands or orchestras, and dances. Those ads reveal sufficient local interest to draw in performers. One unusual item appearing in several territorial Oklahoma papers reported on a group of Georgia prisoners, all serving life sentences, who performed in striped prison uniforms and leg shackles and were said to "surpass all others known in rag-time music, negro melodies, [and] buck dancing." Cakewalks As far as local ragtime-related events are concerned, cakewalks were the most common through 1904, many organized as fundraisers for churches or charities. This one from Guthrie, which would become the state's first capital in 1907, serves as a typical example. The military-style drill conducted by young women marching with brooms rather than guns had been such a hit at the A. M. E. church in April that it became an added feature at the cakewalk. Clearly, the newspaper approved of the event and encouraged white community members to support the cause. This was not always the case. Several newspapers published hate-filled racist remarks about the black communities in Guthrie, Kingfisher, and Enid. Coverage of the "cakewalk riot" in Enid, Oklahoma Territory, ran from May 1899 well into 1901. This report published in Ardmore is one of the mild ones although blaming the blacks. While this early article blamed black attendees, the story changed over time, placing a large share of the blame on white agitators and gunmen. The 50 shots increased to as many as 175, punctuated by brickbats and stale eggs wielded by whites. A handful of black attendees were arrested with no reported case outcomes. Four white men faced a grand jury: a wealthy real estate man said to be the ringleader, the Enid town marshal, and the town night watchman. Enid's hate-filled Garfield County Democrat proposed postponing trials until after the next election so that officials soft on the cakewalk crowd (not the wording used) could first be voted out. About a year later but before the trials, that paper also suggested another cakewalk, saying "walkers are getting thicker and thicker," presumably implying that a few more members of an expanding black community could be shot. Other papers, such as Stillwater's Daily Gazette, spoke of how "a mob" of prominent citizens had "bombarded" the cakewalkers, eager to drive them out of Enid. In the end, juries acquitted each of the white men. Some papers described the highly-publicized "cakewalk riot" as a political event making it impossible to determine the facts. Whether bare-bones facts, supportive remarks, or sensationalism, territorial Oklahoma cakewalk articles offer no information about the music accompanying the dancing, as is nearly always the case in other places as well. Anecdotes and Ragtime Balls Probably the most frequent mentions of ragtime appeared in jokes reprinted from other papers across the country. Local anecdotes rarely appeared, and when they did, they typically attacked ragtime music. One of these attacks had an Oklahoma flavor: Even today, several towns host annual rattlesnake roundups, and hikers throughout the state keep an eye on the ground. Founded shortly after the 1889 land run and already located on the Chicago, Kansas, and Texas Line, El Reno considered another potential benefit of its local ragtime--increasing the community's prosperity by attracting the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Line. Although the "KATY" line already passed through Indian Territory, if the railroad considered local ragtime in its planning of an Oklahoma Territory spur, it favored Oklahoma City's music scene about 29 miles to the east. The proposed new branch reached OKC in 1903. Other local ragtime dance announcements specified whites should attend in blackface, such as this one advertising a dance in nearby Sulphur: The beautiful natural landscape encompassing the sulphur springs spoken of was bought from the Choctaws and Chickasaws by the federal government a year later and eventually developed into the Chickasaw National Recreation area. Early Territorial Ragtime Composers and Compositions Although several Oklahoma rags were performed during Ragtime for Tulsa's concert given as part of the Oklahoma Statehood Centennial celebration, I have found only two in available Oklahoma newspapers 1904 or earlier--the first a ragtime song, the second a piano rag. Albert Ross Cottle and Robert Cortland Fleming, lyricist and composer of My Indian Queen, were young deputy U. S. marshals, originally from Kansas but assigned to Wewoka, Indian Territory's capital of the Seminole Nation, founded by mixed-race black Seminoles. By the time Joplin reached Oklahoma, Cottle and Fleming had been promoted to the larger Muskogee office about 90 miles northeast and one of the places Joplin would stop. Known in Muskogee as "the musical deputies," each man reportedly played piano, guitar, mandolin, and cornet, and each had previously composed a march--Cottle's titled Indianola and Fleming's The Battle of Guiguinto, which took its name from the Philippine-American War of 1899-1902. Born in 1880, Cottle served as a federal marshal throughout his career. His 1970 death followed many years working out of Tulsa's Federal Building. A year younger than Cottle, Fleming was not as lucky. In 1910, at age 29, he died in the village of Cloudcroft, New Mexico, where he had gone with wife and young daughter in a battle for his life. Although his obituary does not identify the nature of his illness, quite likely it was tuberculosis. As one might guess from the obscure title of his march, R. Cortland Fleming had served with the Kansas infantry in the Philippines where he was a member of the band, not a combatant. His military headstone appears on Find-a-Grave. Edward Alexander Windell copyrighted The Pirate Rag two days before his 27th birthday, but Pieratt & Whitlock Music Company had advertised it for sale before Christmas, 1904. Born in Illinois, 12-year-old Ed Windell appeared in the 1890 Oklahoma Territorial census with his parents, and by 18, if not earlier, he began performing for special events, including department store sales and parties in towns such as Perry and Waynoka. Athough Windell usually played solo piano or performed with a violinist or cornetist, a 1919 paper mentions a violin solo. In 1906, Pieratt & Whitlock copyrighted Windell's Auto; march and two-step for piano. Sometime before 1911, he purchased the Electric Theater in Waynoka, a railway center 70 miles west of Enid. I have not been able to determine whether Windell played theater piano or organ. Territorial Oklahoma Ragtime Pianists Along with the three white Oklahoma ragtime composers, I came across three Oklahoma ragtime performers--the first Native American, the second most likely African American, and the third African American. Unfortunately, I have found no additional information that I feel confident matches these three performers. The Joplins Travel Through Indian Territory On June 14, 1904, Scott Joplin and Freddie Alexander married in Little Rock, Arkansas. Evidence indicates that the newlyweds arrived in Indian Territory sometime before the end of the first week of July. One would like to think that newspapers might take note of the pair's status as newlyweds, but none of the papers mention Freddie. For Scott Joplin this would have been a business trip more than a honeymoon. He had music to sell and to play, a new wife to support. Ironically, the main hint of Freddie's presence in Indian Territory comes to us only after her untimely death in Sedalia on September 10. In KIng of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era (2nd ed., 2016), Ed Berlin quotes a brief notice published the next day in Sedalia's Sentinel, Capital, and Democrat, but it provides only basic information. Next, he reprints the detailed "Demise of Mrs Joplin" from the September 16 Conservator, Sedalia's black weekly. Perhaps because I was reading the full book when it was issued rather than focusing on each detail, I missed something in King of Ragtime that I noticed recently when I came across the Conservator article in an online newspaper archive. This time a detail jumped off the page--a statement that Freddie "had traveled some with Mr. Joplin who was billed to give piano recitals in western towns." Since Oklahoma is immediately west of Arkansas, I changed my search terms in that archive to include Oklahoma and also checked the Oklahoma Historical Society newspaper archives. Although what I found has probably been found by others, I have not seen these Joplin items anywhere and believe they deserve attention. King of Ragtime provides a more detailed overall account of Joplin's Missouri activities and of press coverage during his brief marriage to Freddie. Berlin mentions Freddie's travel with Joplin after marriage, no doubt because he had read that in the Weekly Conservator. Because he does not identify the nature of that travel as he normally would, he presumably could not do so before the book went to press. My goal is to fill in what I can of the gap in the Joplin marriage, repeating little of what has already been covered well. When new information calls any part of the previous narrative into question, as it sometimes does, I will address those differences. I suspect Joplin made more stops than I have located. Since we don't know when the Joplins left Little Rock, they may have made earlier stops than the two I can document in Indian Territory. Also, as you will see, several days pass between stops, causing me to suspect one or two others. I also have reasons to believe that a previously known stop in Kansas was not a separate trip Joplin made from Sedalia during Freddie's illness, but the last place they visited together. Passing Through Muskogee On July 7, the Joplins arrived in Muskogee, named for the Muskogee Creek Indians and serving as the agency headquarters for the Five Civilized Tribes. The town had its white people, of course, and also a booming black business district on Second Street. Although the second postcard resembles a scene from antebellum days, Muskogee's cotton growing, like the rest of Oklahoma's, would soon be all but forgotten as 1904 saw the construction of the first oil refinery that led to a local oil boom, the arrival of oil men, and rapid town growth. Between 1900 and Oklahoma statehood in 1907, Muskogee grew from 4,254 to 14,452, making it the second largest town in the new state, behind Oklahoma City. Although the readily available Muskogee newspapers tell us little about Muskogee's ragtime scene, the following comment on a touring company suggests that ragtime was a box office draw, and the thriving black community almost certainly held its own ragtime events. The single Joplin item appearing in the Daily Phoenix leaves us wondering what Scott Joplin did while in Muskogee. It provides no information telling us when he arrived or how long he stayed. Readers of Berlin's Joplin biography will have encountered several times Joplin appeared in some new town to sell music, and we can guess he supplied the local stores with his latest compositions, including The Chrysanthemum, which Ed Berlin points out was "Respectfully dedicated to Miss Freddie Alexander, Little Rock, Ark," now Joplin's wife. Did Joplin perform in Muskogee? I can't say although it seems likely. The Phoenix noted his success. Many people probably knew The Maple Leaf Rag. The Sedalia Daily Conservator's article published after Freddie's date reported that the trip's purpose was to fulfill Joplin's billings for piano concerts. The town's sizable black community should have been interested. With several days between this newspaper item in Muskogee and his next documented stop, we can assume he was doing what he could to make money in Muskogee, nearby, or in route to Vinita. Not far from Muskogee, were several black towns; Redbird to the north and Taft to the immediate east are known to have had rail service to and from Muskogee. On the way to Vinita were places such as Wagoner, Chouteau, Pryor Creek, and Big Cabin, any of which might have served as another quick stop, such as dropping off music. Of course, Joplin may have busied himself in bustling Muskogee until traveling directly to Vinita. Performing in Vinita The Joplins probably arrived in Vinita by July 12, and this must have been an unusual venue for him. Founded by Elias C. Boudinot, the son of one of Chief John Ross's assassinated Cherokee rivals, Vinita now had white and black residents, but retained a sizeable Cherokee community. By 1904, its population was between 2,239 and 3,157; those figures represent its 1900 Indian Territory and 1907 statehood populations. Based on items in the daily and weekly papers, folks in Vinita seemed to like ragtime, whether performed by the black community or the town band. Vinita papers were far more generous with their press coverage than Muskogee had been. Instead of a single item, they published several. Joplin's first stop must have been the music store where he could place and demonstrate his music, begin his local promotion campaign, and possibly make useful connections. Since arrival, he must also have made the rounds of newspaper offices, prompting publicity in another of the town's weeklies. Joplin made a good impression, for the papers readily praised him with the words "noted" and "of merit." Although Ed Berlin cites evidence that Joplin planned to remain in Sedalia for some time, Joplin must have conveyed that he lived in St. Louis and was returning there. Perhaps he felt the city would impress people more. Since he had lived in St Louis for several years before returning to Sedalia, he probably regarded this as a harmless little white lie. The last sentence raises a less obvious question, however. Why would Joplin tell the newspaper that he was headed home if he had previously arranged to play in Vinita? Recall that the Sedalia Conservator article announcing Freddie's death spoke of traveling to places where he was "billed to give piano recitals." The Muskogee paper did not mention a "recital" or performance of any type although that omission doesn't preclude possible performances. We will soon see that Joplin did play in Vinita at more than the McManus music store, but nothing clearly indicates a previous booking. "Scott Joplin . . . is in town" could have announced the news that the anticipated pianist has arrived, but it could also have meant that he had shown up unexpectedly. Also, the first mentions of a performance in Vinita were published in the Daily Chieftain on the morning of that performance. The earlier newspaper items indicate that Joplin had been in town at least two days. On what seems to be no earlier than the third day, two announcements appear in different columns of the front page: Perhaps the paper merely needed to fill gaps in its columns, but the fact that it printed a third similar item on page 3 hints that someone in the Cherokee Club may have asked the paper to do all it could to spread the news. If this dance had been planned for weeks, why wouldn't the Cherokee Club have promoted the dance earlier? The frequency of these announcements in the same issue and the absence of earlier announcements suggests that the dance may not have been scheduled before Joplin's arrival. With Joplin in town and surely willing to earn money, he may have been soliciting opportunities, or a club member may have seized one. In either case, why not hold an impromptu dance? Looking at other issues of the paper, I have noticed that the Cherokee Club dances were for members only, with the exception of others, such as dates, invited by members. The dances were not public events. The more notice members received, the more likely they would attend. A group of young single men had founded the club the previous summer and set about outfitting their club rooms. According to the July 3, 1903 Vinita Daily Chieftain, the smooth, newly installed dance floor "rivaled an English dance floor," and "a handsome new piano" had been delivered shortly before the first dance. The club rooms also included a billiard room, a library, and a women's dressing room. Given the club's name and the town's history, I had wondered if club members were Native American or white. A list of couples was published after most dances, and with the aid of Indian Territory census records, tribal rolls, and the Dawes list, I have been able to identify nearly all attendees as tribal members, mainly Cherokee. Only one is listed as full blood, many as little as 1/4, 1/8, or 1/16, indicating how the Cherokees had intermarried with whites for many years. A small percentage of attendees, including a couple officers, identified themselves as "white" in public records. However, I noticed two that identified as white in some records but as Indian in others. Either way, the club members and their dates were primarily mixed race and ranging in age from teenagers to early twenties. A day after the dance, the Daily Chieftain declared it a success. Not only did the young club members and their dates turn out, but they had invited several outsiders. Although unclear whether the "fully fifty couples" were all members and their dates or included the visitors, more than 100 people heard and danced to Joplin's music that night. Initially, I thought the visiting guests, the Owls, might have been a Vinita team with little or no other relation to the Cherokee Club. However, on August 1, the Daily Chieftain clarified the situation after the Owls won a rematch. The Owls and the Cherokees were baseball rivals, representing two of Vinita's most popular social clubs. On dance night, the teams had set aside their sports rivalry. The Cherokees had also ensured good attendance for their visiting pianist. J. F. Ledbetter, one of the out-of-town guests, was a U.S. marshal in Muskogee. It's somewhat surprising that My Indian Queen composers Cottle and Fleming, also Muskogee marshals, hadn't accompanied him. Hopefully, they had heard Joplin play during his Muskogee stop. A week after the dance, the next issue of the Leader carried its own brief followup. The dancers enjoyed themselves, unanimously proclaiming it "the year's best dance" and concurring that Joplin deserved his title as the King of Ragtime. He could count the Cherokee Club dance as another of his successes. Beyond Indian Territory Probable Last Stop on the Tour Although it has been believed that financial need may have forced Joplin to leave a bedridden Freddie at the Dixon home in Sedalia to travel on July 20 to Fort Scott, Kansas, I believe Fort Scott was another stop--probably the last stop--on the tour from Little Rock through Muskogee and Vinita. Several facts lead to this suggested change in the Joplin timeline. First, anyone traveling on the MK&T "Katy" Railroad could not reach Sedalia from Vinita without passing through Fort Scott. Second, the Conservator's September 16 article about Freddie's death ("Demise of Mrs Joplin") describes her fatal illness as "of seven weeks duration." If the Joplin's reached Sedalia as late as Saturday, July 23, seven weeks would remain between her confinement to bed with a bad cold and her death during the afternoon of Saturday, September 10. Finally, once back in Sedalia, Joplin's first performance seems to have taken place at Liberty Park Hall on July 28, indicating the Joplins had time for the Fort Scott stop. Berlin's account of the July 28 Sedalia musicale reveals Joplin's selections, his fellow performers, and an attendance detail--the fact that 200 people attended, all white--due to one of the dailies announcing that the musicale was "for whites only." In the August 5 issue of the Conservator, editor W. H. Huston, criticizes black Sedalians for staying home when "cultured entertainments are prepared for the intelligent Negro." Huston cites low attendance during a prominent black traveling troupe's performance at Wood's Opera House a few months earlier and the recent failure to support Joplin's concert by giving him the "encouragement and patronage that his efforts merit." We do not know at what point Freddie began suffering from the cold--or what was assumed to be a cold--that caused her to take to bed when the pair reached Sedalia. This close to home, some type of symptoms had surely developed, yet a nineteen-year-old would typically ignore a cold, especially when something fun for her and something important to her new husband lay ahead. From the event announcement, the July 20 Fort Scott venue resembles the Cherokee Club venue in Vinita--more music performed for a club, perhaps another dance. After I searched for the Goats in a few previous months of Fort Scott newspapers, that looked like a logical conclusion. Although the Goats appear in local papers more as a baseball club, they had also recently moved their clubhouse over a bookstore, bought a new piano, and held an occasional dance, but not with the Cherokee Club's frequency. Berlin comments on Fort Scott's description of Joplin "as a composer of classical . . . music." Despite Joplin's having composed no such music, this quotation might indicate that Joplin's aspirations led him to convey that idea. Similarly, as in Vinita, Joplin portrayed himself as living in St. Louis although he had recently moved back to Sedalia and planned to take Freddie there. Other than these discrepancies with the truth, this announcement tells us mainly that Joplin had visited and performed in Fort Scott. However, Joplin's Fort Scott story does not end with with this performance announcement. Joplin was neither performing for another dance, nor giving a recital as spoken of in the Conservator following Freddie's death. Two days later, the Fort Scott Republican hinted at a more interesting story. The misspelling of Joplin's name makes the article more difficult to find in an online newspaper archive, but I found it by searching for "Goats" and limiting the time period to a few days after Joplin's July 20 Fort Scott appearance. With Harry Colbert's full name and the last name of the Jones brothers, I searched again, finding them together. The July 7, 1904 Fort Scott Republican reported that Harry Colbert, along with Johnney and Homer Jones, "colored minstrels," had returned from playing at street fairs in Witchita [sic] and other western towns." The March 29, 1904 Republican reviewed the previous night's local minstrel show, telling us that "Prof. Homer Jones" served as musical director, assisted by his brother. During the first part, Johnney/Johnnie Jones and Harry Colbert sang; during the olio, Colbert and Johnney Jones took on roles of Tambo and Bones. The show ended as minstrel shows often did, with a "genuine old fashioned 'hoe down'" by the full cast, followed by each taking turns "shaking their feet." While Joplin's July 20 Fort Scott show lacked the number of performers for a minstrel show like the one Colbert, the Jones brothers, and many others had put on in town back in March, the Joplin, Colbert, and Jones show may well have included singing, dancing, and jokes for which Colbert and the Jones brothers were known. They had only recently returned from their street fair performances in Western Kansas. Such content likely means that Joplin's summer performance had not been thrown together after he arrived in town on July 20; it would likely take a bit more planning. So when did they organize this show? Evidence demonstrates that Joplin could have met Colbert and the Jones brothers two months earlier. Flashback to April 1904. Joplin had visited Fort Scott on April 23 between two spring visits to Parsons, Kansas. He may have accompanied Kersands and the Georgia Minstrels to Kansas when they left Sedalia or perhaps arranged to meet them in Parsons a few days later. (See King of Ragtime for Berlin's comments about Joplin's friends in the Georgia Minstrels and an entertainment he had organized for the troupe while they were in Sedalia.) After a stop in Springfield, Missouri, on April 18 and perhaps another stop or two between Sedalia and Springfield, the minstrels left Missouri and headed west to Parsons where they performed at Edwards Theater on April 20. Berlin briefly discusses an April 27 Joplin benefit musicale for a Parson's school, and Joplin might have thought he could spend a week productively in the area before that performance venue. With Kersands and company having finished their Parsons performance on April 20 and having moved 26 miles by railroad northwest to Chanute, Joplin set about making money in Parsons. Here's a second possibility: Joplin might have arrived in Parsons with no plans for the April 27 musicale and taken advantage of an opportunity when it arose. Imagine a new African American school soon to benefit from a musicale staged by locals. Imagine being one of those local performers contributing their talents to that benefit. Imagine the school's and the local performers' surprise when someone of Joplin's caliber unexpectedly arrived in town and agreed to play a couple numbers and lend his name to the musicale. Now imagine the increased ticket sales. A hypothetical scenario, sure; but a possibility. Whatever the case, Joplin had time to kill and money to earn. The next day, he left Parsons for Fort Scott. Within the next few days, Joplin returned to Parsons in time for the April 27 musicale. Following that introduction touting Joplin's reputation, the Herald printed the musicale program. Largely comprised of local talent, it included four vocal soloists, three instrumental soloists, and selections by the Parsons Colored Quartet. Scott Joplin, the only outsider, was surely the hit of the show as he played Weeping Willow and, as the finale, The Entertainer. Did Joplin plan the program before the Kansas trip as a means of supporting the school? Although it is unlikely he knew anything of the school before his spring arrival in Parsons a week or less before the performance, did he then propose the musicale? This could certainly be a sign of his benevolence although he would walk away with a portion of the proceeds. Did he volunteer to help the cause after hearing about the planned musicale? Did someone who noticed his presence in town ask him to participate in exchange for a percentage of the take, adding his name to the show to increase profits? These are questions researchers may never answer. More questions arise, potentially connecting Joplin's April Fort Scott visit with his July Fort Scott visit. If Joplin did not need to assemble and rehearse the local talent for April's musicale in Parsons, he had free time on his hands. During what could have been several April days in Fort Scott, possibly as long as April 21-26, did Joplin or Harry Colbert and the Jones brothers--local talent he might have met--plant the seeds that blossomed into the July 20 Fort Scott musicale, likely the finale of Scott and Freddie's tour between Little Rock and Sedalia? Did Scott Joplin look forward for nearly two months to sharing that summer tour finale with his new bride Freddie? Was she well enough by then to attend and enjoy the Fort Scott production? Back Home in Sedalia If the July 20 Fort Scott musicale, assisted by Colbert and the Jones brothers, was the last stop on the summer tour, the Joplins could have reached Sedalia the next day, July 21, with Freddie now suffering from a severe cold that immediately sent her to bed. Her illness largely confined Joplin to Sedalia performances, the first of which took place at Liberty Park Hall on July 28. Ed Berlin cites the next day's Sedalia Capital as reporting a troublesome attendance issue. An audience of nearly 200 would normally be considered a success, but this was an unusual audience for a black ragtime pianist--nearly 200 whites, no blacks. Berlin goes on to explain that one of the daily papers carried a notice stating that the concert was for whites only, and that Joplin's announcement of the error did not appear in the Conservator until the day after the concert. A week later, on August 5, W. H. Huston, the Conservator's editor, criticized black Sedalians for staying home when "cultured entertainments are prepared for the intelligent Negro." Huston cited low attendance during a prominent black road troupe's performance at Wood's Opera House a few months earlier and the recent failure to support Joplin's concert by giving him the "encouragement and patronage that his efforts merit." After Freddie's death, the Conservator credited Joplin with having "administered to every want" throughout her illness although, as Berlin points out, Joplin also needed to earn a living. Everyone interested in Joplin's other Sedalia performances that summer should consult King of Ragtime. The Sedalia Conservator published occasional progress reports of Freddie Joplin's condition. Ed Berlin quotes the August 12 statement that her condition is "somewhat improved" after a recent relapse. Three weeks later, on September 2, the Conservator again updated her condition The best I can tell, Joplin left town only once between the end of the summer tour (about July 21) and Freddie's death on September 10. On September 8, the day Freddie's sister, Lovie Alexander, arrived to remain at Freddie's bedside, Scott Joplin took a one-day trip out of town. Joplin must not have realized Freddie's death was so near. Perhaps he could not face the possibility that his new wife could die less than three months after marriage. Only six days earlier, the Weekly Conservator had reported her gradual improvement. Yet we can guess that Lovie may have been summoned because Freddie had suffered another relapse. Surely, Freddie's sister had not made the long trip so Joplin could go out of town for a day. He could have arranged for someone else to stay with or check on Freddie if she had continued to improve. Whatever any of us might speculate, one fact is clear: On September 8, only two days before Freddie's death, Scott Joplin left for Sweet Springs, a community about 30 miles northwest of Sedalia: Having found that item, I needed to know why Joplin, Huston, and the quartet had made that trip or, more importantly, why Joplin had accompanied them. A targeted online search of the Conservator had yielded nothing more, so I decided to browse the next weekly issue--September 16, the issue I already knew included "Demise of Mrs Joplin." Fortunately, the trip announcement above led me to read the community news column from Sweet Springs where I found at least a partial answer: Sweet Springs would have submitted this news. Not only could Huston not know what had occurred in every nearby black community with its own column in the Conservator, but also the closing "Come again," reveals as much. I was shocked to learn that Joplin had attended an out-of-town picnic on a day that Freddie must have been gravely ill. The only way I can explain such a decision is to believe he felt he had left Freddie in her sister Lovie's caring hands and had the chance to earn some much-needed money, perhaps to help pay medical bills. Freddie's death appeared on the front page of the September 16 Conservator, the note about Huston, Joplin, and the Sporty Boys having their fun at the picnic on the last page--a now permanent but obscure record of Scott Joplin's absence and a memory that may have haunted him when she died fewer than 48 hours later. We might think the situation could not be much worse, but it was. A death did occur on picnic day. Three columns to the right of the Sweet Springs picnic fun, another item caught my eye: Only after seeing this did I pay attention to a long article titled "Our Mother's Death," Huston's eloquent and heartfelt obituary for his 70-year-old mother, who had died in Arrow Rock while he attended a picnic 35 miles away. Well into the obituary, he addresses his emotions, shared by siblings, also absent: We are grieved not so much because of her taking away but because of our not being present during the final hours to hear her last words. She loved us all as only a mother can love. Her constant wish was to see her children once more before the final dissolution. Unfortunately for us, death--that relentless foe, intervened. Objective facts of his mother's death appear on the front page, well hidden in the Arrow Rock news column. Although profoundly impacted by his mother's death, Huston placed her obituary on the back page. He placed "The Demise of Mrs Joplin" on the front page. In the article devoted to Freddie, Huston mentions the location and brevity of the Joplins' marriage, their travel to unidentified western states, and the illness that forced her to bed upon arrival in Sedalia. He speaks of Joplin's attention to "her every want" and Lovie Alexander's Thursday arrival to remain "constantly at her side until death separated them." Huston ends with what he calls "our shallow sympathies" for Scott Joplin's loss: Freddie reportedly died at 3:00 p.m. with her sister Freddie at her side. Strangely, Huston does not report the same of Freddie's husband Scott. Was he present when Freddie breathed her last? He may not have been. Scott Joplin had a show to put on that evening and may have needed to prepare. He may have felt all was well: Lovie was with Freddie. An advertisement in the Conservator promoted Joplin's September 10th D. O. H. Hall show as "Lots of Fun . . . Fun Rain or Shine." Surely the music stopped that night. Well over a century later, the sound of silence resounds. "It is strange indeed that none of Joplin's associates interviewed in later years, including his widow Lottie and his friends Arthur Marshall and Sam Patterson, mentioned Freddie," Berlin writes in King of Ragtime; "Is it possible Joplin had never spoken of her?" Perhaps he could not. Scott Joplin had taken his new wife on an extended trip after their Little Rock wedding. Even if Freddie was well at the start of their tour, at some point she became ill--eventually so ill that she was immediately confined to bed in her new Sedalia home. "The Demise of Mrs Joplin" tells us, "Her death was not unexpected as she had contracted [a] cold which developed into a complication of complaints either of which might have resulted in death." We know of the pneumonia, but what was the other half of that "complication of complaints either of which might have resulted in death"? Did pneumonia kill Freddie, or did something else. After an exhaustive search for death and cemetery records, Ed Berlin learned such records were not kept in Sedalia at the time, at least not for black people like Freddie.

Joplin had attended to Freddie but eventually left her at home for a day while he attended a picnic in Sweet Springs with W. H. Huston and the quartet. Possibly he was absent again at the moment of death. By failing to say that Lovie and Joplin were by Freddie's side, Huston, who had unexpectedly lost his mother while he attended the picnic, could speak volumes. We cannot know for sure one way or the other. Now that Freddie had died, now that the unimaginable had occurred, Joplin must have questioned his decisions and actions, wondering if he should have done differently, if he could have comforted with his nearness, if he might have prevented her illness by not taking her on tour or by cutting the tour short when she first showed signs of a bad cold. Guilt often goes hand in hand with grief. Joplin's quick return to St. Louis could signal his attempt to escape his grief and guilt. No one in the larger city knew what had happened. No one would question his past actions, even silently. No one need know what had happened over the past few months. If Joplin's opera Treemonisha was later inspired by Freddie (and Ed Berlin makes an excellent case for his theory), Joplin may have seen the opera as the best he could do for his dead wife. He could bring her back to life, forever young and full of promise. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed