|

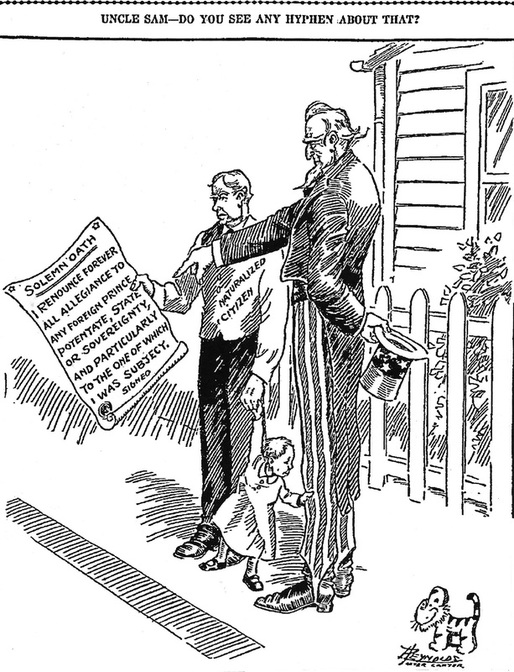

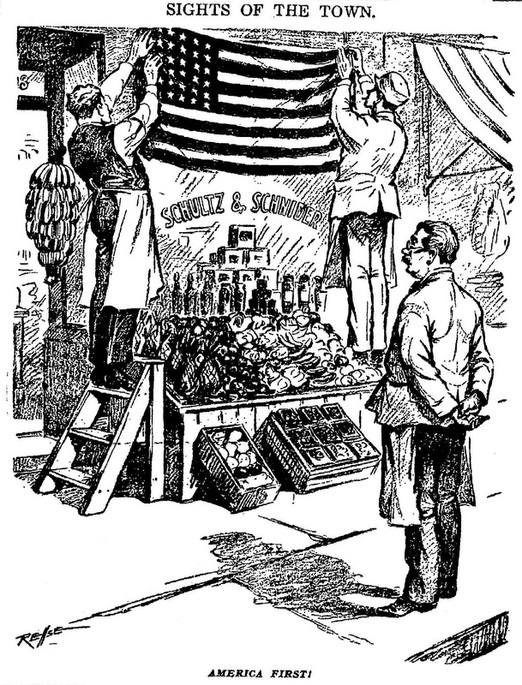

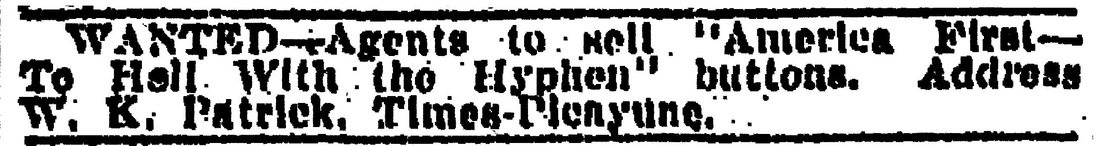

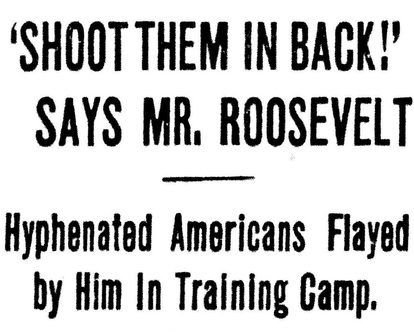

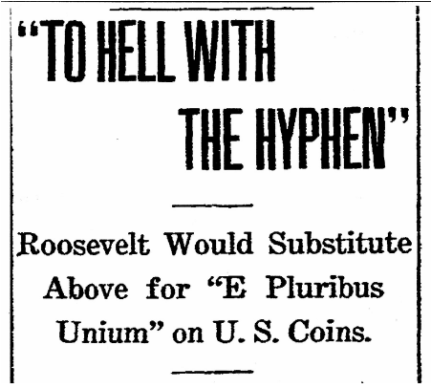

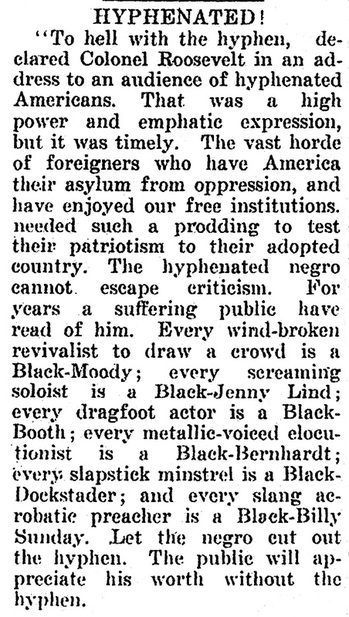

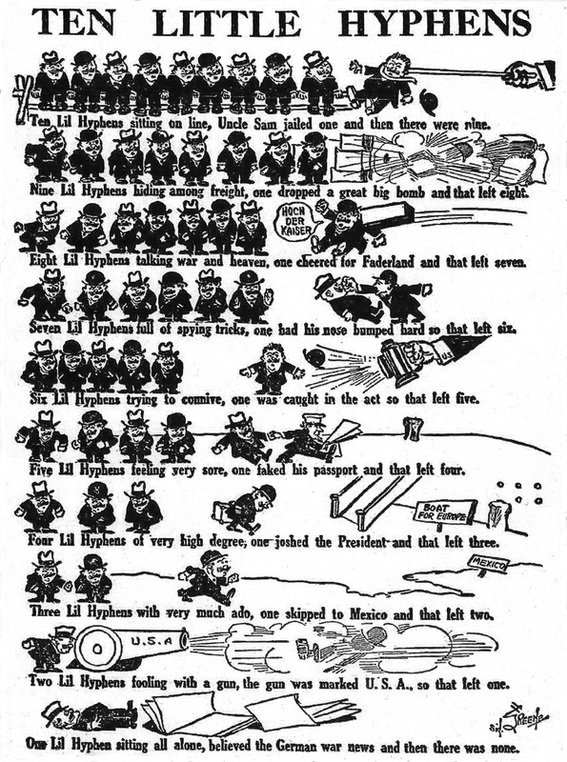

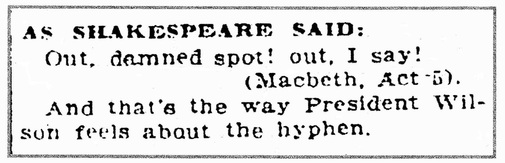

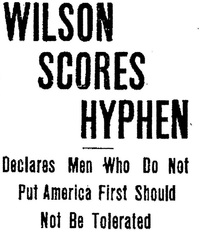

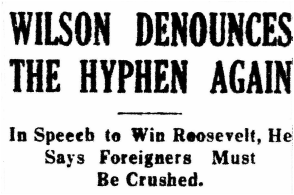

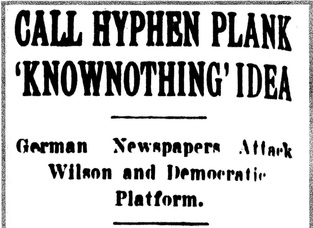

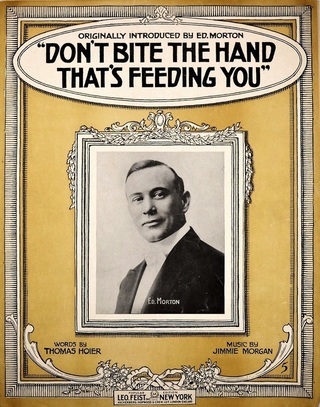

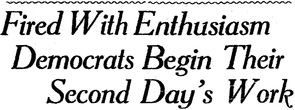

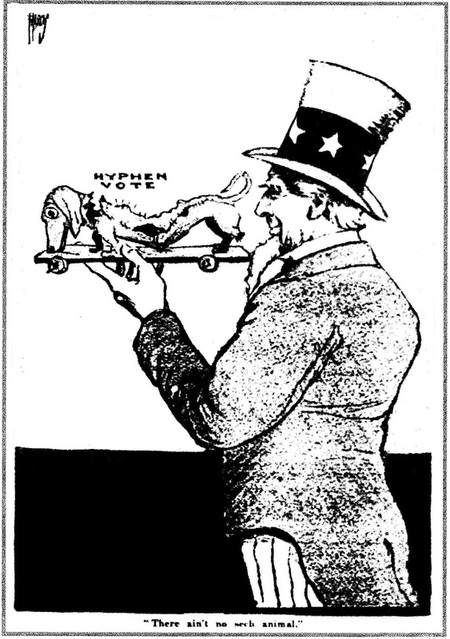

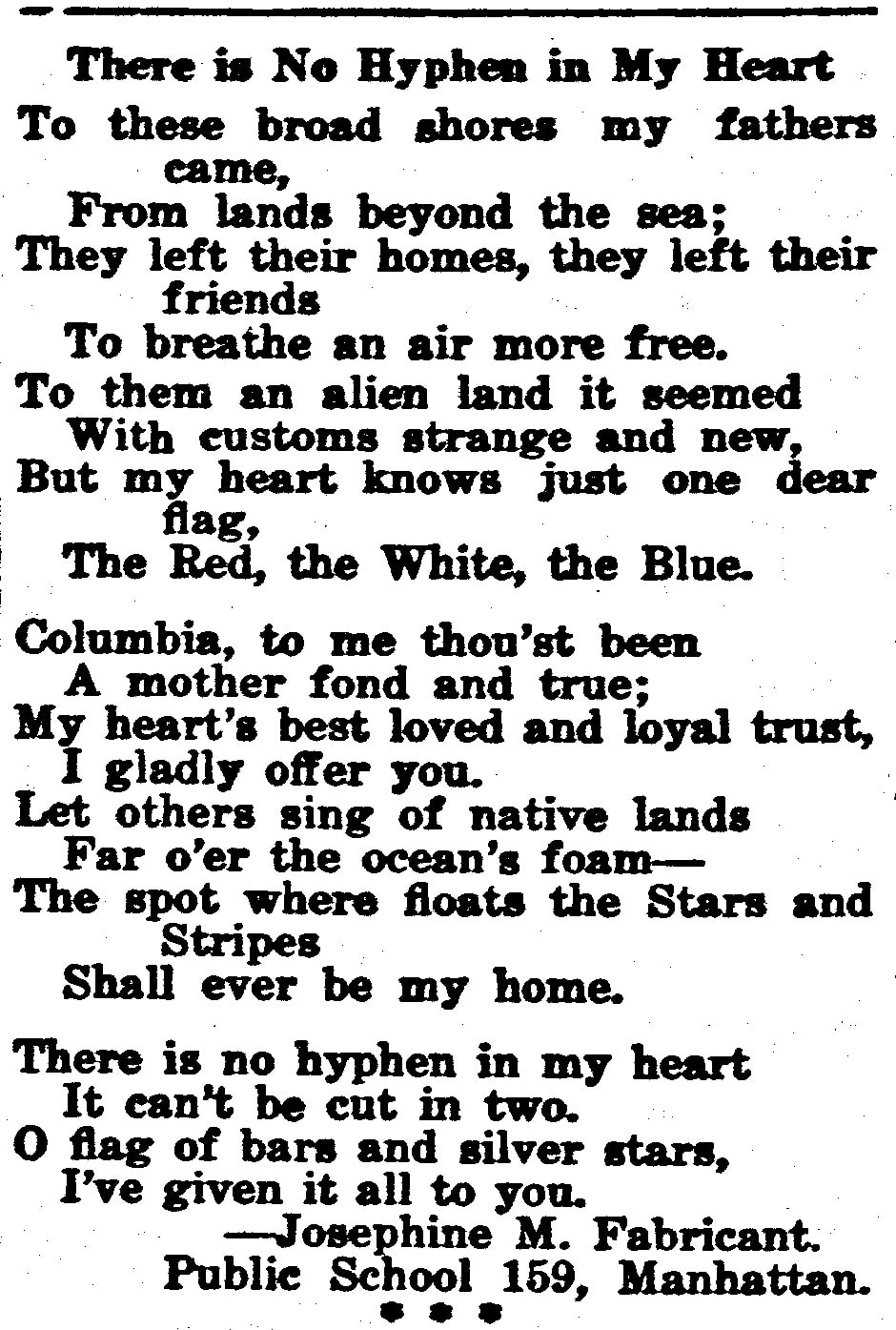

The history of the War on the Hyphen is too interesting to ignore. What's more, it explains and almost certainly inspired the poem that became the lyric of There Is No Hyphen in My Heart--a World War I song William Christopher O'Hare arranged for band and probably for orchestra. Although the War on the Hyphen began innocently enough with an amusing attack on a punctuation mark, it evolved into a war of anti-Americanism--most specifically, a war against pro-German sentiments--which all too easily impacted innocent German American immigrants. In many ways, it parallels discrimination that relegated Japanese American citizens to internment camps during WWII and discrimination that targets some refugee and immigrant groups today. War on a Punctuation Mark In 1910, New York stenographers, typists, and linotype operators were said to be uniting under the banner of the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Hyphens. The suggestion to eliminate the hyphen took root, reappearing in somewhat different forms over the next few years, for example in this 1913 article from Grand Rapids, Michigan: War on a Symbol and a Group The "Hyphenated American" By early 1915, the war on the hyphen had changed into a war on perceived disloyalty. The term "hyphenated American" had been around since the 19th century, but its use mushroomed as war raged in Europe and as President Woodrow Wilson sought to maintain U. S. neutrality. Wanting Americans to avoid partisanship leading to "distress and disaster," Wilson delivered an August 18, 1914 speech to the American people, arguing that the European war's impact on the nation depended on what the American people said and did. Admitting that sympathetic feelings for one's homeland were natural, Wilson stressed that division into "camps of hostile opinions, hot against each other" would, inevitably, "be fatal to our peace of mind and might seriously stand in the way of the proper performance of our duty as the one great nation at peace." In June, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle defined "hyphenated American": A "hyphenated American" is, I take it, an American citizen who divides his affection between the land of his birth or ancestry and this country. So long as he feels only a sentimental regard for the old land and renders first allegiance to the United States, I do not consider the 'hyphenated American' a source of danger. If, however, he, though a citizen of this country, gives first place to the country from which he came, then he is disloyal and, if possible, his citizenship should be revoked and he should be sent back to the country he prefers to this. Tensions Escalate Roughly six months later, on February 4, 1915, Germany established a war zone around Great Britain. Kaiser Wilhelm threatened that his U-boats would sink non-German ships in the war zone, including those from neutral countries. With Germany's May 7, 1915 sinking of the British Lusitania off the Irish coast, more that 1,000 died, among them more than 100 Americans. The United States would not enter the war until 1917. However, heightened tensions between the U.S. and Germany were evident in political rhetoric and public sentiment that did not condone hyphens. Wilson and "America First" With war in Europe making travel too dangerous, the newly appointed Superintendent of National Parks had started the "See America First" campaign, designed to encourage American travelers to spend the $400,000,000 dollars normally spent abroad by, instead, visiting national parks at home. In an April address to the Associated Press, President Wilson shortened the National Parks System's motto for his own political purposes. "See America First" became "America First." Through use of this motto, Wilson drove home his point that loyal citizens must consider the nation their top priority "first, last, and always." "America First" and anti-hyphen sentiments affected many German Americans living in the U.S. My mother's immigrant and first generation grandparents, for example, went silent about their background, never speaking of it even as the years passed. To fit in and live above suspicion, German Americans needed to blend in. Combining Wilson's new motto and the anti-hyphen hype, New Orleans' Times-Picayune was soon recruiting salesmen for buttons declaring "America First-To Hell with the Hyphen." The Times-Picayune expressed its belief that immigrants would probably be among the first to support a campaign for Americanism but agreed that they should be Americans, not hyphenated Americans: Naturalized citizens ought to be better and more loyal patriots than are those who were born in this country, for the latter could not avoid being citizens of the United States, while the naturalized citizens became such through choice and abjured the land of their birth, so as to enjoy the honor of being an American. A man who would forswear his county should have no objection to have the hyphen banished. If you are an American, you cannot be a Frenchman, or an Irishman, or an Italian, or a German. Let it not be 'American First,' but let it be America only, let there be no hyphen to damn. Roosevelt and Hyphenated Americans As Traitors Inspecting a military training camp for professional and business men, former President Theodore Roosevelt vehemently attacked the hyphenated American: When the time comes hyphenated Americans will fight side by side with us or they will be shot. They will be given the opportunity to be shot in front or accept the certainty of being shot in the back. Speaking in September of members of a German-American organization who had announced they would not enlist in the event of war between the U.S. and Germany, Roosevelt declared: If this statement is correct, the gentlemen in question and those for whom he spoke are traitors and in the event of war should be dealt with in summary fashion. The hyphenated American has been shown in actual practice to be loyal only to that part of his title which precedes the hyphen. . . . Their place is not here. Their place is in Germany, in the trenches. Perhaps inspired by Roosevelt, in an October 10, 1915 sermon on "Hyphenated Citizenship and the Kingdom of God," Rev. H. W. Knowles, First Presbyterian Church, Duluth, Minnesota, declared hyphenated Americans traitors to the country: Current events in life often have a direct bearing on and most vividly illustrate Biblical truth. Just now among the striking issues in our land is that of divided citizenship. It is not to the discredit of any one of foreign birth or blood to feel deepest sympathy with the land of his birth or forefathers in the crucial struggle. It would be a discredit if such a person had no feeling either way. There are others to whom this criticism applies in claiming kin with other nations. But the prominent activities of those designated by the above term is the live issue. The placing of the adjective of country, be that country what it may, before the noun American is regarded as treasonable and rightly so. Changing the Motto on American Coins Later in October, Roosevelt echoed the phrase "To Hell with the Hyphen" in reference to any hyphenated American retaining a dual allegiance to homeland or ancestors' homeland. Having previously used executive order to remove "In God We Trust" from coins because, as Roosevelt insisted, they were too cluttered with mottoes, he now suggested replacing "E Pluribus Unum" with "To Hell with the Hyphen." Assuming the phrase had originated with Roosevelt, the St. Albans [VT] Messenger remarked, "It's a clever thing sprung by a gifted phrasemaker. And while it won't go on the coins, it's sure to pass [into] currency of common speech." A Black Newspaper's Slant on Hyphenated Americans In the nation's capital, the Washington Bee expressed a black American viewpoint. Noting how white people frequently used a hyphen to compare a black person's accomplishment to famous white person in a similar field, the paper suggested that eliminating the punctuation mark might increase respect for black Americans: Hyphenated Americans in Song and Verse Parodies By the end of the year, Anti-American sentiments were running high, and the New York Telegram printed this parody of "Ten Little Indians," depicting the many ways hyphenated Americans, now simply called "Hyphens," might prove disloyal and disappear. The New York Sun published a poem using "To hell with the hyphen" as its refrain, drawing loosely on Sir Walter Scott's The Lay of the Last Minstrel: Este Americanus Incumbent President Wilson's Pre-Convention Campaign, 1916 Wilson's anti-hyphen stance was so well known that newspapers joked about it and used it in headlines. On Memorial Day, 1916, at Arlington Cemetery and two weeks later on Flag Day at the Washington Monument, the President verbally attacked hyphenated Americans, regarded as threatening his reelection. In the first address, he charged them with opposing "the purposes of the nation and called upon all young men to perform voluntary service." In the second, he accused hyphenated German-Americans of political blackmail. "Do what we want you to do in the interest of one side in the war or we shall wreck you at the polls," Wilson said they demanded. He responded to the alleged demand by saying, "America will teach these people that loyalty to the flag is the first test." Democratic National Convention, St. Louis Running for reelection, Wilson insisted that the Democratic Party include his "Americanism" plank in its national convention platform. The plank, drafted by Wilson, condemned any hyphenated group's attempt to influence "public representatives" and labeled such political activities "subversive" and those involved in them "conspirators." With the June convention held in St. Louis, a city with a large German American community and German language newspapers, Wilson had to know that the plank would arouse protest but may have already written off the German American vote. Also, he would have known the overall popularity of his "Americanism" stance among staunch American patriots, who frequently harbored anti-immigrant sentiments. Three sample convention headlines, including one comparing Wilson's plank to mid-1800s anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know Nothing party views. Through the early 20th century, political parties could count on composers churning out original songs in time for national campaigns . Performed on vaudeville stages across the country during the pre-convention campaign season and already sung by American soldiers patrolling the Mexican border, Don't Bite the Hand That's Feeding You was the ideal song to suit Wilson's anti-hyphen plank. Audio source: University of California, Santa Barbara Library; Edison Blue Amberol 2948, 1916 Presidential Election and the Hyphen Vote In November, when a substantial number of German Americans voted for Wilson and those opposing him failed to prevent his reelection, a New York Times editorial cartoon depicted the weakness of the "hyphen vote," captioning the drawing "There ain't no sech animal." Despite Wilson's avoiding the label "German-American" when speaking of "conspirators," the crushed dachshund conveys everyone's understanding of his target. Sample Charges Against Hyphenated Americans, 1917 Throughout 1917, newspapers expressed distrust of hyphenated Americans or recounted charges against them: Wichita, KS Jan. 28, 1917 The Hyphenated American and Josephine Fabricant's There Is No Hyphen in My Heart, 1918 At the beginning of 1918, the University of Maine's President published a brief article in the Journal of Education in which he set forth rigid requirements governing teachers of German and ultimately of other subjects, such as government and history, where they might easily convey pro-German sentiments. Teachers could easily interpret his article as a threat to their jobs: Every teacher should be a citizen of this country. Those of foreign birth should be so completely naturalized that all trace of the hyphen has been removed. . . . It is very important that the teachers of German in our secondary schools and colleges be men and women of undoubted loyalty. This will mean in general that they will not be of German blood, or, if of German blood, far removed from the Fatherland. It is very important that no opportunity be given in the schools of the country for the German propaganda that has produced the traitors and plotters that are now giving the government so much trouble. Possibly feeling the need to declare her undivided allegiance to the United States, Josephine Fabricant, the daughter of Czech immigrants and a New York Public Schools teacher, published a patriotic poem that appeared in newspapers and then in the same education journal. Ariadne Holmes Edwards soon set Fabricant's poem to music, and William Christopher O'Hare arranged it for orchestra. During World War I, anti-German sentiment and strategies to ensure Americanization and prevent any other non-patriotic activity became increasingly common in the Journal of Education and other education-related publications. Good Lord, deliver us from the hyphenated American, the pro-German, the spy, the profiteer, the pacifist, the slacker and all who would retard the prosecution of the war for human rights, human happiness and the establishment of a permanent world-wide peace. --Rev. Henry N. Couden, Chaplain of the United States House of Representatives, August 21, 1918; Journal of Education, Sept. 12, 1918 Following a reference to Fabricant's There Is No Hyphen in My Heart lyric, the voice of New York City Public Schools--a publication called School--spoke of the school system's success in assimilating immigrant students. The writer closed with the belief that Fabricant's lyric accurately spoke for most German Americans: The American soldiers of German birth, or origin, who by the thousands and thousands fought to redeem Germany from the curse of militarism proved that that song rang true as the gospel of their schools. --November 1918 The choice of "American soldiers of German birth" rather than "German-American soldiers" would have been intentional within the context of contemporary sentiment and the poem/lyric it had inspired. WWI and "The Lost Hyphen"

The Lost Hyphen Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed