|

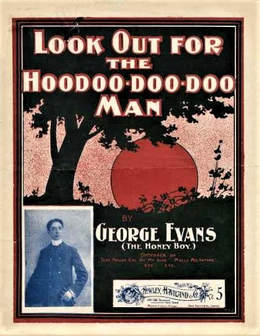

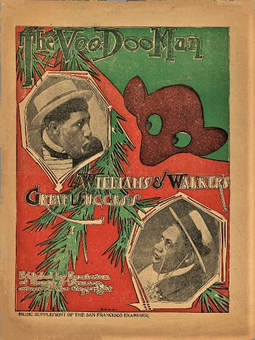

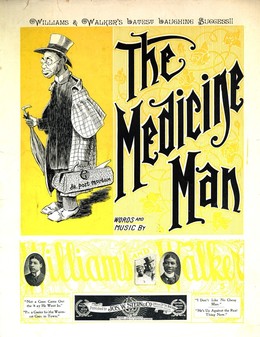

Touching on the etymology of the term hoodoo in his book Voodoo and Hoodoo: Their Traditional Crafts Revealed by Actual Practitioners (1978), James Haskins writes, "Over the years, mostly outside the New Orleans area, these magical practices were subsumed under the general term hoodoo. . . . By most accounts, hoodoo is derived from juju, meaning conjure, but some theorize it may also be an adulteration of the term voodoo. Whatever its origin, the term referred to that body of magical practices that characterized black life in most of North America." In Juba to Jive: A Dictionary of African-American Slang (1994), Clarence Majors offers a broader definition, defining hoodoo as "the spirit or essence of everything, an early African-American religion with origins in West African spiritual life, magic, a conjurer, charm, jinx, or spell." According to Major's definition, hoodoo can refer to the individual magical acts, the spiritual/magical practitioner performing them, magic practices in general, or the very nature of "being," for all things--human, animal, insect, plant, even dirt and stone--were believed to possess spirits and powers. Antebellum Days The Southern Workman (the widely read mouthpiece of Virginia's Hampton Institute, Booker T. Washington's alma mater) comments, "Our good parents of slavery days luxuriated in superstition. They never moved, never thought, never dreamed, never had an itch of the body or a quiver of the eye, never encountered anything at any hour without reading therein a certain sign" (41:4, April 1912). This description approaches, if it doesn't fully reach, the idea of hoodoo as "the spirit or essence of everything," a force deeply infused in life. Katrina Hazzard-Donald, Rutgers Professor of Sociology and author of Mojo Workin': The Old African American Hoodoo System (2013), describes hoodoo as "the glue that held the slave community together." Having lost nearly everything that was theirs or their ancestors' in Africa, slaves could cling to their beliefs. As Eugene D. Genovese puts it in Roll Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made, conjure magic was the only power that seemed to offer an escape from “the doctrine of black impotence which the slaveholders worked incessantly to fasten on them.” Popular Song Context As Ed Berlin points out in King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and his Era, "In treating the subject [of conjurors] with his opera, Joplin was addressing a current and frequently discussed issue." This blog entry, in part, expands on the examples Ed provides. Although believers took hoodoo seriously, popular composers, black and white, drew upon this vestige of African culture and used it to make audiences laugh, sometimes portraying people plagued by bad luck.

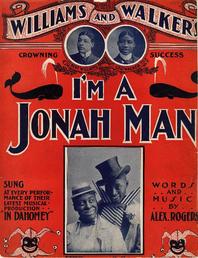

Yet another Witmark hoodoo hit, and perhaps the most famous of all, was Alex Rogers' I'm a Jonah Man (1903), made famous as an interpolation in In Dahomey. Similarly, Bert Williams' made famous the Jonah man's litany of woes:

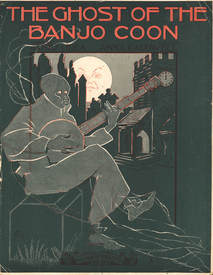

Not all conjurors were so ominous. Fortunately for those believing that a malevolent conjuror had inflicted their suffering, the sufferer could hire a healing conjuror. The Conjure Man (Stern, 1900; words James O'Dea, music Ernest Hogan and Theo. Northrup) stresses the hoodoo man's ability to cast out evil and ensure good health and good luck: Well, look out, coons, here comes de conjure man! James O'Dea and Anna Caldwell's The Ghost of the Banjo Coon tells the ill-fated story of Erastus Henry Johnson, "who kept a getting poor and thin." Inferring that "some wicked coon had put a hoodoo onto him," Erastus sought help and followed the other conjuror in search of a graveyard rabbit's foot with the power to save him. Unfortunately, just as Erastus grabbed a rabbit by the leg, "all his courage fled . . . when the rabbit turned and said:

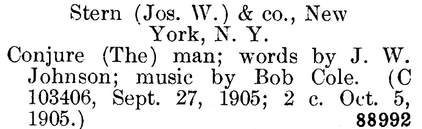

Despite the healing conjurer's help, Erastus' superstition outweighs his desire for a cure, and he flees the graveyard, unable to face up to banjo-playing ghosts, a singing rabbit, and an avian and amphibian chorus. In a second Stern song called The Conjure Man (1905), James Weldon Johnson and Bob Cole present a young woman with sufficient belief in conjure that she attributes supernatural power to a seemingly ordinary young man. Having been told as "just a little gal down souf" that conjure men possess the power of mesmerism, she concludes that the young man must be a conjuror because, no matter how hard she tries, she cannot help loving him. Post-Civil War Historical Context Whatever these songs' spells, sought after cures, or superstitious beliefs, we could easily view the songs as poking fun at quaint beliefs of bygone antebellum days. Certainly, they were composed as entertainment. Yet these superstitions lived on not only throughout the Reconstruction Era of Joplin's childhood, but also well beyond the Ragtime Era. In Mojo Workin', Hazzard-Donald labels Reconstruction as the "golden age of hoodoo practice" and explains several reasons: The tradition blossomed in response to the black community's tremendous psychoreligious need during the postemancipation period of displacement, turmoil, upheaval, and change. Some locations experienced such a phenomenal growth in the number of hoodoo practitioners as to generate a concern for public safety. , , , There were new contingencies to their existence, and the conjurer/treater was one sure resource for dealing with instability, insecurity, poverty, and anxieties that invaded the lives of African Americans of the period. Intensified community anxieties and concerns centered on issues of securing a livelihood, family and marriage, health care, housing, police harassment, legal issues, vigilante terrorism, and the numerous changes of the new freedom. From the Treaty at Appomattox to the composition of Treemonisha, writings about hoodoo and superstitions abounded. A few of them appear below, and others will come in future blog entries as applicable to the specific topic at hand. In 1874, M. F. Armstrong and Helen W. Ludlow published Hampton and Its Students. By Two of Its Teachers. in which they characterized former slaves who had become their students as possessing "a religious fervor often amounting to a form of superstition, so vivid it was, and still is, their belief in all conditions of the supernatural." In the introduction to student papers on conjuring, the April 1878 issue of Hampton's The Southern Workman observed: "A firm belief in witchcraft and conjuration is widespread among these people. Religious faith, even when genuine, does not cast it out. They grow together like tares and wheat in the fertile soil of the negroes' imaginative, excitable nature." Newspapers across the country illustrate this staunch belief's survival in the 1890s. Near death in San Antonio, Texas, Mrs. James Cyle rejected the minister sent to comfort her, insisting, "The debil's done got dis soul of mine." Only the hoodoo doctor could quiet her as he performed a series of hoodoo rituals that ended with tying a rabbit's foot to her big toe. When elderly Lewis Johnson vanished after briefly leaving his wife Eliza 's side for a night walk past a Washington, D.C. alley housing a mortuary, she "knew that the Voodoo had got him." In his essay "Superstitions and Folk-Lore in the South," Charles W. Chesnutt revealed significant, though not yet sufficient, progress in the fight to eradicate superstition: Education . . . has thrown the ban of disrepute upon witchcraft and conjuration. The stern frown of the preacher, who looks upon superstition as the ally of the Evil One; the scornful sneer of the teacher, who sees in it a part of the livery of bondage, have driven this quaint combination of ancestral traditions to the remote chimney corners of old black aunties, from which it is difficult for the stranger to unearth it. (Modern Culture, 13, 1901) Chesnutt was too optimistic. Even in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, St. Louis could not be called "the remote chimney corners," yet St. Louis newspapers carried stories of local conjurors or their victims, such as Lucy Griffin's testimony in court that her neighbor Fanny Henry had hoodooed her by repeatedly sprinkling salt and pepper on the lintels of her house; elderly hoodoo doctor Reuben Dixon's attempt to hoodoo the Governor of Missouri and sheriff of St. Louis County to save his grandson from the gallows; and 35-year-old Joseph Kerner's attempted suicide by cutting his throat with a razor because he wanted to escape the hoodoo placed on him the previous month. Most interesting, however, is a 1912 story that occurred just a block from Joplin's first St. Louis home. Mrs. Lizzie Lewis, of 2710 Morgan Street, paid a neighborhood conjuror $10 for a spell to make her husband run into the river and drown. When arrested, "the 'voodoo doctor' gave his name as Charles W. Prince, 27 years old, and his address as 1323 Morgan street." Prince stated that he had been the neighborhood "clairvoyant and seer" since age thirteen, thus implying that he was at least fairly well known and placing him in Joplin's vicinity when Joplin lived on Morgan Street. Scott Joplin wrote Treemonisha within a quartet of important cultural contexts: an ancient but living hoodoo tradition, a contemporary arts trend inspired by hoodoo, an active scholarly interest in black folklore, and the black community's clash over differing educational theories. We have already seen hoodoo folk beliefs come under attack by Hampton Institute, a white-run school for blacks, as well as by writer/lawyer Charles W. Chesnutt.

The next several blog entries will focus on important hoodoo elements--one or two at a time. To the best of my knowledge, some of these elements will be examined for the first time; others will be reexamined from a new perspective. A second series of blog entries will draw upon education materials from Joplin’s day to shed further light on Treemonisha’s character and on the opera's slow process of cultural evolution. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed