|

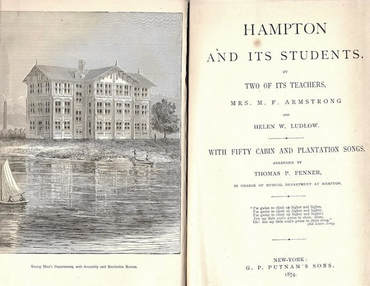

In the first blog entry of my Treemonisha series, I quoted strikingly similar passages from Joplin’s Preface to his opera and one of Booker T. Washington’s important letters, pointing out that a nearly identical passage appeared in another of Washington’s letters. Both men wrote of whites abandoning their plantations, leaving ignorant former slaves to fend for themselves with no one to guide them. I cannot say whether Washington’s words inspired Joplin’s opera or whether Joplin intentionally paraphrased them in his Preface, but overwhelming evidence from fiction and non-fiction sources, from Joplin’s lifetime and ours, demonstrates that Joplin was tackling two important social handicaps of the post-Civil War era—the ignorance and the superstition of the freedmen. Generations of subservience to white masters, who used illiteracy to keep their slaves dependent, left them to cope with their new freedom in whatever ways they could. Because of superstitions largely carried over from African countries that most of them had never seen and because of their related fears, no doubt compounded by years of victimization, freedmen and even their descendants were too often willing to pay conjurors what little money they had to ensure their safety from harm. Although the past seven blog entries have focused on specific hoodoo superstitions that Joplin carefully incorporated into the opera, it’s time to further examine parallels between the opera and Booker T. Washington’s thinking. Because Washington graduated from Hampton Institute, which shaped his beliefs, I will include Hampton and its founder. In 1880, a Little Rock newspaper reported the desecration of a recent grave, consisting of exhumation and the cutting off of three fingers for use in a hoodoo luck bag. The article opened with a prediction that such acts would soon end: The universal system of education adopted since the war has done much toward dissipating superstition among the colored people, and within the next five years there will probably not remain any vestige of the ‘hoodo [sic] box. The belief in ‘hoodo,’ though, is not yet extinguished. (“The Charm Sack,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, June 25, 1880) In Treemonisha, Scott Joplin also conveys his optimism that education will end superstition, albeit gradually. In so doing, he appears to be a disciple of the Hampton-Tuskegee ideology, which shaped black education throughout the South, including—at least to some extent—Sedalia’s George R. Smith College, which he had attended. The next blog post will, in part, discuss George R. Smith. Armstrong and Hampton

Nearly two decades later, Armstrong’s “Twenty-Fourth Annual Report of the Principal” similarly comments on student needs and the current and future rewards of his life’s work: The majority of those now in the School, and of all who apply, were influenced to seek admission by our graduates and other former pupils. . . . While many have risen and are rising above the old level, there is in this wide region—as generally throughout the South—a great substratum whose condition is pitiable, mentally, morally and in many ways physically; held in a sort of bondage by the prevalent ignorance, superstition and poverty. . . . During years at Hampton, its students so internalized the school’s mission that graduates sounded like their principal and their teachers. Having stayed on at the school following 1882 graduation, Georgiana Washington spent ten years assisting in one of Hampton’s dormitories for Native American students, teaching the girls tasks such as washing clothes and ironing. As she prepared for her next career challenge, Georgiana wrote, “Now, after a stay of ten years as a resident graduate, I have been asked by two of the Hampton teachers to go with them to the Black Belt of Alabama and assist in lifting the cloud of ignorance and superstition from my brothers and sisters there” (“A Resident Graduate’s Fifteen Years at Hampton,” The Southern Workman, July 1892). Identified only by the initial E., a veteran teacher in the field wrote his alma mater: I am teaching the same school I first taught when I left Hampton. My school has increased in pupils enough to employ two teachers, myself and an assistant. . . . My people here are progressing regardless of the many obstacles. They are buying homes for their families, are more interested in the education of their children, and are decreasing in superstition and ignorance and immorality in proportion as the light of intelligence increases. (“Letters from Hampton Graduates,” The Southern Workman, Oct.1893) Washington, Hampton, and Tuskegee

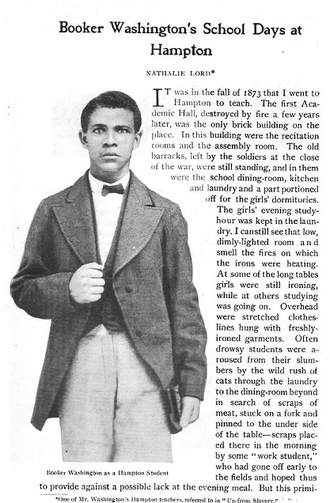

Thus, speaking of the Post-Civil War Southern black, Washington asked, “Starting . . . without a foot of land, without a hoe, without a horse, and unused to self-guidance, . . . his mind befogged with ignorance and superstition, could you have expected him to have travelled very far in the direction of intelligence, wealth, and independence?” (BTW Papers, III, 25)

As Washington struggled to learn and dreamed of a formal education, a young black man, who had learned to read in Ohio, came to Malden, West Virginia, Washington's town. As residents quickly encircled the stranger, eager to listen to him read the newspaper, admiration filled Washington, who later wrote: “How I envied this man! He seemed to me to be the one young man in the world who ought to be satisfied with his attainments.” Joplin-Washington Connections

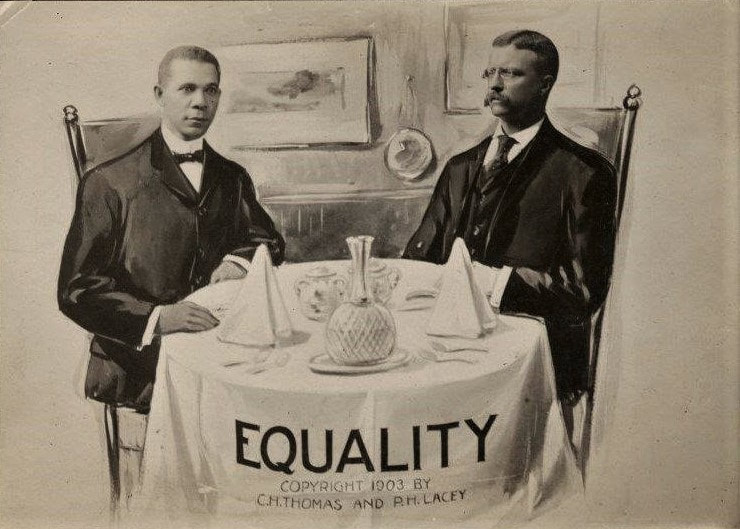

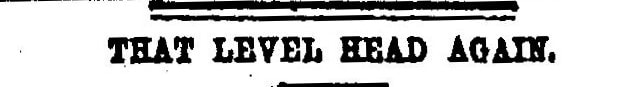

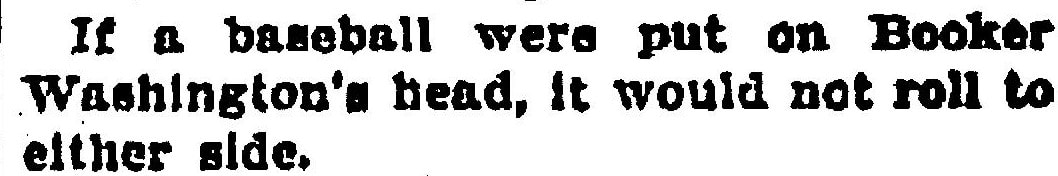

Berlin goes on to discuss the loss of Joplin’s A Guest of Honor manuscript (apparently in Springfield, Illinois), the failure of his opera tour, the failure to submit copies to the Library of Congress to complete his copyright application, and the fact that Joplin appears not to have spoken of A Guest of Honor again—not even to have referred to Treemonisha as his second opera. In passing, Berlin also mentions, “The titles of the two known selections, Patriotic Patrol and Dudes’ Parade, suggesting military practices, are consistent with this hypothesis, as is his comment that the opera has drills" (KOR, 165-166). Although he doesn’t elaborate, I assume he believes that readers know Washington required all male Tuskegee students to participate in military training as one means of instilling discipline. With a failed opera tour and A Guest of Honor relegated to the past, might Joplin have intended Treemonisha as a second tribute to the preeminent black Southern educator? Another small but significant detail occurring early in the opera supports such a conclusion. Just as Joplin’s contemporaries may have understood the significance of small hoodoo references in the opera such as the period before the new moon or the act of making and spitting on a cross mark, they are likely to have understood this detail. Level Heads After Treemonisha reprimands the conjuror Zodzetrick for causing superstition by his conjury, her friend Remus confronts Zodzetrick: Shut up there man, enough you've said; Remus' second line may be one of the most telling in the opera, for it provides a concrete connection between Treemonisha, Armstrong, and Washington. In a March 1, 1886 letter to oil magnate and philanthropist Charles Pratt, Armstrong lauds Washington as "a noble, able, level headed colored man," adding that he had "sanctified common sense” (BTW Papers, II, 268). Although this letter probably was not published during Joplin’s lifetime, Armstrong, others writing of Washington, and Washington, himself, repeatedly used “level head.” The term had played a prominent role in a widely publicized debate during the early 1890s. In "Science and the African Problem" (Atlantic Monthly, 66, 1890), Harvard's Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, geologist and paleontologist, had advocated a scientific study to determine if blacks were physically and mentally "improvable." Hampton's Samuel Chapman Armstrong responded by arguing that blacks were not intellectually less capable, but had lower intellectual achievement--that two centuries of slavery had left them lacking in morality and common sense, without, in his words, "level heads" (Quoted by Donald J. Waters, Strange Ways and Sweet Dreams: Afro-American Folklore from the Hampton Institute, Boston: G. K. Hall, 1983). Washington’s contemporaries frequently praised him and people who espoused his ideas by using the same term. Talking of Washington’s speech two nights earlier at Montgomery, Alabama’s Old Ship Church, the Montgomery Advertiser reported: Pastor Johnston and Nathan Alexander also had kind words of welcome, and then the speaker was presented by Dr. Eager, who paid him the highest eulogy possible, saying that he had a good heart and a level head. (Sept. 29, 1899) Writing about Washington’s book The Future of the American Negro, The Hartford Courant quoted a Washington anecdote beginning, “One of the saddest sights I ever saw was the placing of a three-hundred dollar rosewood piano in a country school in the South that was located in the midst of the Black Belt.” Agreeing with Washington that illiterate rural students needed basic education, not an expensive piano, the paper titled and concluded the article with comments on Washington's "level head": We can infer from the use of "Again" in the headline that readers had seen or heard "level head" applied to Washington many times and that they would understand the article's closing joke. Others continued this trend whether writing to Washington or about him. Alluding to Washington’s recent dinner at the White House, Richard Robert Wright, Sr. of College, Georgia sent Washington the following letter: My dear Sir: Honors have fallen so rapidly upon you that I have not had the time between them to congratulate you upon any of the new ones which have come to you. Noticing to-day in Monday’s paper an account of the speech of Prof. W. H. Councill at Dallas Texas and also the comments of some of the Southern papers on your reception at the White House, I could not refrain from writing the President thanking him for the consideration which he has shown the race through you, if that act is to be considered more than a personal one. I congratulate you upon having been the first one to receive so high a consideration. We all pray that you may continue to carry a level head over a good heart which shall permit you to feel and to do the best and wisest thing. . . . (BTW Papers, VI, 259) Following Washington’s speech at the Negro Baptist Convention in Philadelphia, the Lexington, Kentucky Courier-Journal complimented him for his “level head and practical, good sense” (Sept. 23, 1903). A reporter for the Atlanta Constitution, who had returned from visiting Tuskegee, wrote, “With a level head, a patient spirit and a hopeful heart,” Washington was preparing Tuskegee students “for a future of amity with all men and usefulness to every noble interest of humanity” (Dec. 6, 1903). Washington, himself, used the term when speaking of like-minded blacks. Making light of blacks’ loss of political power they had temporarily gained during Reconstruction, Washington defended the Hampton-Tuskegee goal of economic parity: It did not take the more level-headed members of the race long to see that while the negro in the South was surrounded by many difficulties, there was practically no line drawn and little race discrimination in the world of commerce, banking, storekeeping, manufacturing, and the skilled trades, and in agriculture, and that in this lay his great opportunity. Later, during a fund-raising campaign for Fisk University, Washington argued, "The South is full of strong, useful, level-headed men and women who have been educated at Fisk" (BTW Papers, XII: 173). Ed Berlin’s hypothesis that Joplin composed A Guest of Honor to memorialize Booker T. Washington’s historic White House Dinner rings true. Evidence clearly supports that idea. With the dinner fading into the past but Washington still at the forefront of Black education in the South, Joplin may have drawn upon the Hampton-Tuskegee ideology when composing his second opera. By so doing, he would create a less topical, more enduring tribute. Joplin’s focus on literacy to overcome superstition, and his decision to emphasize Treemonisha’s “level head” by placing that descriptor in Remus’ opening words, both provide some evidence. A closer look at the Hampton-Tuskegee ideology and its possible influence on Joplin will provide more.

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed