|

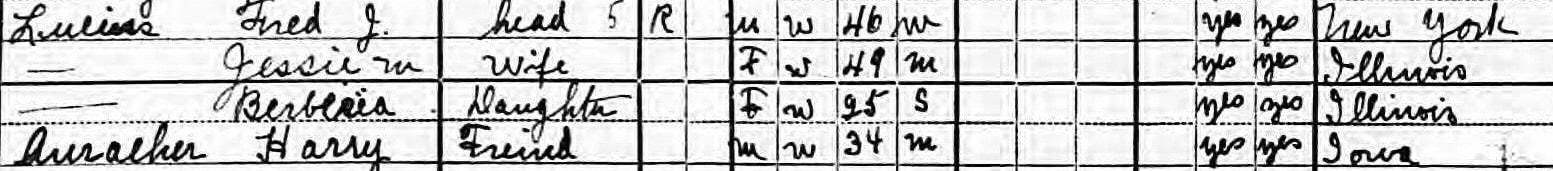

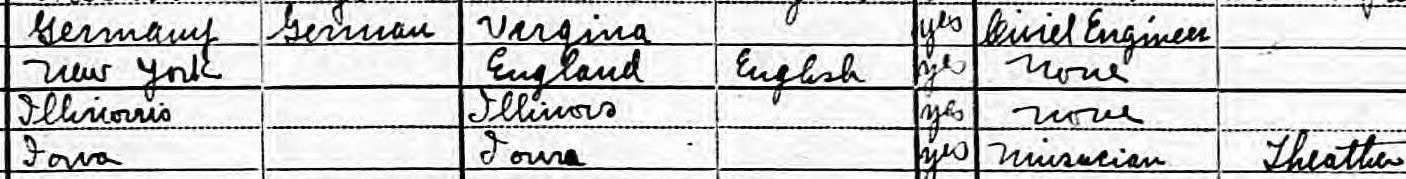

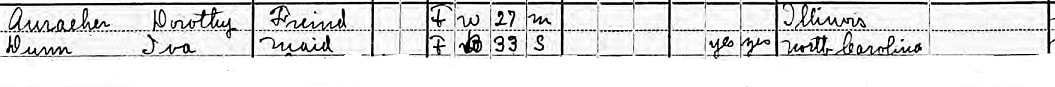

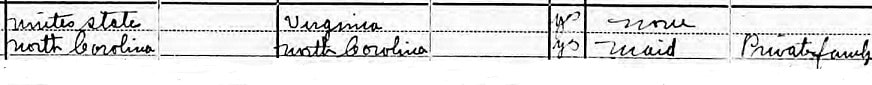

A January 12, 1920 U.S. Federal Census record reveals that Harry Auracher (34), musician in the theater industry, and wife Dorothy (27) were staying with friends in Manhattan. The Aurachers' trip to Manhattan was not just a social visit. The Frivolities of 1920

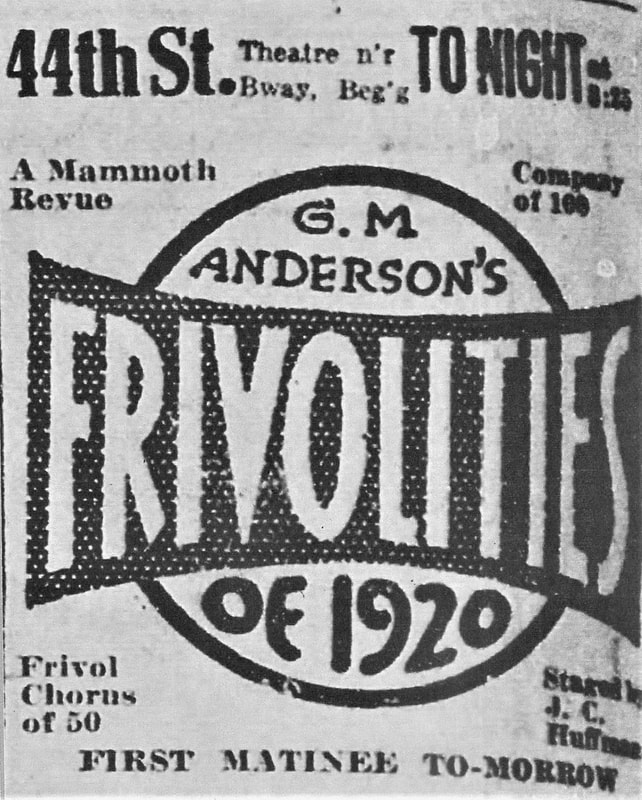

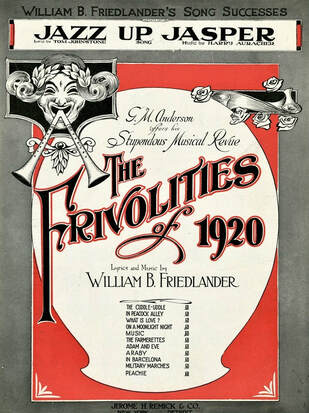

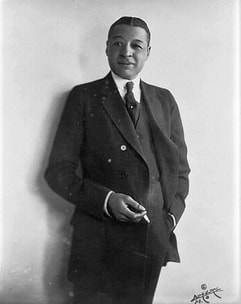

Reviews focused on the show’s vulgarity, its girls, and the likelihood of its success, not on its music. The “Frivolities” is just a gigantic revue that is built up of vaudeville specialties with a big chorus and number here and there through it. There isn’t any attempt at any kind of a story and so it must be judged entirely from revue standards. As such, all that it needs is a little more comedy and some cutting and speeding here and there to make it a sure-fire for the box office. --Variety There is plenty of life in The Frivolities of 1920, produced last night by G. M. Anderson at the 44th Street Theater. Much of it is low life, but it is all lively. There used to be a decided difference between the burlesque show and the Broadway revue, and the difference was more than one of mere costliness of production. That difference seems to be disappearing. The Frivolities of 1920 is really a very expensive burlesque entertainment. Our guess is that it will prove a great success. . . . Frivolities of 1920, presented last night at the Forty-fourth Street Theatre, is big enough and noisy enough for that capacious playhouse, and has a lot of fun and activity. It is lucky the theater is roomy, for some of the revue needs the air. Had Mr. Anderson been as spendthrift and energetic in providing expert showmanship and an atmosphere of good taste he would have an entertainment which might divert a part of the golden stream pouring into the Follies. Frivolities of 1920 would run at the 44th Street Theatre through February and then go on tour. A few days after Frivolities' opening night, an advertisement in Evanston, Illinois’ Daily Northwestern attested to Auracher’s entrepreneurial success. With several orchestras to his credit, Auracher was now president with his own business agent to handle bookings. Despite Harry Auracher's success back home in Chicago, to garner attention and achieve comparable success in the musical theater world, he would need to do something different than Frivolities. First Known Recording of an Archer Tune

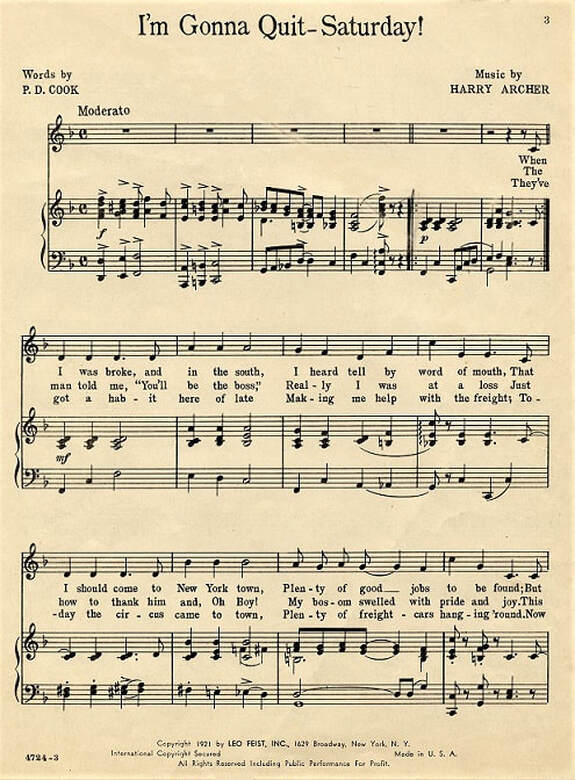

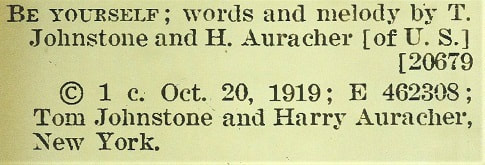

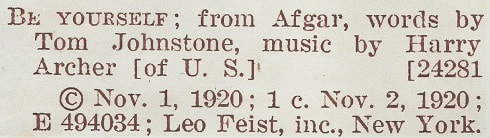

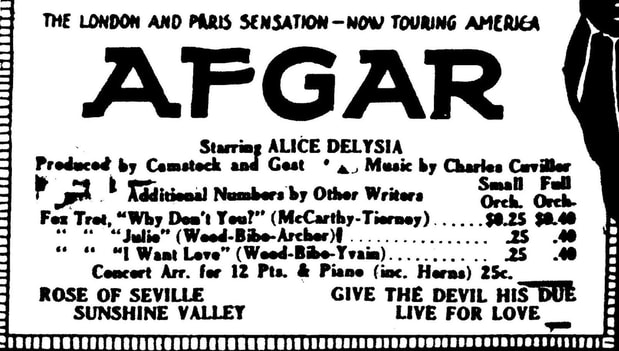

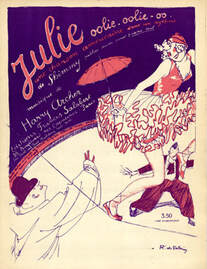

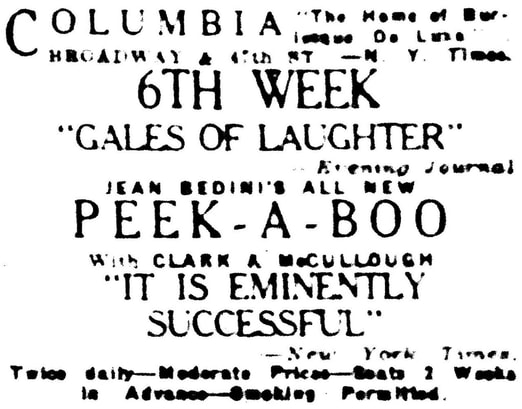

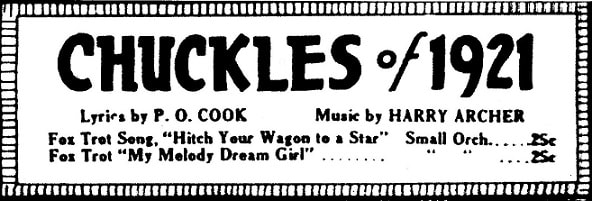

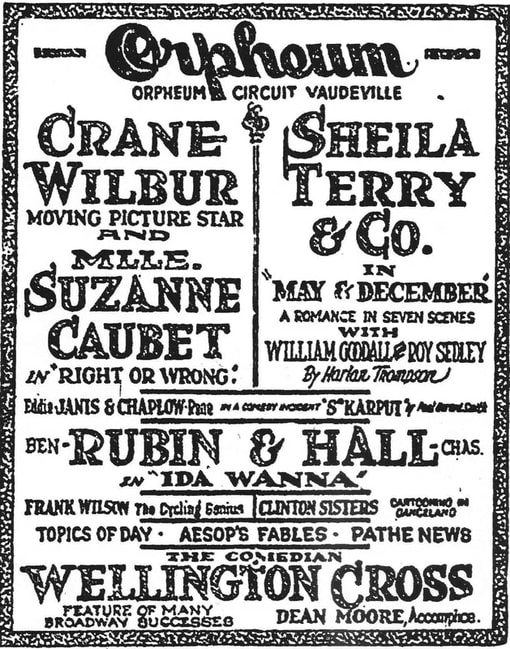

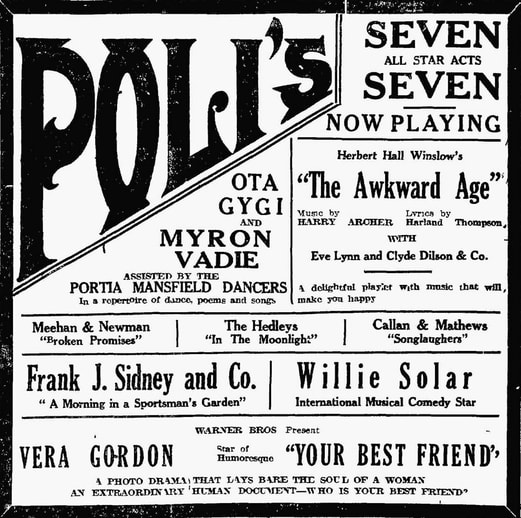

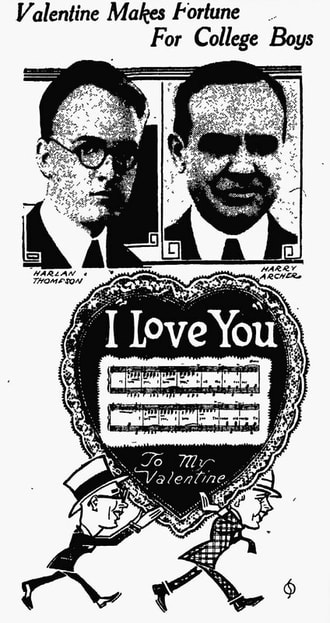

A Career Move, a Name Change, and Minor Shows According to sources to be revealed later, Auracher relocated to New York in February 1920 to join the staff at Feist Music. Aside from a series of Feist publications, I have found no information pertaining to his work for the firm. Pitter Patter and Afgar, 1920 Auracher was soon music director for another William B. Friedlander show, Pitter Patter, which opened at the Longacre Theatre on September 28, 1920, and closed on New Year's Day, 1921. He does not appear to have composed any of the show's music. In November, Feist copyrighted Johnstone and Auracher's "Be Yourself," a piece the pair must have considered for the 1919 show Love for Sale., They had first copyrighted it in lyric and melody form while similarly copyrighting other songs eventually harmonized and re-copyrighted with the Love for Sale show title. Unlike those other songs, "Be Yourself" had no second copyright until designated for the American production of an older French operetta titled Afgar. The show had opened in England in 1919 and was scheduled to open in the U.S. in 1920. This proved to be more than a completed, re-purposed song. Ironically, the second "Be Yourself" copyright marked the Americanization of Harry Auracher's German surname, a new identity for the composer. Harry Auracher became Harry Archer. Peek-a-Boo, 1921 Harry Archer also served as music director for Peek-a-Boo, an elaborate burlesque show produced by Jean Bedini at the Columbia Theatre. Archer teamed up with lyricist P. D. Cook to write the music. Six weeks before the show opened, a brief promotional item in Variety pointed out a theatrical "first": “[F]or the first time in the history of burlesque, the production music will be sold in the lobby and in music stores as with regular Broadway musical shows.” Opening May 16 for the "summer" season, Peek-a-Boo ran until July 2, the date that several theaters closed for the summer. The Columbia reopened in September for its regular season with Peek-a-Boo running twice daily for its first week. Among the show's performers drawn from vaudeville, the Seven Musical Spillers are probably best known today, at least by readers of Ed Berlin's Scott Joplin biography, King of Ragtime. From the outset, Peek-a-Boo received better reviews than most shows of its type and, unlike many burlesque shows, was viewed as appropriate for women and children. Variety commented on the music and expressed its opinion that Bedini should retain Archer for future shows: Other than the pop songs in the specialties, there is a specially written score, with “Hitch Your Wagon to a Star” quite melodious as the theme number. “Melody Dream Girl” is another fetching strain with a production end, various girls singing old songs as they are sent out to about the third row in the orchestra on what looks to be a duplex crane arrangement. This number is extremely well gowned. The Columbia can justly claim that Peek-A-Boo is the best laughing shown on Broadway, and at $1.50 Bedini can justly claim he has the best burlesque show ever turned out. . . . At any other Broadway house it could get $2.50, with just as many if no more laughs. The New York Tribune described Peek-a-Boo as “a succession of ingenious stunts that make up a good show, well received” and added that it ranged “from the regular burlesque joke stuff to a doll fantasy that verges on the classical ballet.” The Tribune further took note of the show's jazz band. In one particularly unusual musical stunt, an alleged Italian from the Shipyards charged down the aisle and into the orchestra staging a fight before returning to the stage to “dance, sing and play several instruments with equal facility and agility.” As we will see later, this may have been one of Harry Archer’s early efforts to make musicians a part of the show rather than confining them to the pit. Feist again published the music, which also included not only "Hitch Your Wagon to a Star" and "Melody Dream Girl," but also "Cuddle" and "Ornamental Oriental Land." Following its run at the Columbia, newspapers from several cities indicate that Peek-a-Boo toured under the new name Chuckles of 1921. May and December and The Awkward Age, 1921-1923 By late 1921, Archer begun collaborating with Harlan Thompson. A former Kansas City Star journalist born in Hannibal, Missouri, Thompson had landed in New York City after serving in World War I. Although he worked at the New York World, Thompson's heart was in the theater where he dreamed of making a living. According to the March 5, 1922 Kansas City Star, Thompson was “devoting all his time to writing for the stage," and had several “playlets” touring on the circuits, including Indoor Sports, Broke, and May and December. Five years later, the New York Times explained that William B. Friedlander had first introduced Thompson to Archer in Friedlander's office. That introduction had led to their collaboration on May and December, which had opened at Poli's Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut, in late 1921 before going on the United Booking Office (U.B.O.) circuit.

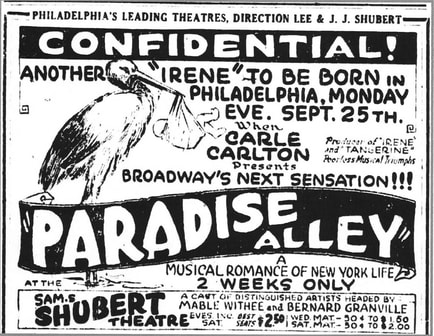

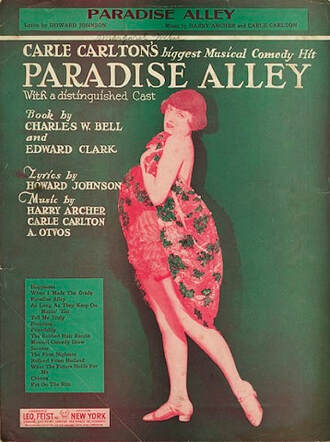

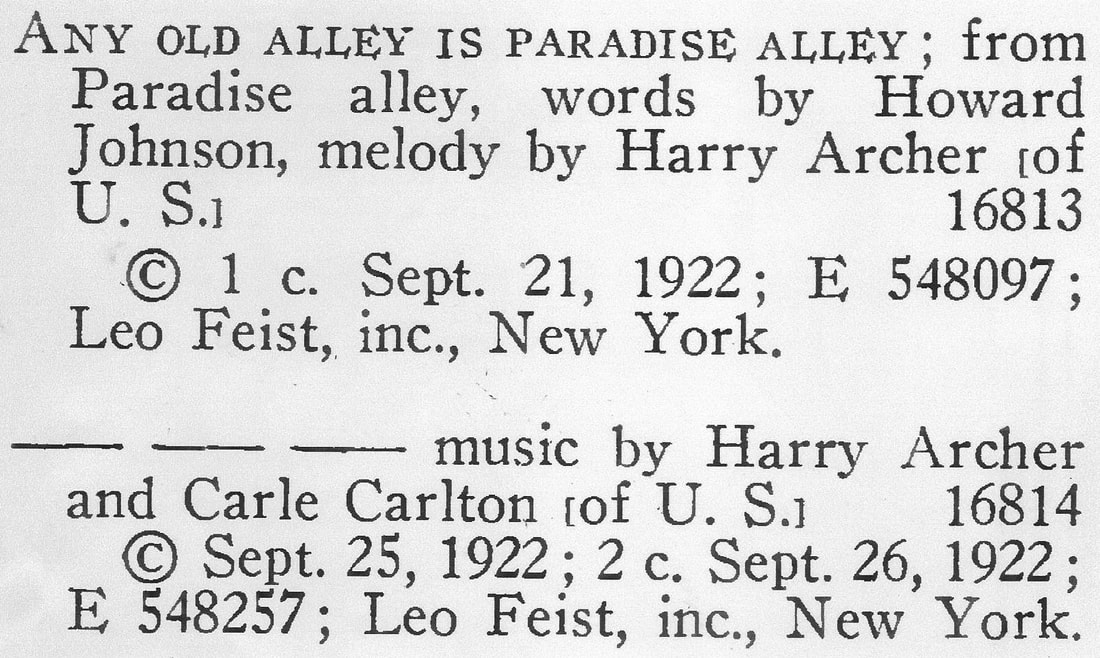

The Awkward Age ran concurrently although separately. With book by Herbert H. Winslow, lyrics by Harlan Thompson, and music by Harry Archer, The Awkward Age starred legitimate theater’s Eve Lynn and Clyde Dilson. Lyrics and dialogue focused on adolescence and told of “Hopes, disappointments and the lights and shades of a boy, a girl, and a mother.” Since both short plays appeared as individual acts in multi-act vaudeville shows, they received little attention. However, Thompson-Archer collaboration, although seemingly trivial, would eventually lead to Broadway success. Paradise Alley, 1922 and 1924 That time had not yet come. Archer was a busy man with another theater project underway or soon underway. On August 15, 1922, the New York Times announced the previous day's opening rehearsal for Paradise Alley, a new show featuring Archer's music. Written by Carle Carlton, a former British band leader who had penned the recent hit Irene, Paradise Alley told the rags to riches story of two young East Side New Yorkers, one who rose to fame in the British theater and the other in the boxing ring. The boxer wanted his girl friend to sacrifice the stage for him, and she wanted him to walk away from the ring to join her in the theater.

The day after its Philadelphia opening, the Evening Public Ledger commented, "Paradise Alley does not appear to be another Irene, even though Mabel Withee does impart to the heroine's role a great deal of charm and some real acting." The main problem, according to the reviewer, was that the show's excessive sentiment "drowned out the comedy, and that's the element that's needed": Stories of New York tenement heroines who aspire to the stage but finally return to their prize fighting sweethearts are all very well, but they should be done in moderation. Paradise Alley is all sweetness and love. The songs are spoiled by the same token. Only Franklyn Farnum, with some nifty dancing, got away from the general spirit of "tell it with loves songs." Due to low box office receipts during the Philadelphia tryout, the show temporarily folded. Carlton did not give up on the show. He hired Clare Kummer, said to specialize in wit, to trim the show "up with sparkles." In March 1924, the revised Paradise Alley opened in Brooklyn.

Following Paradise Alley's Broadway debut at the Casino, Burns Mantle wrote a relatively positive review in the New York Daily News. After observing that musical theater has a set formula but that the "mixing of the ingredients is important," he complimented Carleton for handling that task well. He then added: The music has rhythm and melody. The name song, "Paradise Alley," seeming good for a hit. A professional quartet helps the singing a lot. Dorothy Dyrenforth Auracher Sues for Divorce Shortly after The Awkward Age opened and before rehearsals for the original version of Paradise Alley, Harry Archer's wife in Illinois sued for divorce. On April 28, 1922, the Chicago Tribune carried the story:

An article reporting Harry's denial of her allegations also pinpoints the month of the alleged desertion--February 1920: Neither article gets the 1912 marriage date right, but that reporting Harry Archer's denial appears to pinpoint the month and year he moved to New York to began work at Feist.

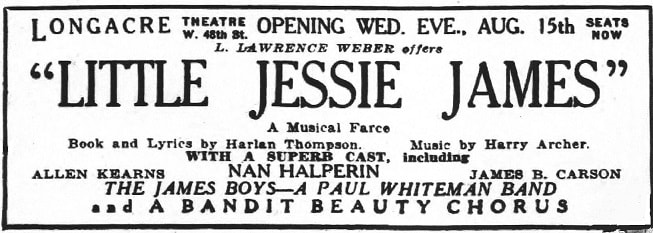

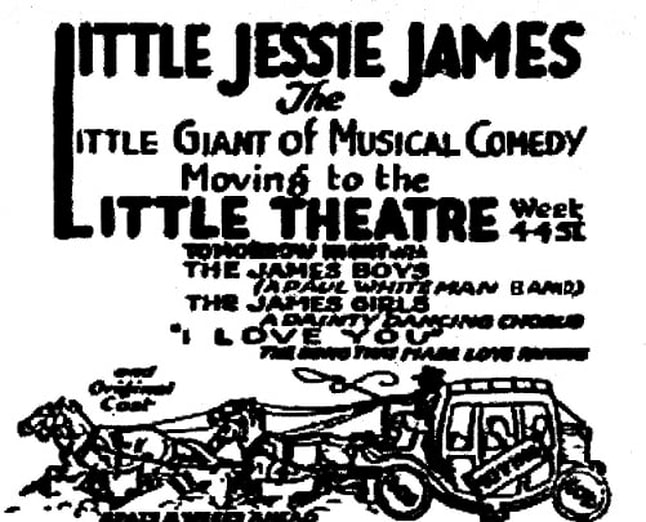

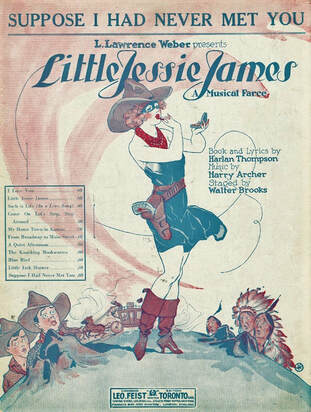

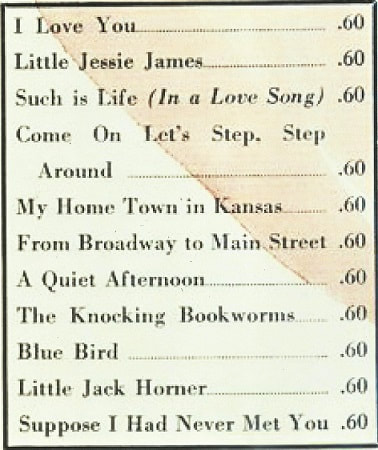

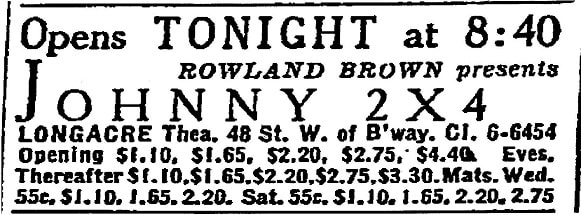

Two other newspaper items raise a question about the accuracy of Dorothy Dyrenforth’s claims: On July 24, 1921, The Daily Star (Queens Borough, NY) printed this small item: “Mr. and Mrs. Harry Auracher of Manhattan have leased the Ferry house on Third street for July and August.” Were the Aurachers living together during summer 1921, well over a year after Dorothy said Harry had deserted her? On April 4, 1923, the Chicago Tribune reported that “Mrs. D. D. Auracher of New York will be the matron of honor” at the wedding of her sister Miss Carroll Dyrenforth, Evanston, Illinois. What was she doing living in New York in April 1923 before traveling home for her sister's wedding? The 1922 article reporting her filing for divorce had said she was living with her Illinois parents. Perhaps Harry did desert Dorothy. Perhaps the two had attempted reconciliation and failed. Perhaps Dorothy didn't want to trade the Chicago area where a socialite for New York where she was not. Whatever the case, newspapers don't provide a clear story. Archer and Paul Whiteman Shortly after the announcement that Dorothy Dyrenforth Auracher would leave New York to serve as matron of honor at her sister's wedding, Harry Archer was temporarily leaving the country in pursuit of his music career. While Paul Whiteman’s Leviathan Orchestra was booked for United States Shipping Board liners during the summer of 1923, Whiteman provided another orchestra, including Harry Archer, to embark on the U.S liner George Washington, April 14. Ship records documenting Archer’s May 11 return to New York from Bremerhaven, Germany, still aboard the George Washington, include a notation that musicians were to be paid upon return. Disembarkation did not end Archer’s association with Whiteman musicians. Thompson-Archer Broadway Shows Prior to joining Whiteman's orchestra as pianist, Archer had teamed up again with lyricist Harlan Thompson with whom he had collaborated on May and December and The Awkward Age. The pair's new project was a full-length musical comedy. Archer returned from Europe to the news that rehearsals would open in two days. Little Jessie James, 1923-1924 On July 12, 1923, while Little Jessie James was in rehearsals, Variety announced the show's opening in New Jersey: Little Jessie James, the musical show which William Friedlander and L. Lawrence Weber are producing, will open at Long Branch Monday with Nan Halperin featured. The book is by Harlan Thompson of the New York World, the score being composed by Harry Archer, first pianist for Paul Whiteman. --Variety, July 12,1923 At the end of July, to promote the show's impending New York City opening, the New York Morning Telegraph reported that Little Jessie James “broke all records on the New Jersey shore.” Little Jessie James opened at the Longacre Theatre on August 15, 1923 and ran there until January 27, 1924, when it moved to the Little Theatre, opening the next day and not closing until July 19.

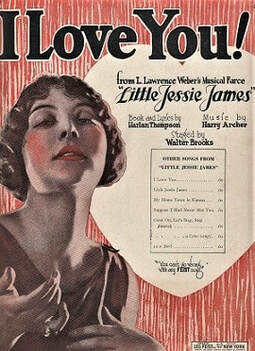

Somewhat like Archer and Thompson, born in small town Iowa and Missouri, the show's main character, Jessie Jamieson, left her Kansas home bound for New York City. Nicknamed for the outlaw because of her history ignoring strict laws back home, Little Jessie James was not making a career move, but instead out for a good time. In New York, she falls into a series of madcap misadventures that include a Murphy bed said to fold into the wall when it shouldn't and unfold when it shouldn't. What looks like big trouble for Little Jessie James naturally works out for the best, and the show ends with her return to Kansas. The music in earlier shows had received little attention. Although Little Jessie James' plot and its chorus girls' beauty continued to fill the majority of the newspaper space dedicated to the show, the show's music attracted substantially more notice than before. This held true from the rehearsal period through the national tour: A number of novelties are promised. Among them is a Paul Whiteman band called the “James Boys.” Special provision is being made to accommodate the 17 musicians in the pit of the Longacre, New York, where the show is due about the first of August. A 15-minute concert prior to each performance and during the 10-minute intermission between acts is part of the “James Boys” duties. --Variety, July 12, 1923

Harry Archer, composer of the music of L. Lawrence Weber's Little Jessie James, now at the Little Theatre here and the Garrick Theatre, in Chicago, and who wrote "I Love You" said to be the biggest song sensation in recent years, has gone back to the scenes of his early triumphs--Chicago--to show the natives how a real, honest-to-goodness successful composer looks. --The Evening Telegram, New York City, Mar. 16, 1924 The song successes of Little Jessie James are too numerous to mention. Everywhere music is played you hear its haunting strains and the song that made love famous, "I Love You," now has the distinction of being the biggest seller among music buyers the world has ever known. The music from the pen of Harry Archer, we can say without fear of contradiction is the best that has been written since The Prince of Pilsen or The Merry Widow, has been given special attention by Mr. Weber who has engaged a Paul Whiteman band to play Mr. Archer's score during the performance and between acts render a Jazz concert that will fairly rock the theatre from syncopated strains and make the oldest person in the house feel like stepping to the tunes. One of the big song hits in Little Jessie James, "I Love You," swept the country like wildfire and has been translated into thirty-two languages and is now being sung in Chinese besides being on Chinese mechanical records. --The Reading [PA] Times, Sept.1,1924 An enjoyable part of Little Jessie James is furnished by the James boys, so-called, a group of young demon musicians selected and sponsored by the king of jazzland, Paul Whiteman, himself. These boys have the honor of having their names listed on the program together with the instruments each one plays and although they are stationed in the orchestra pit, they are an integral part of the play itself. --The Billings [MT] Gazette, Sept.26, 1924 The Paul Whiteman band, under the able direction of Paul Parnell, shared the honors with the cast. . . . The music by Harry Archer is lovely and all of the numbers have vitality. The air that lingers, the one which the audience hums as it goes cafe or homeward bound is "I Love You." The James Boys, so billed to fit in the story, are in reality one of Paul Whiteman's bands, and one of the best. Talented to a mother's son, the musicians play together like a big symphony orchestra. They play solos, too, every man contributing a specialty. The orchestra is far and away the best part of the show. --The Oregonian, Portland, Oct. 17,1924

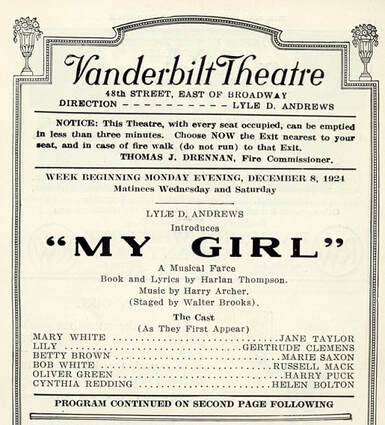

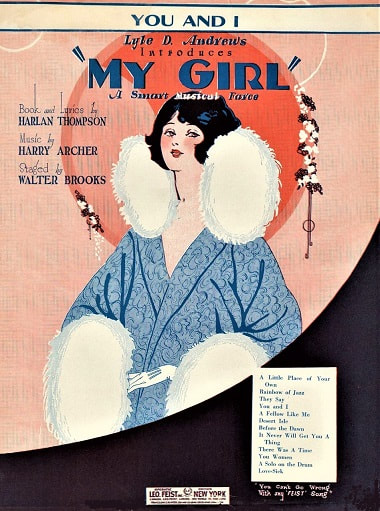

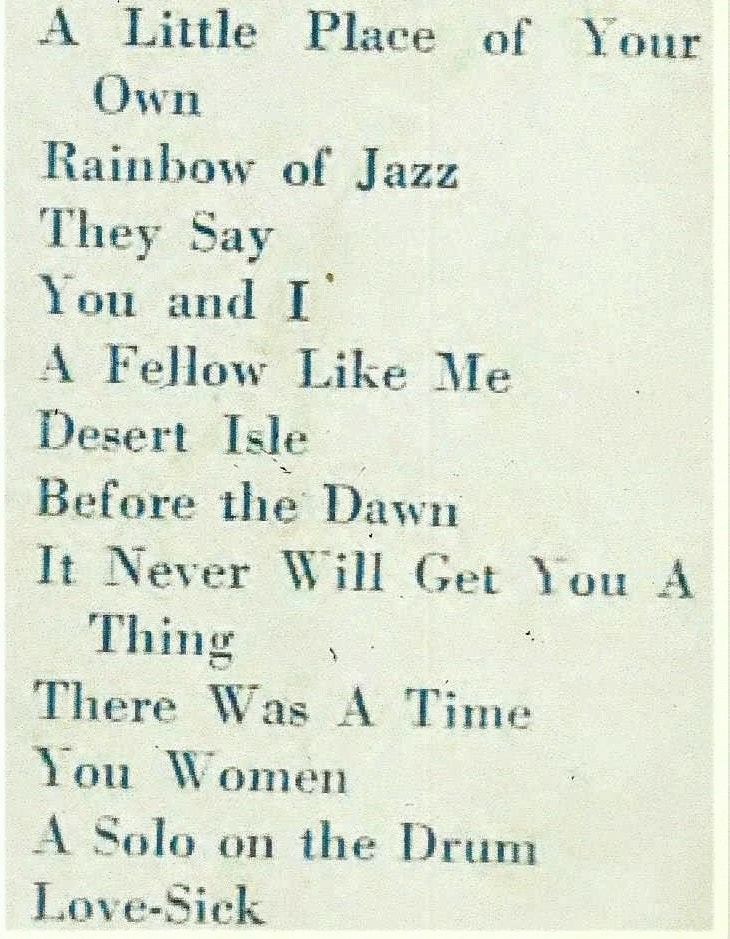

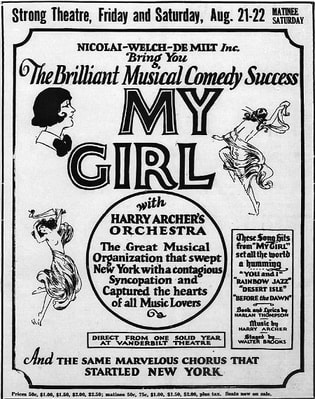

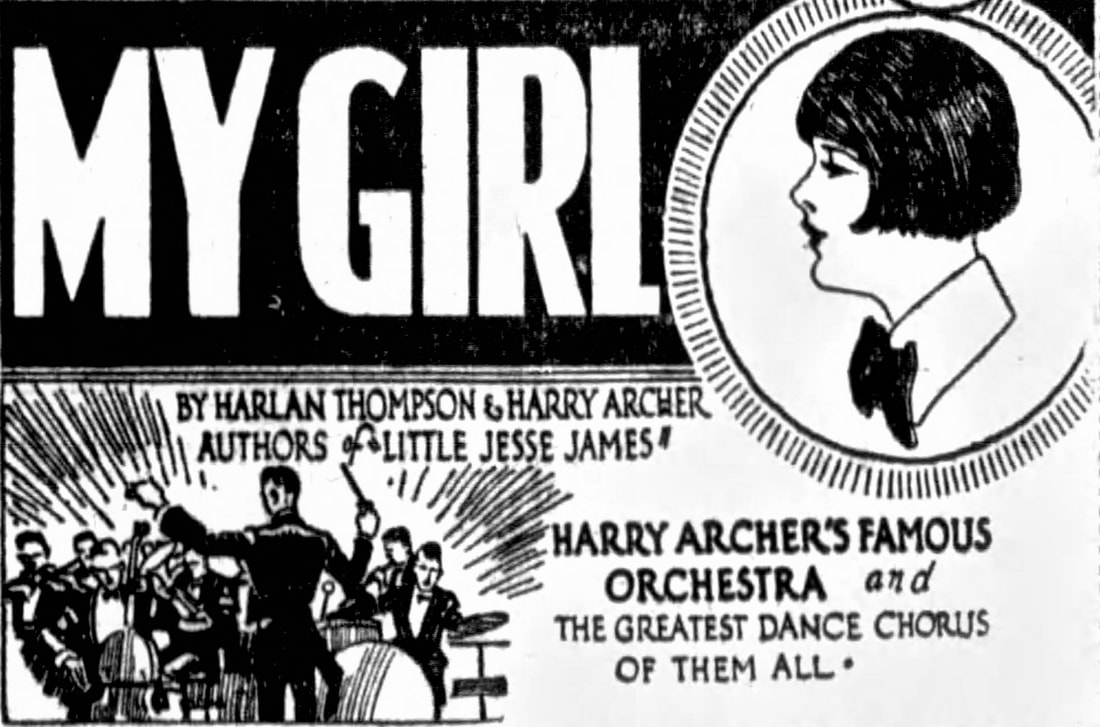

Over the years, several attempts were made to revive Little Jessie James. In late August, 1932, Mount Vernon, New York's Daily Argus reported that Archer played his songs on the piano during a revival at the town's Croton River Playhouse. In November 1943, the New York Times announced producer Walter Brooks' planned January opening of That Girl from Texas, a revised version with new book by Thompson, lyrics by Thompson and Gladys Shelley, and music by Archer. Less than a month later, Brooks canceled the plan, citing inability to clear rights to the production. Two other revivals, under the names Lucky Break (1934) and Heels Together (1942), will appear below. My Girl, 1924-1925

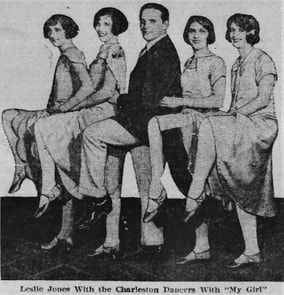

Despite criticizing the thin plot with "a succession of scenes, all leading to nothing," the New York Times reviewer called the show "tuneful and fast-moving, with just enough brightness in it to make you long for more." Elaborating sightly on the "tuneful" side, he noted that "practically all the feet in the audience were set tapping last night" and predicted that Archer's "swinging" rhythms would soon "be danced to all over town." A major change had occurred since Little Jessie James. Harry Archer's orchestra replaced the Paul Whiteman orchestra. Having written a hit with Little Jessie James, Thompson and Archer, nonetheless, had to share much of the credit for the show's success with another man's musicians. A Paul Whiteman Orchestra may have been selected to lend credibility to a show by largely unknown composers. Knowing little or nothing about the supposed young college boy team behind Little Jessie James, many theatergoers may have been enticed to buy tickets to hear the famous orchestra. How prominent the Whiteman group was is unclear, however. Since Archer had returned to New York only two days before Little Jessie James rehearsals had begun, the show's Whiteman musicians quite likely were drawn from the group that had returned with Archer on the George Washington while Whiteman's main orchestra was aboard a different ship. Now that Thompson and Archer had a smash hit on their hands with Little Jessie James, they had reason to believe they could attract a crowd on their own, no longer needing the Whiteman name. While the show ran on Broadway and across the country, publications frequently commented on the Thompson-Archer music and the musicians playing it:

The orchestra in My Girl is one of those tinkley-banjo, moaning-oh-you-red-hot mamma-saxophone and soothing violin affairs, and very enjoyable, too. --The Baltimore Sun, Dec. 21, 1924

Another feature which is most enjoyable in the production is the violin solo by Robert Berne, the conductor of the Harry Archer orchestra. Piano selection will please you, but when you hear the violin, you realize there is no modern instrument to keep pace with this instrument We have only one criticism to make of Mr. Berne and that is that he fails to give an encore. --The News-Leader, Staunton, VA, Oct 16,1925

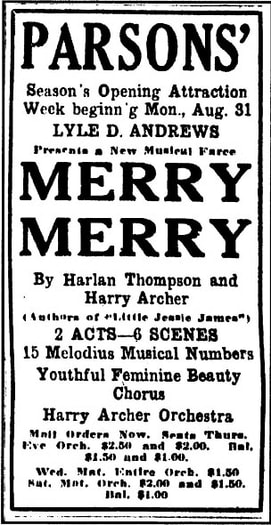

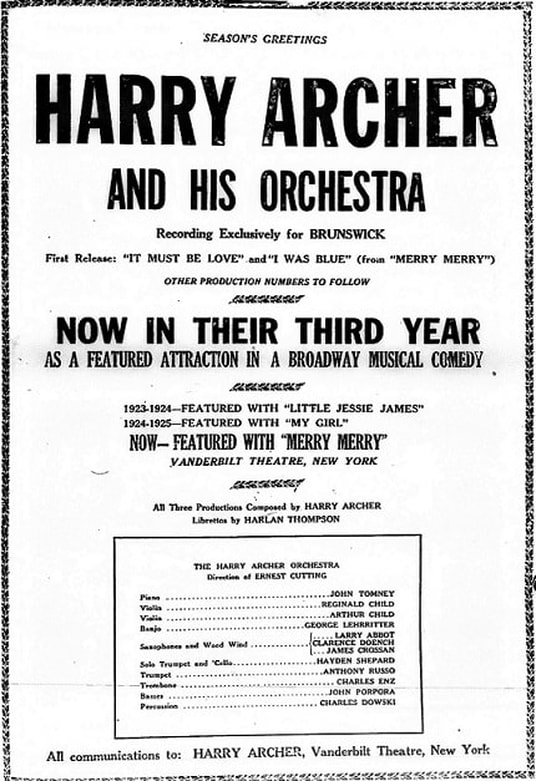

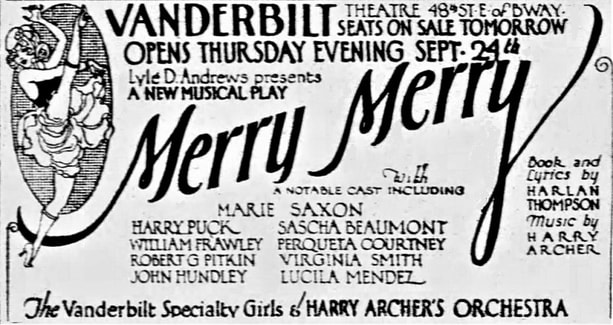

Archer's Contribution to Theater Music. During the Broadway run of My Girl, newspapers noted Archer's innovations. Because some of these had appeared during Little Jessie James, we cannot rule out a possible Whiteman influence, but the inclusion of the Italian shipyard worker on the 1921 Peek-a-Boo stage, who after entering the orchestra pit during a fight scene, began expertly playing several instruments, can just as easily allow us to credit Archer. After discussing Harlan Thompson's innovative small choruses, chosen less for the chorus girls' looks than for their talent and making them capable of assuming small acting roles and advancing their stage careers, a Brooklyn reporter turned to Archer's comparable contributions. Like Thompson who personally selected and trained the chorus girls, Archer did the same for the musicians, becoming "their best friend, if also their severest critic." Just as Thompson reduced the chorus size, Archer traded the regulation Broadway theater orchestra of eighteen to thirty-two for a "small but select" thirteen-man jazz band comprised of musicians capable of playing several instruments and gave them the chance to solo on at least one during every performance. Supporting the idea that Archer, not Whiteman, deserves credit for these innovations, Harlan Thompson explained: Harry not only composes music but plays on the piano and several brass instruments himself. He got the idea that the usual theater orchestra of strings, French bass, and a harp, wasn't able to keep up with modern music. He thought the new orchestra ought to have a piano, saxophones, banjo and so on like a regular jazz band, and he came from Chicago to peddle his idea up and down Broadway for three years without making a dent. Pointing out to New York readers who may have known Archer only as a theater composer, the New York Sun compared band and orchestra leader Archer's "new type of orchestra" at the Vanderbilt Theatre to Gershwin's new type of music. The Sun also let Archer speak for himself: "Every member of the band is a capable solo performer. Every one was chosen as careful as the members of the cast." Archer continued: The distinctive contribution they are making to the music of the theater is that because they are acting as accompanists to performers they must also double as a legitimate string and wind orchestra as well as a jazz band. Archer then predicted the nature of orchestras to come: The orchestra of the future will undoubtedly be fashioned after the small model I am offering at the Vanderbilt, when it is used in musical comedy. The old theater orchestra has outlived its day. Jazz dominates, and so the orchestra ought to include players who are capable of interpreting both modern music and music typical of the past as well. --quoted in The Sun, Feb. 26, 1925 Merry Merry, 1925-1926 At the Vanderbilt Theatre from September 24, 1925 to March 13, 1926, Thompson and Archer's Merry Merry failed to live up to Little Jessie James or My Girl, yet this play about chorus girls was still a success with its 197 performances and its six-month run. During the opening scene, Adam Winslow and Eve Walters, played by Harry Puck and Marie Saxon, meet in a subway station and feel a mutual attraction. As strangers, they go their separate ways. With comedy based in part on mistaken identity, the simple plot ends with Winslow and Walters reunited at the Vanderbilt Theatre. From the show's trial run in Providence, Rhode Island, through its Broadway run, Thompson and Archer continued attracting attention:

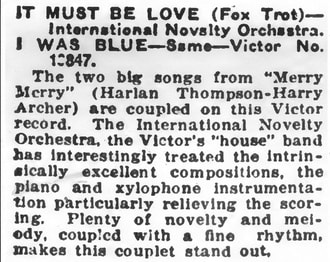

**At the time of this post, titles of "It Must Be Love" and "I Was Blue" are reversed on Internet Archive

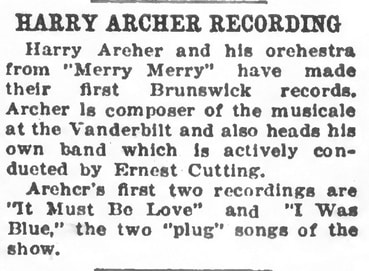

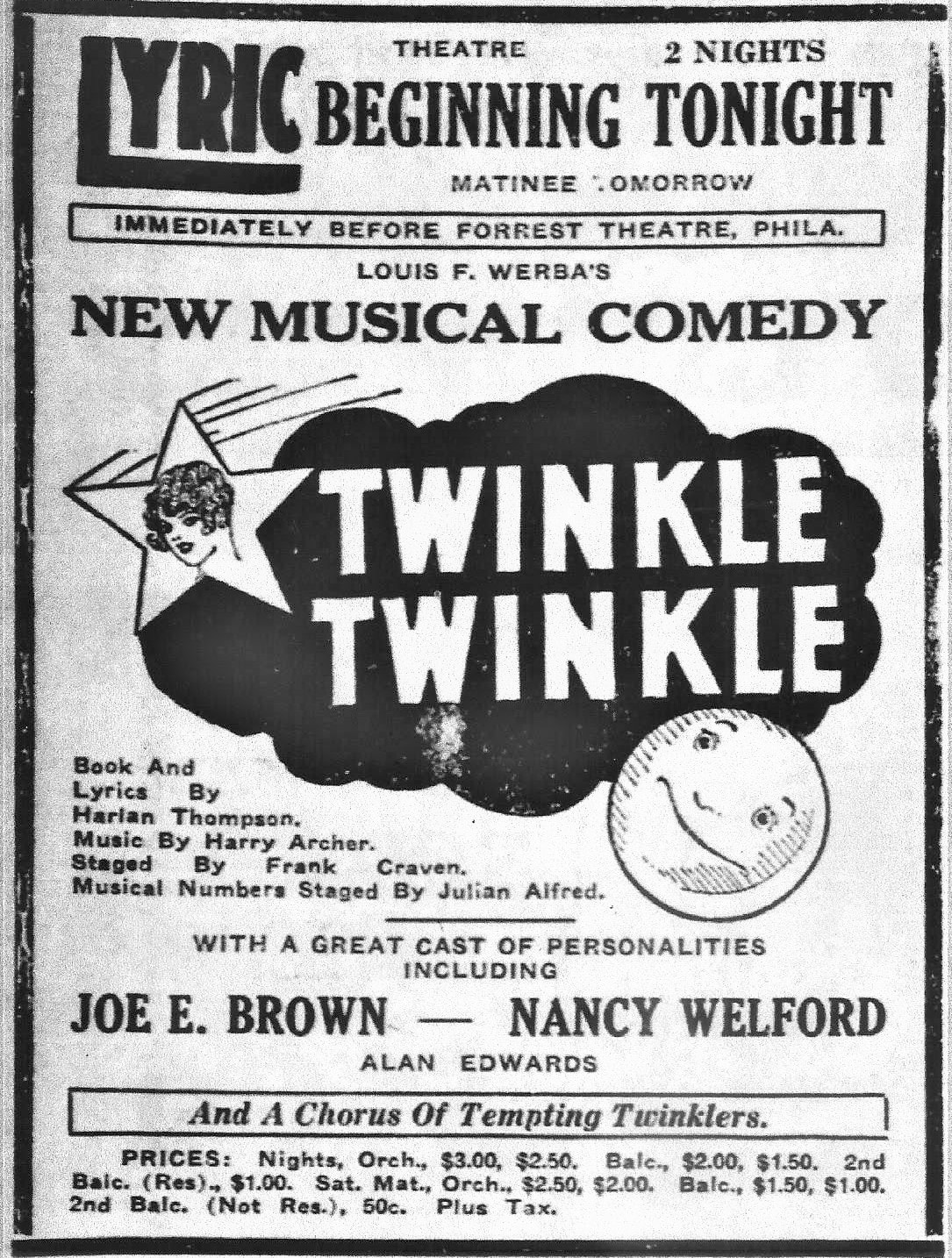

When Merry Merry opened at the Vanderbilt Theater critics were unanimous on one point: the score. Harry Archer, they said, had written music which never fell below the level of excellent at any time. The author of "I Love You" had duplicated his success. He had written "It Must Be Love." --The [NY] Sun, Jan. 20, 1926 Promotional Strategies: A couple months into Merry Merry's Vanderbilt run, the San Diego Evening Tribune revealed that Ruth Varin, Archer's band leader sister, introduced each new Archer piece to that city before anyone else could obtain a copy. When she and her band featured Merry Merry's "It Must Be Love," the Evening Tribune predicted the tune's popularity in San Diego would rival its popularity in New York--long before any road troupe would come that way. Back in New York, an early January issue of The Sun reported that Archer had found another way to carry "It Must Be Love" to wider audiences. Rather than originating the promotional strategy, he had borrowed it from Hungarian operettas in which the producer, composer, and star gave their friends specially-made car horns "so that the hit song may greet the ears of passersby on highways everywhere." Perhaps picked up when Archer traveled to Hungary with Little Jessie James, this was a new twist on that show's powder cases that played "I Love You" whenever a woman opened the lid. When the Vanderbilt scheduled a January French fashion showcase immediately following a Merry Merry matinee, the theater probably drew in new people interested in seeing the latest haute couture. Spectators got not only an eyeful of Paris models strutting the runway clad in spring and summer wear, but also an earful of bonus concert music played by Archer's Vanderbilt Orchestra. Archer's Stories about Composing the Merry Merry Hits. The January 20 Sun reported how Archer, content with completed work, had planned to use his music for "My Own" as the show's main number. Then during a few weeks in Norwalk, Connecticut finalizing the music for Merry Merry, Archer spent eight hours a day at the piano. "One day the arrangement of 'It Must Be Love' chorus played itself. After replaying the chorus and replaying it the next day for Feist's arranger, Archer realized he "had a hit." Unsure what to do because he also liked "My Own," he followed others' advice to make "It Must Be Love" the show's featured number. Archer next explained composing "I Was Blue" while suffering from a severe cold. Feeling bad, he decided to take a day off from working on the show. In the afternoon, a hungry Harlan Thompson came by wanting to eat. Archer who hadn't eaten all day decided that he couldn't let his guest eat alone. Revived and feeling better after a meal, Archer came up with the tune for "I Was Blue." As Thompson wrote the lyric for Archer's tune, he recalled Archer's words: "Funny how that cold took all the music out of me." Just as Archer felt better after eating, Thompson gave his lyric about the blues a happy ending. Whether facts or good stories fabricated by the composers, The Sun concluded, "And that is how the two hits of Merry Merry came into being." Recordings and Radio. During Merry Merry's run, Variety and many newspapers announced Archer's new recording deals with the Brunswick and Vocalion labels, using "Harry Archer and His Orchestra" on Brunswick and "The Vanderbilt Orchestra" on Vocalion. According to the January 27, 1926 issue of Variety, demand had increased for show song recordings, especially in parts of the country that would need to wait a season before a show reached them from New York or Chicago. First up were Archer's hits from Merry Merry: Other recordings quickly followed, Links to some appear on this page. Also in January, Thompson and Archer's previous show, My Girl, was playing at Buffalo and Archer's Vanderbilt Theatre Orchestra appeared on WMAK radio for three evenings, directed by Paul Parnell. Indicating that the chance to hear the orchestra from one's home was not a substitute for going to the theater, the Buffalo Times played up the orchestra's benevolent side. Thanks to the free radio concert, Invalids, the elderly, and their caretakers, as well as young mothers "unwilling to leave their infants alone," could now hear the latest tunes played by "real stage artists whose previous radio concerts have been nothing if not 'wows.'" In early February, Harry Archer and Harlan Thompson appeared together on New York's WGBS for a half hour interview, followed by a Vanderbilt Dance Orchestra performance. The pair's successes had opened many doors. Twinkle Twinkle (1926-1927) Of Thompson and Archer's three Vanderbilt Theatre shows, Little Jessie James was decidedly the biggest hit. Merry Merry, which the New York Times declared three times better than the others, had the shortest run--more than a hundred fewer performances that My Girl and more than two hundred fewer than Little Jessie James. Their fourth musical comedy, Twinkle Twinkle, opened at the Liberty Theatre, not the Vanderbilt, on November 16, 1926, and closed on April 9, 1927, with a total of 167 performances. With nearly a five-month run, no one could call the show a flop. Nonetheless, Twinkle Twinkle would be the last of the major Thompson-Archer collaborations although not their last collaboration. The dramatic setting changed from the pair's usual New York City to a train traveling through Kansas and to the fictional town of Pleasantville. Instead of a Midwesterner arriving in New York, a glamorous actress escapes her private car and seeks anonymity in Middle America. Leaving the screen for the small-town restaurant, she falls for a local newspaper reporter, never suspecting that he also has a hidden identity as the vice president of the John W. Whoozis Film Company in town scouting a location for a million-dollar theater. Meanwhile, responding to rumors that a famous film star is in town, the correspondence school-trained private investigator determines to find her and repeatedly dons ridiculous disguises in the attempt to discover her identity. Given Thompson's birth in Hannibal, Missouri and Archer's in Creston, Iowa, the pair's frequent use of Midwestern characters or now a Midwestern town makes sense. The contrasting life styles provided comedic opportunities. Touring show troupes might also have reaped good profits in Midwestern communities, even in any small town or city far from New York.

In American Musical Theatre" A Chronicle, Gerald Bordman points out that due to weaknesses in the book and score Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby were asked to contribute additional music. The opening of the New York Times review refers to "additional scenes, lyrics and music." Before the show opened at Broadway's Liberty Theatre, Kalmar-Ruby had added "We're on the Map," "Sweeter than You," and "Whistle." Two Thompson-Archer songs from the list above had vanished and new Thompson -Archer tunes added. Again referring to "the none too substantial plot," the New York Times accepted that characteristic as common to musical comedy and, overall, complimented the show:

The Times reviewer opened the paragraph with "Possibly the most damning thing that can be said of this new musical comedy is that it is clean." Perhaps that remark explains the earlier "a little less intimate" comparison between this show and the three Vanderbilt Theatre shows which had sometimes been described as off-color. In fact, because of Little Jessie James' disappearing Murphy bed scenes, London had initially banned the show but later lifted the ban. During the New York run of Twinkle Twinkle, the Chicago Tribune granted that the show "has most of the things a music play needs." Yet the paper was far from complimentary unless calling Thompson and Archer "practical workers" might be construed as a compliment. The Tribune appears to have been making the point that Thompson and Archer wrote whatever would line their pockets: The Messrs. Harlan Thompson, who used to write pieces for the World newspaper, and Harry Archer, who used to compose tunes for any publishing house that would buy them are practical workers in their field. They write for the trade and their present ambition, I gather, is to give the trade what it will pay for. Hence the production of a week ago of another of those things with music called Twinkle Twinkle. --Dec. 5, 1926 Following the road show's Chicago opening at the Erlanger Theater, the Tribune commented somewhat more specifically on the music:

The San Francisco Examiner viewed the music, as performed by the chorus, at least somewhat more favorably, describing it as one component of a successful show: All are equipped with legs and voices that don't find it difficult to sing to Harry Archer's music, which is tuneful and xylophony--as in Little Jessie James. And the chorus, very dressy in silks and frills, impinges happily on the eye. The episodes are well framed, too. . . . In addition to the recordings, Archer or the show producers found another way to plug the show and its music. On December 10, 1926--less than a month after the show had opened, WEAF radio announced that the Twinkle Twinkle stars and orchestra would broadcast a "tabloid version" of the show at 6:45 that evening. During the musical comedy's 21st week (late March), WGBS similarly announced that after the evening's performance, the entire cast and orchestra would broadcast a "midnight air version" The Show Folds in New York and on Tour. Despite such efforts, Twinkle Twinkle folded in New York approximately a week and a half later but lived on for a few months on the circuit. The El Paso Evening Post reported on the show's final performance, December 3, 1927, with the orchestra "playing in jazz" Auld Lang Syne. Some of the performers returned to New York; others reportedly joined another show in Los Angeles. Star Joe E. Brown, the correspondence school detective, was said to be going to L.A. "to have a tryout in the movies." Harlan Thompson joined those headed to California where he continued his career as film writer, lyricist, director, and producer. Despite his new ventures, Thompson didn't entirely abandon his interest in musical theater.

Legal Troubles and a Second Marriage

A Breach of Promise Suit Basing the headline on Archer's hit song from Little Jessie James, the Daily News opened its article about a lawsuit by quoting the song's chorus: "I love youoooooo The Daily News went on to explain Hattye Fox's reason for suing Archer for breech of promise and $100,000. According to Fox, she had met Harry Auracher in July 1919 when she was in the cast of Love for Sale. Still married and living in Chicago, Auracher had allegedly struck up a relationship with Fox, and "less than a year after that, Archer [as he was by then calling himself] promised to make Hattye his wife." Fox states that Archer asked her to retire from the stage "to do housekeeping" for him. When Archer composed the music for Little Jessie James, she explains that his "interest in her began to wane" and that he left her when the show and "I Love You" became hits. Not until February 1924 [the month during which Dorothy and Harry Auracher's divorce was finalized, did Hattye Fox say she had learned Auracher was married while she was living with him. In late November, 1927, the New York Times reported that Fox's breach of promise suit was still pending in West Chester County courts. Furthermore, Fox was now also suing Archer for what she claimed was her share of the profits for songs she alleged she co-wrote during her time living with Archer: "I Love You" and "You Know What I Know" from Little Jessie James, "You and I" from My Girl, "It Must Be Love" from Merry Merry, and others from Twinkle Twinkle and Afgar. When Archer's lawyer called Fox a "gold digger" during a change of venue hearing, her lawyer argued, "She is a sweet, little girl and as pretty as her aunt," the actress Della Fox. In June 1928, the Times reported that Fox's second suit demanded 50% of the song royalties from 1919 to 1924 and that Archer had proposed a settlement out of court for an undisclosed amount. Although I haven't located further information regarding these suits, Fox was far from the "sweet little girl" her lawyer wanted the judge to believe she was. For one thing, she was not "a little girl." Born in 1888, she was only two years Archer's junior, making her approximately 31 when she met Archer in 1919 and 32 when she moved in with him in 1920. Second, no mention was made of her 1914 St.Louis divorce from singer and former Steward Opera Company Manager William G. Stewart on the grounds of desertion. Fox and Steward had known each other since at least 1904 when they performed together is the show Louisiana, written for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, more commonly known as the St. Louis World's Fair. Ancestry.com provides Fox and Stewart's 1907 New Jersey marriage record. Finally, less innocent and naive as she must have portrayed herself, Fox was a highly experienced performer when she met Archer, not an upstart chorus girl. Marriage to Alma Lescher

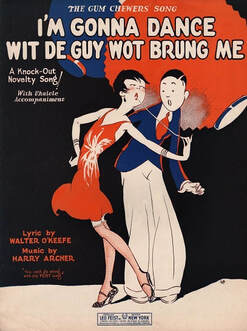

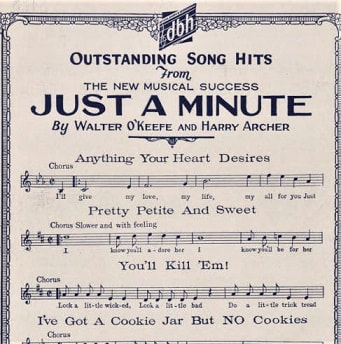

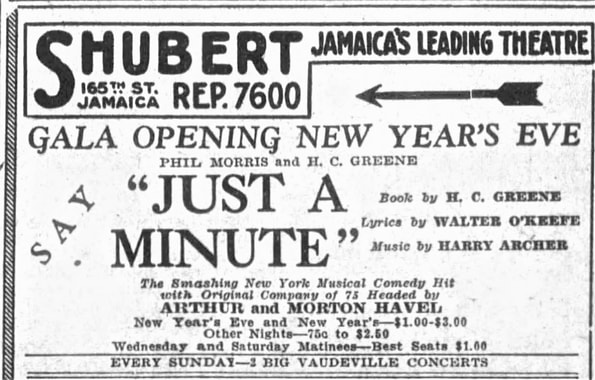

Alma also authored or was the subject of many other articles during her marriage to Harry Archer Her 1988 obituary reported her "interviewing Hitler, drinking with Hemingway in Paris, and sailing with James Joyce,"--all during the height of her career in the '30s. Archer's Views on Broadway and the Little Theater Movement In 1927, syndicated columnist Lemuel F. Parton, who sought out interesting people to feature in his columns, interviewed Harry Archer. The result was an article focusing on Archer's views about Broadway and the role he felt the Midwest, West, and South should play in determining the future of the American theater. Describing Archer as "the inevitable successor to Victor Herbert in the musical world," Parton praised Archer's musical comedy successes. He explained that Archer rejected Easterner H. L. Mencken's view that the rest of the country was a "cultural wasteland." Parton quoted Archer's opinion that other parts of the country were leaving Broadway behind: The trouble with Broadway is that it is behind the times. While America as a whole has been growing up and maturing in the arts, Broadway has been standing still. There is a healthy little theater movement springing up all over America; there is new creative vitality in music and there is evidence everywhere of the beginnings of native drama and music far more worthwhile than the old Broadway output--consisting mostly of a mob of girls, to which the makeshift books and lyrics are entirely secondary. --The [Omaha] World Herald, July 26, 1927 After filling in Archer's biographical and theater background, Parton again let the musician speak for himself: For the first time in its history, America at large is becoming intelligently critical in the fields of literature, music and drama. The best work of the future will be done by men who are essentially American and who are not dazzled by mere sophistication or by the smart and flippant currencies of metropolitan taste. I do not wish to belittle much splendid work now being done by Broadway producers, but I do want to insist that the end is at hand for the sleazy, commonplace productions, barren of taste or intelligence and rigged out with the old banalities of underdressed girls and third-rate music. Archer predicted success throughout the country for the "high class roadshow" and argued that more people had begun occasionally attending the theater due to the successful Little Theater Movement--a non-commercial movement in universities and cities giving playwrights such as Maxwell Anderson, Elmer Rice, and Eugene O'Neill a chance to stage their work. Archer believed that American theater needed "a declaration of independence of Broadway with productions by men who know the west and south, whence many of our best artists come." Had Archer rejected the types of shows for which he'd written music: burlesque, vaudeville, or musical comedies repeatedly described as little more than vaudeville acts strung together by a weak plot? Might his new wife Alma have played a role in his ideas at this time? Was he thinking of the efforts he and Harlan Thompson had made to turn chorus girls into actresses and to make pit orchestras a part of the show? Later Shows Just a Minute, 1928 Again teamed up with vaudevillian and lyricist Walter O'Keefe, Archer next wrote the music for Just a Minute, a show differing somewhat from those before it. According to the Brooklyn Standard Union, Just a Minute was "primarily a musical" but embodied "a revue, a black Harlem cabaret, and a prize fight." During the show's pre-Broadway tryouts, the Boston Globe described it as combining two popular show characteristics: a largely vaudeville act sequence with enough plot to introduce the songs and a story about show business--about a pair of young song writers. For the most part, the Globe praised the production: It begins with an orchestra of pretty girls, under the vivid leadership of Count Berni Vici--and that's no kid--the girls are fine musicians and have been chosen for an unusually perfect ensemble. . . . Just a Minute opened on October 8, 1928, at Broadway's Ambassador Theatre. One of four shows in part dealing with boxing to open on Broadway in a six-week period, Just a Minute more than doubled the performances of two of those shows but fell far short of Hold Everything's 409 performances. Changing part way through its run from the Ambassador to the Century, Just a Minute closed December 15 after 80 performances and then went on the road. The New York Times offered few compliments: Another musical comedy opened last night at the Ambassador Theatre and that is precisely the way in which most of those who saw it are likely to think of it. Perhaps the "Symphonic Girls" could have been Archer's tribute to his sister's San Diego all woman orchestra. But, if so, why have a male conductor? The black cabaret scene, with what Brooklyn's Standard Union called "the riotous folk dances of Africa, as transplanted to Harlem," was a first in a show featuring Archer's music. Yet the show went further, introducing the Ebony Steppers, black chorus girls paralleling the show's white chorus, and "jazz music syncopated by Peek-A-Boo Jimmie and his colored band" paralleling the white women's pit orchestra. Although the show included perhaps daring changes from Archer's norm, it failed to attract the masses. Archer would never again see a hit to approach Little Jessie James although one future London production would surpass Twinkle Twinkle. Daddy, 1928-1929 Little is known about Daddy, an Edmund D'Orsay & Company one-act farce that helped to fill out theater programs between 1928 and 1929. The Springfield [MA] Republican referred to it as "from the fertile pen of Harlan Thompson, with special music by Harry Archer." Another issue of the paper provided a small clue to the comic plot, telling readers that it 'has to do with twins, triplets and possibly quadruplets." The Ottawa [Canada] Journal confirmed that Thompson wrote book and lyrics and commented briefly, but generally, on the play: Edmund D'Orsay and company will be seen on the current bill in a musical farce entitled Daddy. The piece, which was written by Harlan Thompson with music by Harry Archer fairly Because Daddy was little more than a short vaudeville act, newspapers gave it little attention. What it received was probably due to people's familiarity with the Thompson-Archer duo. Keep It Clean, 1929 The day after Keep It Clean opened,, the New York Times classified the show as "a hodge-podge of vaudeville, revue and night club specialties" and judged it "a passable diversion for this time of year," never any better than that at any season. The Times review opened with what may have been the program credits. Other papers provided nearly the same information, sometimes the identical information: Although Alvin Kayton of the Brooklyn Citizen believed that the "music and lyrics slightly surpass[ed] the general level of the show and helped the amusement value a good deal," I've located only three songs from Keep It Clean. Archer wrote one-- "All I Need Is Someone Like You"-- with words by Charles Tobias. Shapiro, Bernstein published all three songs, the other two by Lester Lee, one of those in collaboration with Jack Murray. Given the number of people credited with music and lyrics, other songs must never have been copyrighted. The show was hardly a smash hit: Keep It Clean, which is not altogether clean, is called an "intimate musical revue." Intimate in this instance means incompetent, musical means nothing at all and revue means merely permitting a large number of third-rate performers to do whatever they think best. I was unable to stay through the first performance of Keep It Clean, but from what I saw of it I should say it is successfully geared to meet the demands of those who find the low-caste revues better than no entertainment during the off months of the season. A loud and common show that doesn't pretend to be anything else. Keep It Clean opened June 24 and closed July 6. Shoot the Works, 1931

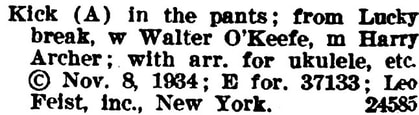

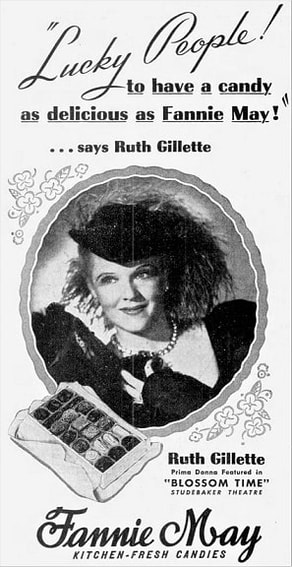

Shoot the Works closed October 3 after 87 performances. Organized as two-week fund-raiser, the show's success meant that performers, who originally agreed to work for free, all began receiving salaries after the first two weeks. Lucky Break, 1934 From fall 1934 until spring 1935, Harry Archer's music was again heard by London theatergoers. Called a revised version of Little Jessie James, which had played in London a decade earlier during its European tour, Lucky Break had a new book and lyrics by Douglas Furber and revised music by Harry Archer. The show's opening date isn't certain. The New York Times and New York Sun indicate that it opened October 2, 1934, each providing a London dateline and the New York Times quoting the London Times' review. However, several days earlier, on September 25, London's The Guardian published a review of Lucky Break's previous night's opening at the city's Palace Theatre. The answer lies in a September 20 advertisement in The Guardian. For whatever reason, Lucky Break had opened at the Palace before its scheduled opening at The Strand. Newspaper accounts reveal little connection between the plots of Little Jessie James and Lucky Break other than the repeated disappearances of characters into an opening and closing Murphy bed in the former and a statement in The Guardian that the latter's action "rests on the appearance and disappearance of most of the characters at the wrong time" through such means as falling down stairs and through trap doors. Likewise, newspapers provide little information about the music aside from the New York Times' statement that Archer had "entirely revised the score." Copyright records bear this out, at least if we can safely assume that new titles mean new music rather than the same music with Furber's new lyrics. New titles included "Am I Delighted," "I'd Like to Know," Tum-Tum-Tum," and "A Kick in the Pants." According to the New York Sun, London's Daily Mail labeled it "delightful" and the Daily Herald "excellent." Listen to three selections from Lucky Break. Although Archer is known to have directed the Little Jessie James orchestra for part of its London run, he may or may not have also directed the Lucky Break orchestra. Although no record can be found of his arrival in London, on November 9, more than a month after the show opened, Archer sailed from Southampton aboard the S. S. Washington, arriving back in the Port of New York on November 15. Lucky Break ran another five months. Based on the advertisement below, we can estimate that the show closed on or around Saturday, March 23, 1935. Carrying the the previous day's London dateline, a November 15, 1934 article published in Territorial Hawaii attests to widespread interest in theater news--at least, of the uncommon sort. The Honolulu Advertiser reported that Harry Craddock, an enterprising American bartender at London's Savoy Bar, had invented a cocktail and named it for one of Archer's "hit musical numbers" from Lucky Break. Whether leaving the show with the tune in one's head or perhaps wanting to relive the experience, one could order a Kick in the Pants--a drink comprised of 1/3 brandy, 1/3 Bacardi rum, 1/6 Cointreau, and 1/6 lime or lemon juice. Entre Nous, 1935 Back in the U.S., Archer may have reused "A Kick in the Pants" with a new lyric, and possibly other Lucky Break tunes, in a new show. Dan Dietz's Off Broadway Musicals, 1910-2007 indicates that Entre Nous opened December 30, 1925, at the Cherry Lane Theatre, Greenwich Village and ran for 47 performances. On December 21, nine days before a possible Cherry Lane Theatre opening, The Daily News told a somewhat different story: "Entre Nous is current at the Provincetown Playhouse, having moved from the Cherry Lane Theatre." A Christmas Day advertisement in the New York Times also placed the production at the Provincetown Playhouse. Possibly the show moved or returned to the Cherry Lane on the 30th. According to Dietz, Entre Nous included not only "A Kick in the Pants," but also "I'll See You Home," "Under My Skin," "A. J.," and "Am I?"--each with music by Archer and lyric by Will B. Johnstone. Unfortunately, I've been unable to locate copyright records for any or these aside from the O'Keefe-Archer "A Kick in the Pants" from Lucky Break. Strip Girl, 1935 The third and final act of Strip Girl contained the show's only song--"I Want a Flame," music by Harry Archer and words by Jill Rainsford, vaudeville and early New York film actress and songwriter. Opening at Longacre Theatre on October 15, 1935, Henry Rosendahl's play, in part, told the tale of of a working stripper and prostitute who had saved $8,000 to send her younger brother to college, only to have him die of cancer and send her to the bottle. The show received a complex review from The Daily News. Despite describing the show's profane elements, critic Burns Mantle refused to condemn the show. Instead, he compared it to Maxwell Anderson and Lawrence Stallings' 1924 What Price Glory?--an anti-war satire set in World War I France. In Strip Girl, the heroine is, as said, the strip tease artist who plays applause-poker with the audience, removing one shred of covering for each salvo of cheers and retiring finally stripped to the buff, but still clothed in her right mind, while the applauding animals out front have lost theirs. . . . We might view Strip Girl as the trashiest show to contain Harry Archer's music, Or, remembering his praise of Little Theater, which launched such playwrights as Maxwell Anderson and Eugene O'Neil, we might view it as the new type of show with which Archer would proudly have claimed association. Johnny 2x4, 1942 The next show to feature Archer's music opened at the Longacre on March 16, 1942 and closed on May 9 after 65 performances. Written by Hollywood gangster-film scriptwriter Rowland Brown, Johnny 2x4 takes place in a speakeasy. Daily News critic Burns Mantle devoted enough space to the setting that readers can almost smell the patrons' sweat and the wet bar towel that "reeked of stale beer." Yet, unlike some critics, Mantle left viewers to make up their own minds, much as he had with Strip Girl: Fortunately the box office reception was better than the press reception and at this writing Johnny 2x4 is promising to continue playing. Along with the "gunmen and their molls" filling the 2x4 Club are honky-tonk pianist and owner Johnny, a fellow musician "who blows a sweet horn" and bumps off a killer, and a singing cigarette girl, each of the three introducing music suited to the Prohibition Era. Unlike Strip Girl, a non-musical that contained only one song (Rainsford and Archer's "I Want a Flame"), Johnny 2x4 was a song-filled "musical melodrama." Archer had composed only one of the show's tunes--"We Were Lucky Together," with words by rising star Gladys Shelley (1911-2003). Heels Together, 1942 A few months after Johnny 2x4 closed, Archer teamed up again with Harlan Thompson, who had written the book for Heels Together, an old-style song-and-dance revue. Archer's collaborator on Johnny 2x4, Gladys Shelley, shared lyrics credit with Thompson. Featuring "a bevy of blondes, who sing, dance, and swing," Heels Together was publicized as a revised Little Jessie James with rewritten book and original songs. Newspapers announced the show's scheduled September 15 opening in Scarsdale, New York, for the last week of the summer season. Next stop Broadway! Four days before the Scarsdale opening, the nearby Dobbs Ferry Register declared half of the dozen songs "certain to find a place on the hit parade before the season is very far advanced": "Wonderful," "Got to Have a Man Around the House," "59th and Fifth," "Ten Minutes Longer in Bed," "How Did You Ever Happen to Me?" and "Who's to Blame?" On December 13, nearly three months after the Scarsdale run, the Miami News published a December 12 wire report from New York listing fourteen new shows scheduled for Broadway debuts before the year's end. The list included Heels Together. A delay in the Broadway opening must have turned into cancellation. I have located little information about Heels Together following this announcement. In the May 23, 1943 Philadelphia Inquirer, former Heels Together leading actress Joan Roberts revealed that the play was still being "revamped for a fling at Broadway." Co-stars Joan Roberts and Lee Dixon left the show. Dixon explained how a composer and lyricist came to Scarsdale scouting possible performers for a new musical (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 10, 1943). They tapped Joan Roberts for the role of a young farm girl living with her aunt and a hired hand and Lee Dixon for the role of a dumb dancing cowboy returning home from the big city to claim his bride. Roberts and Dixon left the floundering Heels Together and achieved stardom as Laurey Williams and Will Parker in Oklahoma! This may have been Heels Together's greatest success. More Marital Changes, 1942 and1946 Archer's life wasn't going particularly well professionally or personally, Third Marriage On February 25, 1946, a Cook County, Illinois marriage license was issued to Harry Archer and wife-to-be #3, actress Ruth Gillette. Newspapers reveal that Archer was currently directing the orchestra during the national tour of Sigmund Romberg's revived Blossom Time. Gilette was playing Bellabruna, one of the show's leading roles. How long Archer and Gillette had known each other is unclear. Both are mentioned in newspapers from the Midwest to the West for five months prior to taking out the license. Blossom Time had opened at least by early October 1945 when it played in Springfield, IL, traveling to such places as Tacoma, WA; Portland, OR, San Francisco, Ogden, UT; Sioux City, IA; and Sioux Falls, SD, before opening in Chicago on February 2, 1946. After closing in Chicago on March 3, the show continued its tour eastward for another few months. Archer easily could have died before marrying Gillette. Following opening night, fires broke out in four locations of Chicago's Congress Hotel. They were later attributed to a grease fire and four room fires. The Chicago Tribune reported the hotel managing director's account of the fire in Archer's room shortly after the grease fire: "We had to break in. We found the guest sitting in a stupor in a morris chair. I'm sure the fire was started by a cigaret the guest dropped. We put him in a room on the third floor of the south building." Archer was one of the lucky ones. Only an hour after employees helped another guest to his room, the third fire broke out there. Firefighters were unable to save him.

Harry Archer's Death A small-town boy from Creston, Iowa, Harry Runkle Auracher had dabbled briefly in ragtime but devoted his career to his Chicago and New York jazz orchestras and to the musical theater, changing his name to Harry Archer along the way. His aspirations outweighed his achievements, but he had his moments of glory, most notably with the hit Broadway show Little Jessie James. One of the original members of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP), Harry Archer died April 23,1960, at New York City’s Doctors Hospital, following a heart attack, and was buried at Ferncliff Cemetery, Hartsdale, Westchester County, New York. He was survived by wife Ruth (1906-1994). Although she appeared in TV sitcoms from time to time into the 1980s, she is probably best known for playing Lillian Russell in The Great Ziegfeld (1936). Recordings of Miscellaneous Archer CompositionsClick each title to hear the recording. Recordings by Harry Archer and His Orchestra Click each title to hear the recording. Two pieces also composed by Archer are marked with an asterisk. Harry Auracher/Archer Compositions 1908 “Love Me” Is All I Can Say; w. Arthur Gillespie; Stern 1909 Both of Us; w. Earle C. Anthony; Chicago: Thompson Music I Want Some Old Style Lager, w. R. Lewis, m. with Carl Gray;Chicago: Roger Lewis When You Know That You Love Someone, w. Arthur Gillespie & Harold Ward; Chas C. Adams 1910 My Tribute; W. Fannie M. Worthington; Chicago: Clayton F. Summy Co. Won’t You Come and Spoon with Me Tonight; w. Francis De Witt; Harry Von Tilzer Music Pub. Co. Dearie, Won’t You Snuggle Close to Me; from Jumping Jupiter, w. Francis De Witt; Witmark I Like to Have a Flock of Men around Me; from Jumping Jupiter, w. Francis De Witt; Witmark. Sheet music. 1911 Persian Princess; Witmark Switchback Rag; Witmark The Pearl Maiden; from The Pearl Maiden, w. Earle C. Anthony and Arthur F. Kales; Witmark Sheet music. Cloudland; from The Pearl Maiden, w. Anthony, Kales; Witmark I Am Lonely for You; from The Pearl Maiden, w. Anthony, Kales; Witmark If One Little Girl Loves Me, from The Pearl Maiden, w. Anthony, Kales; Witmark. Sheet music. Coral Isle; from The Pearl Maiden, w. Anthony, Kales; Witmark 1912 That Typical, Topical, Tropical Tune; from The Pearl Maiden, w. Anthony, Kales; Witmark The Pearl Maiden, selection; Witmark Phi Yell Song; w Harry Weese; Chicago: Harry Auracher 1914 Pavlova Waltz; by Henry B. Ackley and Harry Auracher; NY: Max Rabinoff 1915 We Are with You, Woodrow Wilson, w. Dean Halliday; Newspaper Enterprise Assoc. 1916 Gladys; Chicago: Harry Auracher Egyptia; Chicago: Harry Auracher 1918 “All for Democracy,” Act 6 of 12 in B.F. Keith vaudeville 12-act show 1919 I’m Dreaming of the Girls I Left Behind Me Over There, w. & melody by Tom Johnstone, arr. Harry Auracher; East Orange, N.J.: Thomas A. Johnstone. I Can’t Keep My Mind on My Work, w. & melody by Tom Johnstone & Auracher; NY: Thomas Arthur Johnstone and Harry Auracher Be Yourself; w. & melody by Tom Johnstone & Auracher; NY: Tom Johnstone and Harry Auracher. Oh. Kitty; from Love for Sale, w. and m. Tom Johnstone & Auracher; Stern Spanish Jazz; from Love for Sale, w. and m. Tom Johnstone & Auracher; Stern My Shantung Flower; from Love for Sale, w. and m. Tom Johnstone & Auracher; Stern The Greatest Lover: from Love for Sale, w. and m. Tom Johnstone & Auracher; Stern Give Me a Thrill; from Love for Sale, w. and m. Tom Johnstone & Auracher;Stern. The Dimple on the Knee; from Love for Sale, w. and m. by Tom Johnstone & Auracher; Stern Ask Me Why; from Love for Sale, w. and m. Tom Johnstone & Auracher; Stern Wall Street Blues; from Love for Sale, w. and m. by Tom Johnstone & Auracher; Stern 1920 Jazz Up Jasper; from The Frivolities of1920. w. Tom Johnstone; Remick Be Yourself; from Afgar, w. Tom Johnstone; Feist 1921 Julie; Julie-oo-li-oo; from Afgar, w. Leo Wood and Irving Bibo; Feist Oh Jo; w. Leo Wood; Feist Y-O-U; w. Howard Johnson; Feist I’m Gonna Quit—Saturday; w. P.D. Cook; Feist Sleepy Head; w P. D. Cook; Feist You Know What to Do; w. & melody by P. D. Cook, Archer, & Lew Sandford; arr. Archer; Feist I Can’t Forget; w. P. D. Cook; Feist Cuddle; from Peek-a-Boo, w. P. D. Cook; Feist Hitch Your Wagon to a Star; from Peek-a-Boo, w. P. D. Cook; Feist My Melody Dream Girl; from Peek-a-Boo. w. P. D. Cook; Feist Ornamental Oriental Land; from Peek-a-Boo; Feist 1922 May and December; w. Harlan Thompson; Brooklyn; Harlan Thompson Tyrol; w.& m. P.D. Cook, Al Bernard, Archer; Shapiro, Bernstein Bonnie; from Paradise Alley, words by Howard Johnson; Feist Come Down to Argentine; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist I’m Only Human, That’s All; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist If We Could Live on Promises; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist Happiness; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist In This Automatical World; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist When I Made the Grade with O’Grady; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist Your Way Or My Way; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist Any Old Alley Is Paradise Alley; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson, m. Archer & Carle Carlton; Feist. Sheet music. What You Could Be If You Had Me, w. Howard Johnson; Feist Those Beautiful Chimes; w. Howard Johnson; Feist Eyes of Brown, or Grey, Or Blue; w. Leo Wood, melody Irving Bibo and Archer; Feist Fiddler Paul; w. & m. Howard Johnson & Archer; arr. Howard Johnson; Feist 1923 I’ll Keep on Dreaming, Until My Dreams All ComeTrue; w. Leo Wood, m. Earnest Cutting & Archer, arr. Archer; Feist One Week ago; w. & m. Hayden Shepard & Archer; Feist Come on Let’s Step, Step around; from Little Jessie James, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. I Love you; from Little Jessie James, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. Little Jessie James; from Little Jessie James, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. Such is Life; from Little Jessie James, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist My Home Town in Kansas; from Little Jessie James, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. Suppose I Had Never Met You, from Little Jessie James, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. No Means Yes; w. Harlan Thompson; Feist 1924 The Bluebird; from Little Jessie James, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. Little Jessie James; selection; Feist Chimes; from Paradise Alley, w. Howard Johnson; Feist As Long as Happiness Is There, w. Howard Johnson; Feist If We Could Live on Promises; w. Howard Johnson; Feist What the Future Hold for Me; w. Harry Archer, m. Howard Johnson; Feist When I Made the Grade with O’Grady; w. Howard Johnson; Feist Your Way or My Way; w. Howard Johnson; Feist Desert Isle; from My Girl, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. A Fellow Like Me; When a Fellow Likes a Girlie Like You; from My Girl, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist Rainbow of Jazz; from My Girl, w. HarlanThompson; Feist You and I; from My Girl, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. You Women; from My Girl, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist Before the Dawn; from My Girl, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist A Solo on the Drum; from My Girl, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist I Love you: De Vive La Femme; adaptation francais, from Little Jessie James; H. Varna, F. Rouvray et R.Nazelle; Paris: Publications Francis-Day 1925 My Own; from Merry Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist Pierrot waltz; from Merry-Merry; Feist Poor Pierrot; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist We Were a Wow!; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist The Spanish Mick; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist What a Life; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist You’re the One; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist Little Girl; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist It Must Be Love; from Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. Comedy Song; from Merry-Merry; Feist Ev’ry Little Note; from Merry Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist I Was Blue; from Marry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist 1926 Step, Step, Sisters; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thomson; Feist We Were a Wow!; from Merry-Merry, w. Harlan Thompson; Feist I’d Rather Be the Girl in Your Arms; w. Harlan Thompson; Feist Linger Longer Lane; w. Tom Ford; Feist When I’m with You I’m Lonesome; w. Bugs Baer [pseudo Arthur Baer] & L. Wolfe Gilbert; Feist Pepita; w. Harlan Thompson; Feist. Sheet music. Find a Girl; from Twinkle-Twinkle, w. Harlan Thompson; Harms Twinkle-Twinkle; from Twinkle-Twinkle, w. Harlan Thompson; Harms You’re the One; from Twinkle-Twinkle, w. Harlan Thompson; Harms You Know I Know; from Twinkle-Twinkle, w. Harlan Thompson; Harms Get a Load of This; from Twinkle-Twinkle, w. Harlan Thompson, Harms. Sheet music. Sweeter Than You. from Twinkle-Twinkle; w, Harlan Thompson; Harms. Sheet music. She’ll Never Find a Fellow Like Me;,w. Walter O’Keefe; Feist 1927 I’m Gonna Dance Wit de Guy Wot Brung Me, w. Walter O’Keefe; Feist. Sheet music. Down in Waikiki, w. Dolly Morse; Feist 1928 Maybe It’s All for the Best, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson Now I’m Lookin’ for a Girl, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson Dog-gone; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson I’m Ninety-Eight Pounds of Sweetness; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson Madison Square; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson I’ve Got a Cookie Jar But No Cookies; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson. Sheet music Just a Minute; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson We’ll Just Be Two Commuters; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson. Sheet music Anything Your Heart Desires; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson. Sheet music The Break-Me-Down; from Just a Minute, w Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson. Sheet music Pretty, Petite and Sweet; from Just a Minute, w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson You’ll Kill ‘em; from Just a Minute; w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson. Sheet music. Heigh-ho Cheerio; from Just a Minute; w. Walter O’Keefe; DeSylva, Brown & Henderson 1929 In Sunny Hawaii; w. Eddie Palmer; San Francisco: Villa Moret All I need is Someone Like You, w. Chas. Tobias; Shapiro, Bernstein Adios, w. Irving Caesar; Feist 1930 Alone with My Dreams, w. Gus Kahn; Feist Where the Golden Daffodils Grow, w. Gus Kahn; Feist So Sympathetic, w. Gus Kahn; Feist Lonely for You, My Sweet One, w. Johnny Gruelle; Harms You’re the Sweetest Girl This Side of Heaven, w. Gus Kahn, m. Carmen Lombardo & Harry Archer; Feist. Click for sheet music My One Big Moment, w. Gus Kahn; Feist You Looked so lovely in Your Window, I Fell in Love, w. & m. Harry Archer, Donald Heywood, & Harry DeCosta, unpub; Feist 1931 Love is a Master of Magic, w. Harold Stone [pseud. of E. Vonder Goltz], m. Walter Lounsbury [pseud. of Harry Archer; Carl Fischer 1933 Talking in My Sleep, w. John Mercer, m. Harry Archer & Margo Millham; Miller Music The Love Moratorium; or, You Can’t Take It, w. Will Johnstone; East Orange, NJ: Will Johnstone 1934 Am I Delighted; from Lucky Break, w. Harlan Thompson & Douglas Furber; Feist I’d Like to Know; from Lucky Break, w. Douglas Furber; Feist Tum-Tum-Tum; from Lucky Break, w. Harlan Thompson & Douglas Furber; Feist You Can’t Take It; from Lucky Break, w. Will B. Johnstone; Feist A Kick in the Pants; from Lucky Break, w. Walter O’Keefe; Feist 1935 Rainbow, w. Haven Gillespie; Feist 1939 One Night in Bombay, w. Mack Davis, m. Joe Rines & Harry Archer; Shapiro,Bernstein World’s Fair Waltz, w. & m. Nick Kenny, Charles Kenny & Harry Archer; Feist White Sails (Beneath a Yellow Moon), w. & m. Nick Kenny, Charles Kenny & Harry Archer; Feist I’ll Be Waiting Around, w Brick Holton; unpub. NY: Irving Berlin 1942 We Were Lucky Together, w. Gladys Shelley; Mills Music 1943 I’ll Be Hangin’ around, w. Harlan Thompson & Harry Archer; unp., NY: Harry Archer Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed