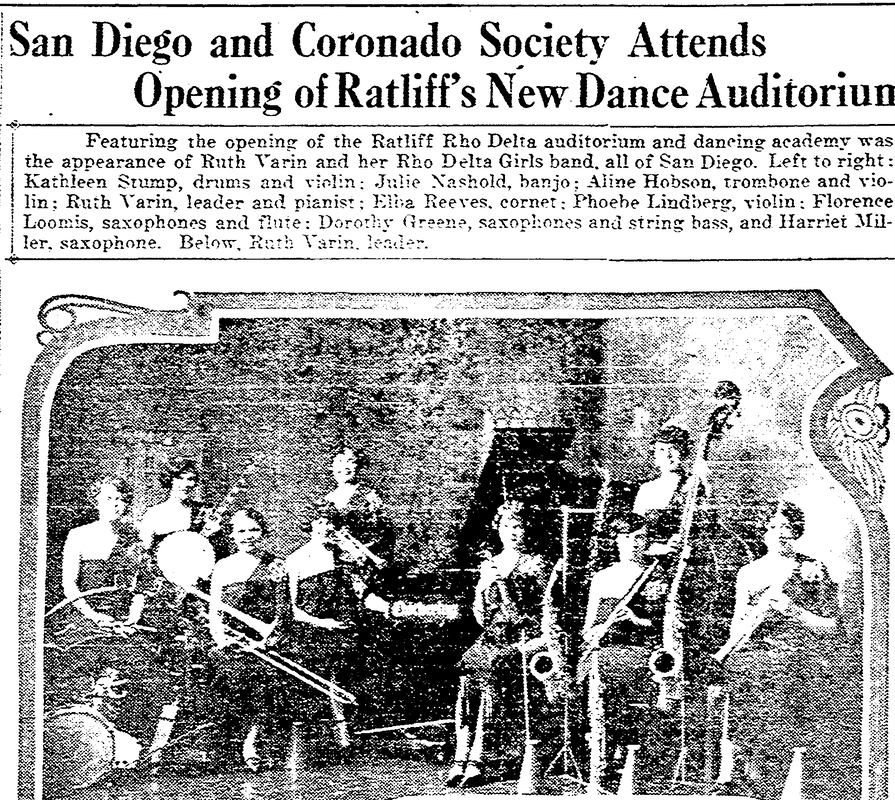

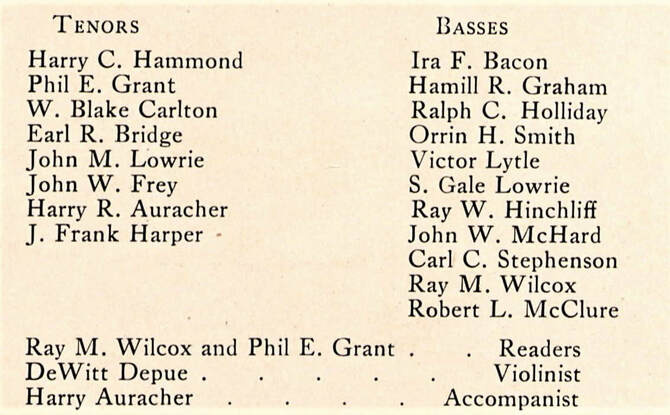

Background and Education Largely forgotten, composer and orchestra leader Harry Runkle Auracher was born in Creston, Iowa, on February 21, 1886, to George Auracher, a plumber, and Mary F. Runkle Auracher. Harry's sister Ruth, born just under two years after Harry and also a professional musician, later told a reporter, “My mother was a fine pianist, and she taught my brother and me the foundation of music, the rest I have learned in the world of experience. I started playing for shows at the theatre in my home town when I was a little girl.” Young Harry seems to have led a similar life because he was nicknamed “the boy pianist.” The November 6, 1914 issue of the Baltimore Evening Sun states that Auracher wrote his first march at 14. As a youth, Harry also traveled and performed locally in Agnew’s Juvenile Band, directed by Frank E. Agnew, who owned a Creston clothing store. Harry Auracher attended Michigan Military Academy where, according to the Greater West Bloomfield Historical Society, he played tuba in the band. Other sources, including David Jasen, say he played trombone. Michigan Military Academy, Orchard Lake, Michigan, Twenty-eighth Year, September, 1904 lists Auracher among the 1903 graduates. After leaving Michigan Military Academy, Auracher attended Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois, where he joined Phi Delta Theta fraternity and, according to a 1925 Saratoga, New York newspaper, “thumped pianos at fraternity house parties.” The 1907 yearbook--the year of his graduation--reveals that he sang in the Men's Glee Club and served as accompanist. Multiple newspaper sources indicate that Auracher caught the attention of Princeton University, said to have recognized his potential for contributing to its music productions. The Catalogue of Princeton University, 1906-1907 lists H. R. Auracher as a “Student Qualifying for Regular Standing,” which may indicate the university had admitted him based on his talent rather than standard academic qualifications. In April 1907, Pittsburgh's Daily Post credits Harry Auracher and six other Princeton Triangle Club members with writing The Mummy Monarch, an original show then on tour in Pittsburgh. “The performance of The Mummy Monarch demonstrated that while the boys may be getting an education in the classics, they are managing to keep pace with the moderns," the paper declared; “There are men who are responsible for some of the late comic operas given us by the professionals who might go learn of these Princeton undergraduates how to do the thing well. For both the book and music of The Mummy Monarch were composed by the students who presented it, and the opera has more go and fun in it than many a work that has been palmed off on the public as ‘the hit of the season.’” In the Directory of Living Alumni of Princeton University, 1917, Auracher’s name appears second in an alphabetical list of 1910 graduates, but the volume provides neither an abbreviation to indicate his major, nor a current address, both of which are included for the majority of alumni. Auracher's Music Career: The Beginnings, 1908-1912

After leaving Princeton, Auracher moved to Chicago. The New York Times later described his move: Then, armed with a diploma, a railroad ticket and $30, he charged upon Chicago, determined to earn his living as a stock broker or a bond salesman, or something else equally nice and refined. It was not considered quite respectable in those days for a young man of good family to feed and house himself by means of a piano. Shortly after his arrival, Archer also taught music. In addition to teaching, Auracher organized a sizable orchestra. The group regularly appeared at Northwestern University social events in nearby Evanston. Approximately three weeks before the February 17, 1911 formal dance, the Daily Northwestern announced: From all appearances a large number will turn out, but not enough to make the floor crowded. Harry Auracher will furnish music for the occasion with a twenty-piece orchestra. This is a sufficient guarantee that the music will be all that could be desired.

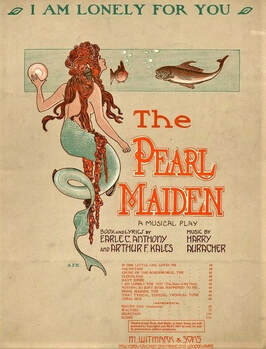

By the 1912 Chicago directory entry, Auracher apparently had begun to regard himself as a professional musician, not just as a music teacher. The Pearl Maiden, Auracher's First Musical Comedy Score With a company of 75, including stars Jefferson De Angelis, Flora Zabelle, and Elsa Ryan, The Pearl Maiden perhaps attracted the most attention for its dancing girls. Reviews were mixed, some humorous in their witty condemnation: There are a number of musical selections, some so so and some not so much so. Then there are three acts, the first the best, the second hardly more than a sketch, and the third act a patience tester. Bedecked in gems but without brilliancy was “The Pearl Maiden,” who made her initial bow to Broadway last night in the New York Theatre. In the discovery of her habitat, the South sea Islands, her three sponsors showed originality, but they seemingly were content to take their credit on that point alone because neither the book nor the music is of a kind that will leave an enduring impression. The lines that carry the Pearl Maiden through a series of vicissitudes are as trite and humorous as an almanac, reflecting sadly on the imagination of Earle C. Anthony and Arthur F. Kales. Neither of those men has been heard on Broadway before, but they will return into obscurity accompanied by Harry Auracher, who permitted the music embellishment to go under his name. . . . Some reviewers were a bit kinder:

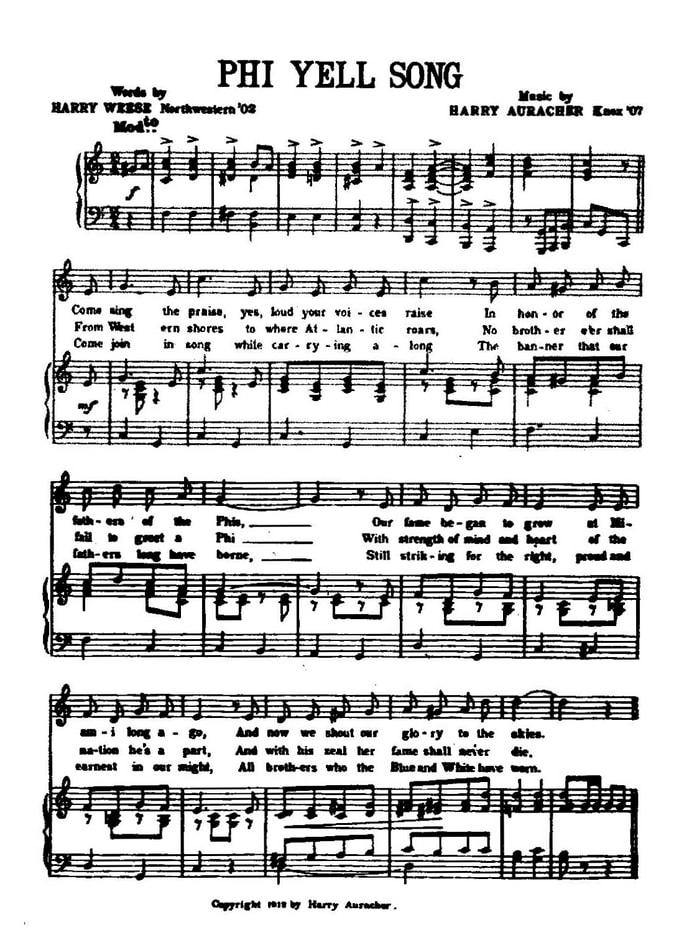

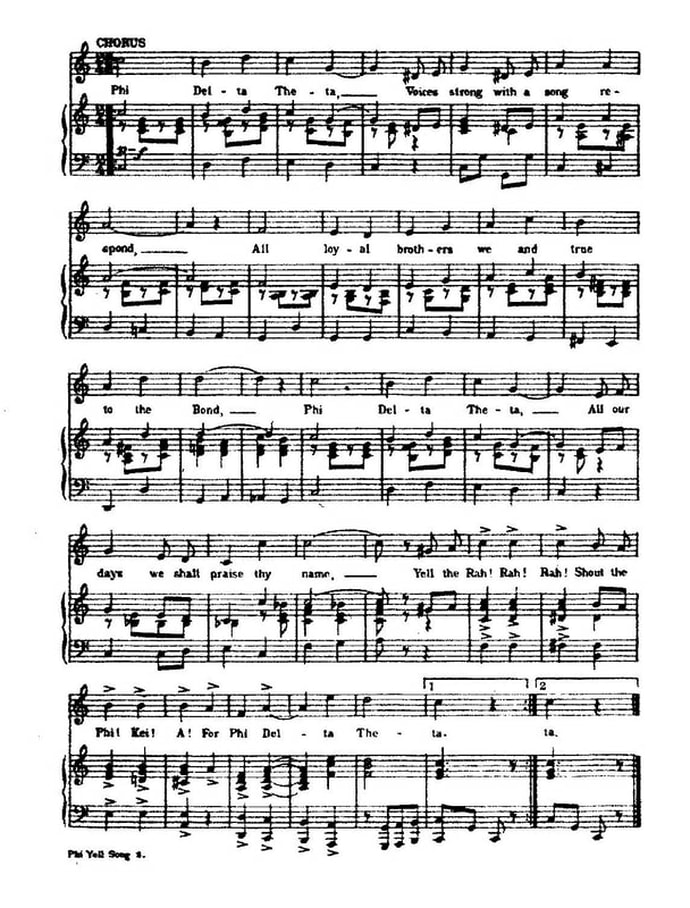

The Pearl Maiden was composed by a Mr. Harry Auracher. Mr. Harry Auracher must, during his perchance boyish life, have sat and enjoyed many operas. He must have eaten and digested them thoroughly. Some of them reappeared in The Pearl Maiden. A Mr. Harry Auracher appeared to have been awfully fond of Puccini and Sir Arthur Sullivan. They are nice to be sure. In his overture, a Mr. Harry Auracher really Puccini’d us on the belief that we were going to get a sort of mince-meat of Boheme and Butterfly. It was quite wondrous and daring. Later, our dear old friend Pinafore bobbed up serenely in a quartette. Pinafore is really charming and not a bit out of date. We could have stood a lot more of it in The Pearl Maiden, also The Mikado, The Gondolier and The Pirates of Penzance. Following comments on other people contributing to the show, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle continued: Among these, some credit is due to Mr. Auracher for three or four tuneful airs, and rather more to Mr. German for the introduction of dances in which a remarkably lively pony ballet combines acrobatic excellence with the display of as much lingerie and hosiery as any baldheaded pa has the right to expect. The Phi Yell Song At the end of 1912 into early 1913, Auracher attended the Phi Delta Theta annual conference held in Chicago and impressed his old Knox College fraternity brothers, as well as brothers from other colleges, with his Phi Yell Song, written in collaboration with its lyricist and fraternity brother Harry Weese. First performed on New Year’s Eve at the convention’s Smoker and again with Auracher's fifteen piece orchestra at the January 2 dance, the Phi Yell Song remained popular with Phi Delta Theta chapters for at least several years much as predicted in The Scroll of Phi Delta Theta, Volume XXXVII, 1912-13: This is one of the best Phi Delta Theta songs ever written and the music is irresistible. Everybody was delighted with the words and air and they were sung many times during the convention. It will hereafter be a favorite at chapter meetings, alumni reunions and province and national conventions, and it will be a valuable addition to the next edition of the fraternity song book. On other pages, The Scroll also remarked: And the music! Why, it seemed that every Phi was chuck full of music. Brother Harry R. Auracher launched his new Phi Yell Song—and it is a corker—the lyrics full of Phi spirit, and the tune catchy as a popular song hit, with a gridiron tempo. The music, under the direction of Auracher, was just the right sort to stir up everybody, and the Phi Yell Song, for which he wrote the music and Weese the words, caught everybody’s fancy. Its lilting tune is still ringing in the ears of everybody who heard it that night. Auracher registered the copyright in his name. Engagement and Marriage

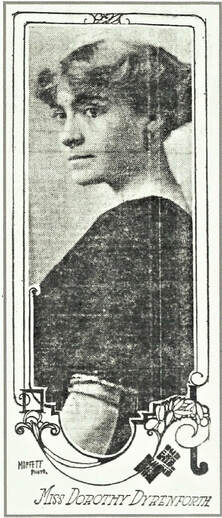

I’m taking up stage work because I believe I have a greater talent for it than for anything else. I have received a good education, and I believe every young woman should have some aim in life and some work to do. Never for a moment have I ever thought of being idle. The niece of playwright Douglas Dyrenforth and cousin of singer Robert C. Dyrenforth, she soon appeared at the Cort Theater as Helen, the sister, in An Everyday Man, starring Thomas W. Ross. Miss Dyrenforth's acting career must have been short-lived because nothing has been found to document further performances. However, it's easy to see how Harry Auracher and this accomplished young woman with her musical and dramatic family history might feel a mutual attraction and how her wealthy, educated socialite family might accept an aspiring young orchestra leader and composer, who had studied at Princeton. One of the society weddings of 1913 took place on April 16 at Grace Episcopal Church in Oak Park, Illinois. Auracher was 27 and Dyrenforth 23. Tango Teas

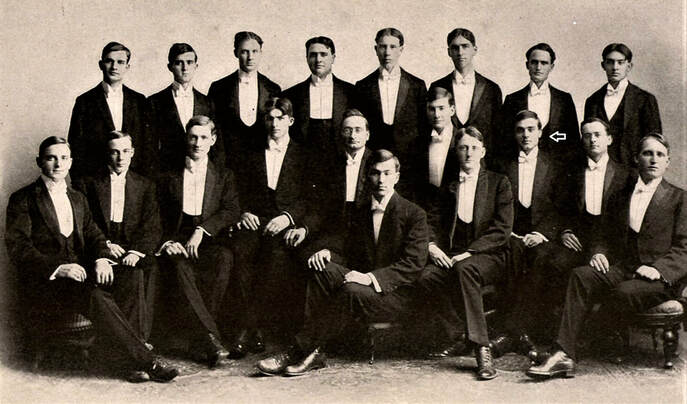

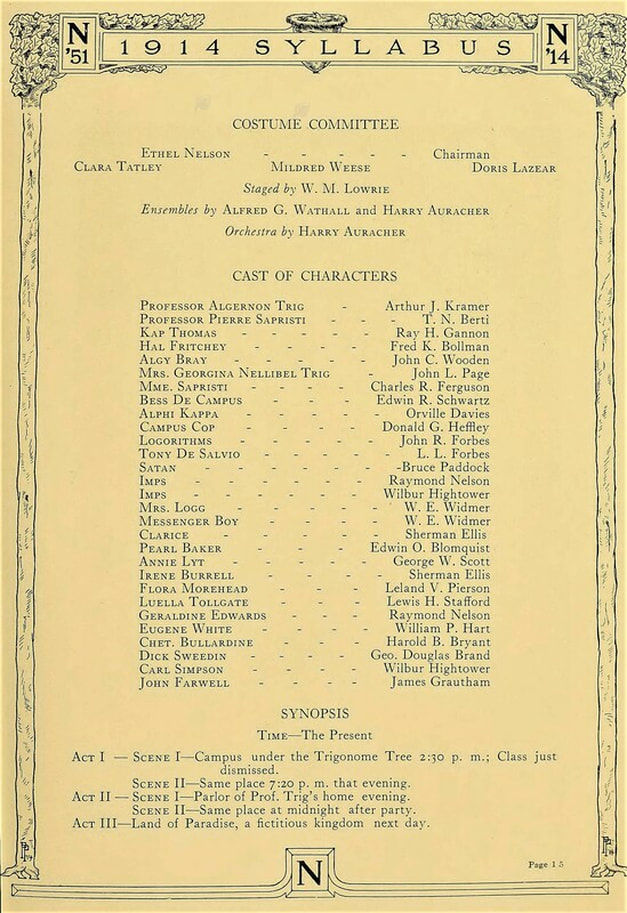

Did Harry Auracher’s orchestra play for Dorothy’s dance-teas? Newspapers don't say, but we will later see that he did perform for at least one such event. Harry Auracher's Continuing Career, 1914-1917 Under the Trigonome Tree Regularly playing for Northwestern University dances, Auracher's Orchestra also performed for a Northwestern student play, Under the Trigonome Tree. Although this performance was of little significance, the 1914 Syllabus, Northwestern's yearbook, does more than document his participation. It includes Auracher's photo, front row left. By 1914, Auracher viewed his orchestra as a major part of his career and included a second entry in the Chicago directory for Auracher's Orchestra. Auracher was now musician and director. A Prize-Winning Waltz

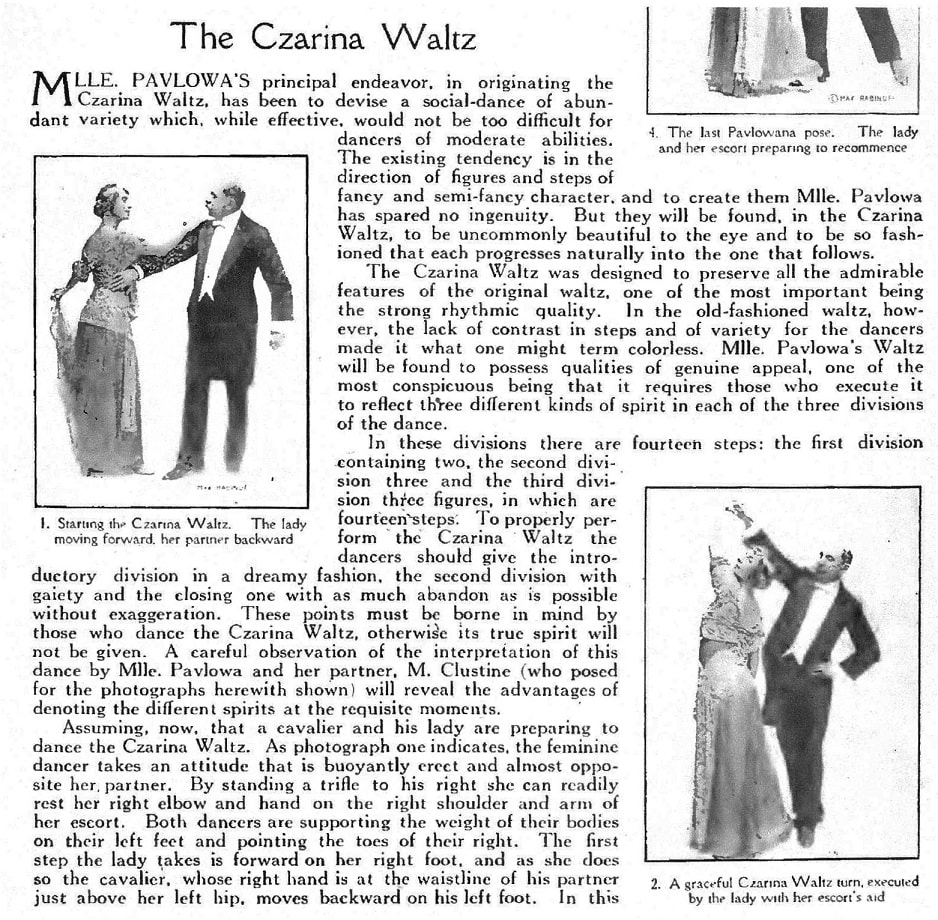

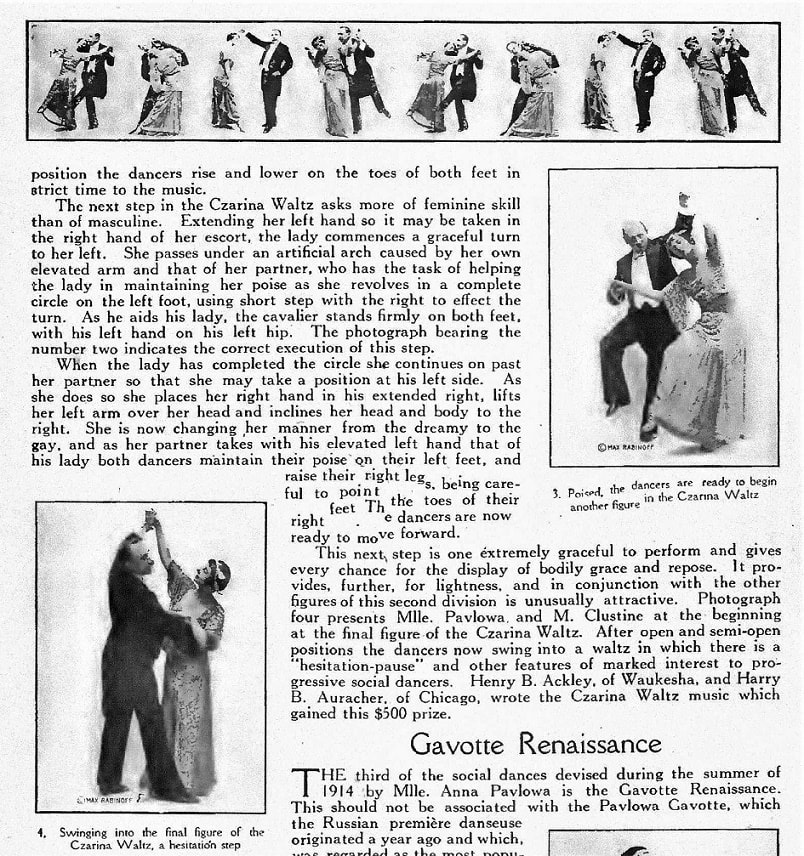

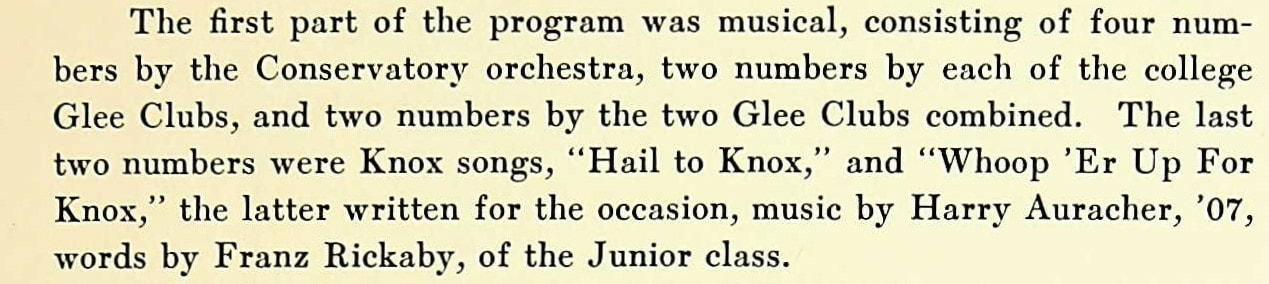

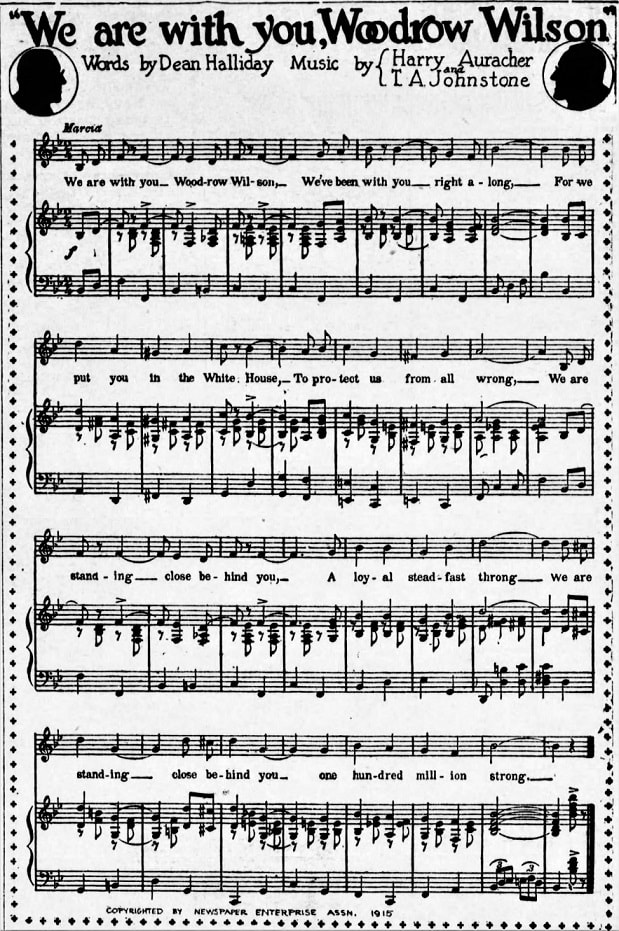

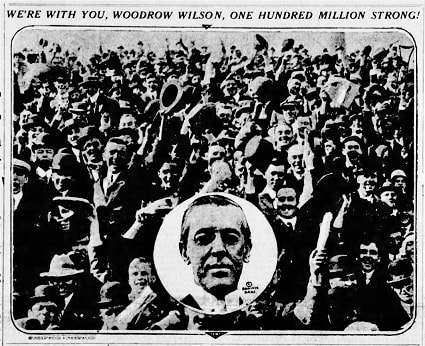

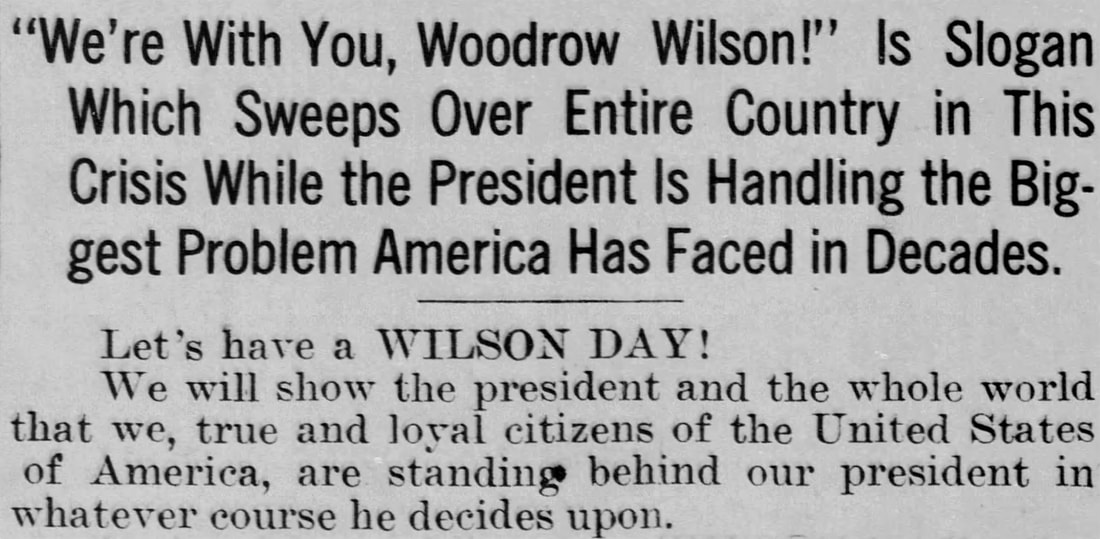

Prior to her 1915 performance in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the Grand Rapids Press explained: The victorious candidates for the $1500 in prizes offered at the beginning of last summer did not find their pathway to success unchallenged. There were, in point of fact, three hundred and thirteen other compositions against which their own were arrayed, the total number of individuals sending piano scores to the judge, numbering 288. Pavlowa was to perform a hundred times in the U.S. and Canada during 1914-1915 season, and original music had been sought for part of her performance, which she called “The Dance of Today.” Auracher and collaborator Henry B. Ackley divided the waltz category prize for a piece sometimes called the Czarina Waltz and sometimes Pavlowa Waltz. Pavlova was said to have chosen the winners, but impresario Max Rabinoff, who introduced Pavlova to the U.S. and had overseen the contest, copyrighted Ackley and Auracher’s tune along with the winners of the two other dance categories. The following discussion of Pavlova’s dance performance appeared in Max Rabinoff’s Mlle. Anna Pavlowa, a booklet prepared for her 1914-1915 tour. Little is known of H. B. Ackley although newspapers and public records provide a basic picture. The son of a physician, Henry Breck Ackley, born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, was a 19-year-old music student at Carroll College, Waukesha, when he shared the prize with Auracher. How the two came to collaborate is anyone’s guess, but when announcing the winners, the Baltimore Sun commented that Ackley had “gained for himself a piano teacher’s diploma when he was barely 17 years old, at which age he was playing in public with orchestra and receiving critical commendation in print.” With slightly over a hundred miles between Chicago and Waukesha and orchestras in common, it’s conceivable that the Ackley and Auracher may have met through shared music interests or possibly even that young Ackley was interested in entering the contest and contacted Auracher. Whatever the case, Ackley appears to have had talent and training. He studied with Oshkosh pianist/organist Clarence E. Shephard, who had studied with Marcel Dupré and Alexandre Guilmant in Paris. According to the Musical Courier, Shepard “enraptured the audience by his transcendent execution” during a 1908 Paris concert. Learning from Shephard, Ackley was occasionally playing church organ by 1915. Ackley would later complete his music degree at Carroll College and earn a master’s degree at the University of Chicago. By the 1920 census, he was teaching in DeKalb, Illinois. By 1930, he was teaching in New York City where he spent time at Allen-Stevenson private day school, Collegiate School, and Columbia Grammar School. In January 1943, he left Columbia for Englewood Boys School, New Jersey, where he taught French and Spanish. Whether or not he also taught music at any of these schools, he may have continued teaching private lessons and seems to have found other ways to use his skill. Before the end of his first semester at Englewood, he composed the music for a show put on by the boys school and Dwight School girls. Another Knox College Song As evidenced by Auracher’s setting to music a lyric written by a current student, Knox College apparently continued calling on Auracher when needing another school song. This time the occasion was Founders Day, February 15, 1915. Santa Fe Reading Room Gigs According to the January 15, 1915 issue of Special Libraries, a journal, the Santa Fe Railroad supported twenty-four Reading Rooms for employees along its routes, providing a library in all, as well as sleeping rooms and entertainment, such as billiards, in half. For four months each year, the Santa Fe offered cultural programs, consisting mainly of concerts, but occasionally of speakers. A small number of articles appear in period newspapers to document Auracher’s participation: That orchestra program Mr. Busser sent us on the Santa Fe Reading Room course, Tuesday night, is one of the finest things he has ever sent us. The Auracher Orchestra of Chicago (six people) is scheduled for the next Santa Fe Reading Room course. This will be given on Monday, March 8. The company will arrive on no. 21. The entertainment will be given at the Sultana theatre, as usual. This company is highly recommended and should prove one of the best on this year’s course. (Williams [AZ] News, Mar. 4, 1915) The Santa Fe bureau of entertainments is looking for something above the average and out of the hum drum, and we believe we have found it in the Aurachers. It is easy to procure musicians in Chicago, but it is not possible to always get the best, but we have them in the Aurachers. I have heard only one snare drum solo in my life and that was given by Mr. Straight of the Aurachers. One connects the snare drum with noise, and expects to hear it in marching columns and in battle, but who ever thought it could be played as most fascinating music? So with the banjo, the guitar, the fiddle, the cello, and even the piano; each of these players will give you a different idea of his instrument. My main trouble is that all the boys on the line will wish to hear them and I can place them at only ten points, but let me ask you to go to them, if they cannot come to you (Dodge City [KS] Daily Globe, March 14, 1916) The same article indicates current instrumentation and orchestra members: Harry Auracher, piano and manager; Louis Lipstein, violin; Eugene Adams, tenor and banjo; Oswald G. Stark, cello; Frank Lannom, harp and guitar; Edward B. Straight, drums. The last readily available Chicago directory online (1915) again shows an increased focus on the orchestra, with Auracher now identifying himself solely as director, no longer musician and director. Nevertheless, Auracher’s composing career was just getting off the ground, with his major theater work not to come until the 1920s. We Are with You, Woodrow Wilson: A Song Drawn from History On Tuesday, June 15, 1915, the Evansville [In] Press published a song by Dean Halliday, Harry Auracher, and T. A. Johnstone. On Wednesday the 16th, the Tacoma [WA] Times published a persuasive appeal to the residents of Tacoma for a Wilson Day—a day to “shout the President's name from the housetops,” and “to break down party lines and thank God we’ve got such a man on the job in Washington!” Focusing on its call for unified patriotic fervor in support of Wilson, the Times failed to mention the music appearing immediately below the appeal—the same song that had appeared the previous day in Evansville. On Thursday, the Tacoma Times declared the song a hit and filled in some missing information before Wilson Day, which had been hurriedly scheduled for Saturday, Have you tried the new song written in honor of President Wilson entitled We Are with You, Woodrow Wilson? Also on the 17th, a day after the Tacoma Times had published the song, the Seattle Star printed it, instructing everyone to learn it and announcing it would “be sung for the first time in public at the Grand theatre at noon Wilson day.” In Seattle, that meant Tuesday, June 22, three days after Tacoma’s Wilson Day.

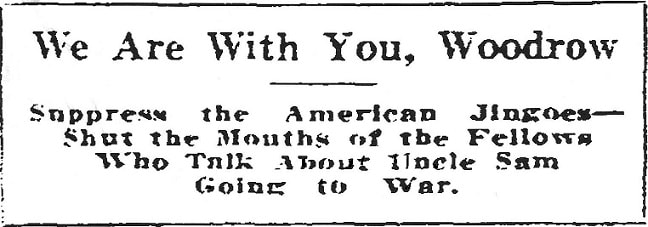

The song soon spread to Los Angeles and San Francisco where it played a role in California Wilson Day celebrations. Although newspapers across the country are not filled with this Auracher collaboration, we might infer that the song achieved and retained considerable popularity because nearly nine months later, variations appeared in the Salt Lake Telegram and Duluth’s The Labor World, opening with these lines: We’re with you , Woodrow Wilson, We are with you, Woodrow Wilson, As logical as this assumption might seem, anyone making it could also be entirely wrong-headed. A look at events preceding the song reveals that lyricist Halliday probably drew the song title from newspapers more than a year before his lyric and Auracher and Johnstone's music appeared. Shortly before Wilson's inauguration on March 4, 1913, Mexico's President Madero and Vice President Suarez were toppled from power and shot in the middle of the night as they were driven to prison. General Huerta, one of the men behind the coup, seized power. Various others, including Villa and Zapata sought control. Once in office, President Wilson refused to recognize any Mexican government and eventually ordered Huerta to step down. Recalling then candidate Wilson's 1912 "Win with Wilson" campaign slogan, the Rock Island [IL] Argus added, "We are with you yet, you bet, Woodrow Wilson." Not Halliday's exact words, but close. The idea would persist and the words become closer. Despite talking tough and sending some troops to the border near El Paso, Wilson did not want to go to war. To celebrate Wilson's first anniversary in office, many newspapers declared their support. With a reputation of original verse, St Louis Post-Dispatch Clark McAdams, penned a poem published March 6,1914: We like you, Woodrow Wilson, Over the next three weeks, other papers, such as the Boston Globe, the Buffalo Enquirer, and the Anaconda [MT] Standard reprinted McAdams' poem. As fighting escalated in Mexico, a small fleet of American ships reached the oil-rich port of Tampico to protect and rescue Americans living there. When Huerta's men arrested several marines and officers, the American Admiral in charge demanded an apology and the firing of a military salute to the American flag onboard the men's ship in the harbor. Although the men hd been released, Huerta refused the military salute. Emotions ran high onboard ship and back in the States. Wilson agreed that Huerta's troops had insulted the U.S. and should salute the American ship. Time had come for action. On April 20, 1914, the Washington Times declared, "All eyes, and the interest of the nation, were centered upon the Capitol, under whose dome at 3 o'clock this afternoon the President of the United States, in person, is to ask Congress to uphold his iron hand in dealing with Mexico." Expecting harsh measures and possibly a declaration of war, the House and Senate planned for the afternoon session by passing a resolution. According to the Times, the resolution assured the President, "in parliamentary language, that: "We are with you, Woodrow Wilson." On May 16, 1914, after Wilson had dispatched enough ships to control every port on Mexico's east coast, Martin Dies, a Congressman from Texas, remarked, "We have gone down to Mexico to serve mankind if we can find out the way. We do not want to fight the Mexicans. . . . A war of aggression is not a war in which it is a proud thing to die, but a war of service is a thing in which it is a proud thing to die." The Waco Times-Herald reporter who had quoted Dies, followed up with his own opinion: For the life of us, we don't know where the President gets the Constitutional authority to go into a foreign country to serve the distracted inhabitants. We can understand how he might stretch his authority somewhat for the protection of the lives and the property of American citizens, be hanged if we can make out either the necessity or the propriety of a war with altruistic aims. Since this expression of unity with President Wilson had appeared in newspapers across the country for a year before newspapers published Halliday, Johnstone, and Auracher's song, we can infer that Mexico's civil strife and Wilson's tough talk but refusal to go to war inspired the song title and Halliday's lyric. Later newspapers support this conclusion. On June 30, 1915, as Evansville, Indiana planned its own Wilson Day, the Evansville Progress helps clinch the connection between the song title and the ongoing crisis in Mexico: On August 22, the Detroit Times sided with Wilson's decision to maintain U.S. neutrality and spoke out against extreme nationalism. With the history behind the song identified, who were Auracher's collaborators, Dean Halliday and T. A. Johnstone? Although both men later changed careers, they were Chicago journalists in 1915. By no means was either a full-time musician although Johnstone and Auracher would collaborate on a few later theater projects. Born in Evanston, Illinois, Thomas Arthur Johnstone (1888-1970) graduated from Chicago Art Institute and worked in Chicago as a newspaper artist/cartoonist. Sometime in 1915 or 1916, he left Chicago for Cleveland, Ohio, where he served as art manager/editor of Newspaper Enterprise Association, possibly indicating that Johnstone was responsible for Newspaper Enterprise Association’s copyright on the song. After working as an editor/manager for the New York World’s Press Publishing Company and losing the job when the paper was sold, he founded Thomas A. Johnstone Comic-Art Studios and began soliciting cartoon work from advertising agencies, whose clients wanted cartoons or cartoon characters in their next marketing campaign. Over time, Johnstone took on a partner and the firm became the iconic Johnstone and Cushing. Although he remained interested in Broadway theater and occasionally played a role in launching a new show, including helping the Marx Brothers on their road to success, Tom Johnstone’s main career contribution was to the cartoon advertising field. Click here if interested in learning more about Johnstone's cartoon advertising career. Born in in Toronto to an English father and Canadian mother, Joseph Dean Halliday (1889-1960) came to the U.S. as a toddler with his parents. In 1912, he began a stint as a foreign correspondent in Tokyo and at the time of We Are with You, Woodrow Wilson’s appearance in 1915 newspapers, Halliday was reporting for Chicago’s Day Book, writing under his middle (mother's maiden) name and his last name. Halliday's World War I draft registration, completed in Brooklyn, NY, lists him as a Chicago Herald “newspaper man.” Soon after, when Canadian-born Halliday became an American citizen, he was living in Cleveland, the same city as Johnstone. Halliday served on the Western Front during part of 1918 and 1919 and appears to have had a short stay at Walter Reed Hospital before being honorably discharged in late March 1919. Following discharge, he went to work for the Anti-Tuberculosis League in Cleveland where he remained for many years, continuing to travel and to write in support of the cause. Although the power struggle continued in Mexico and raids across the southern border led Wilson to amass National Guard troops on the U.S. side of the border in 1916, the timely 1915 song was just a song that had its day. Over the next couple of years, Auracher focused on his orchestra, not on composing. However, his career path and Tom Johnstone's would cross again. Miscellaneous Chicago-Area Performances, 1916-1917 As a Princeton alumnus, Auracher must have enjoyed playing for the Princeton Club of Chicago’s 1916 Midwinter Beefsteak Dinner. The Princeton Alumni Weekly reported that Auracher's Orchestra “was one of the most enjoyable features of the evening.” If Auracher had not performed for his wife’s earlier tango teas, he did perform at her March 1916 dance event: Mrs. Harry Auracher, formerly Miss Dorothy Dyrenforth of Evanston and a member of the alumnae chapter of Delta Gamma, will give a Spanish dance this evening at the entertainment, Tableaux Vivants, to be given at the Evanston Women’s Club. Mrs. Auracher will be accompanied by music composed for the occasion by Mr. Auracher.

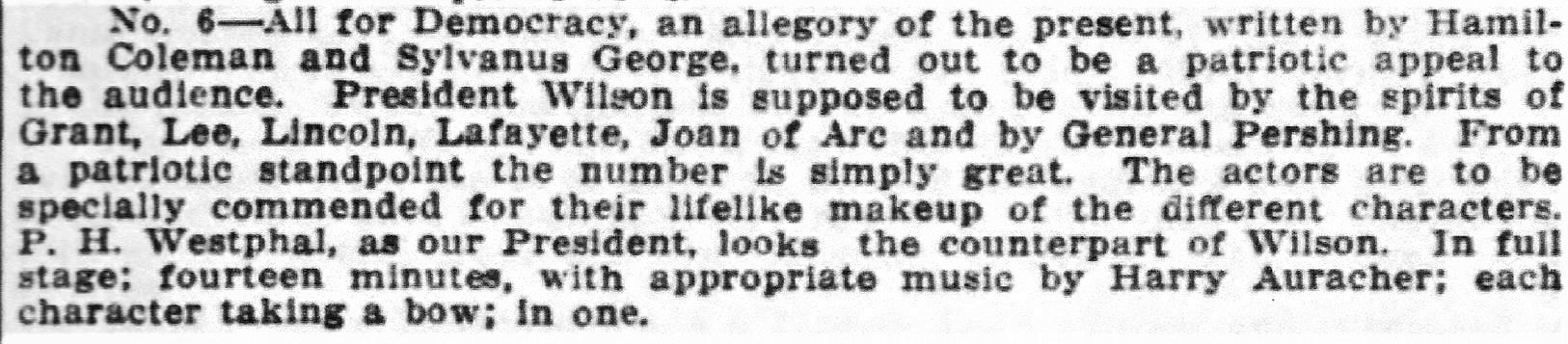

Auracher’s Orchestra, sometimes with Auracher at the piano and sometimes not, continued playing for Northwestern University dances, including proms. Several of the local Daily Northwestern comments shed light not only on the orchestra’s music, but also on its shrinking size as the country doubled its Army in preparation for war and eventually declared war against Germany on April 6,1917. If the happy spirit of the dancers was any gauge, the Senior Promenade at the gymnasium last night was a decided success. From the moment that the first strains of “Dancing Around” came from Harry Auracher’s orchestra until the wee hours of the morning when the dance closed at 2 o’clock the crowd showed every sign of enjoying itself immensely. (May 2, 1914) The same high class popular music is guaranteed by the Harry Auracher orchestra, with Mr. Auracher himself performing on the piano. . . . The music was of the usual Harry Auracher type, and the program was particularly characterized by a large number of the latest song hits. (April 6, 1915; April 10, 1915) Harry Auracher will furnish the music with a twelve-piece orchestra. There will be twenty-four dances on the program, including three extras. The grand promenade will start at 8:30, giving plenty of time for all of the twenty-four dances. (March 17, 1916) On account of war conditions, it is generally felt that the usual elaborateness of former Proms would be entirely out of place, hence this year the affair is to be much simpler. Tonight’s the night! . . . Harry Auracher’s five piece orchestra, namely, to wit, piano, drums, banjo, saxophone and xylophone, will be in fine trim . . . (April 19, 1918) Having started at twenty musicians in 1911, Auracher’s dance orchestra for Northwestern University events had decreased to twelve in 1916, to eight before the end of 1917, and to five little more than a half year before the armistice. More Forays into Theater, 1918-1919 Although still living in Chicago and maintaining his usual orchestra performances, Auracher increased his musical theater activities. All for Democracy, 1918 With American troops fighting in Europe, his next score was heard on April 15, 1918, in the 6th act of a 12-act vaudeville show at B. F. Keith’s Palace Theatre on Broadway. Decorated with war posters, the Palace’s lobby, according to Billboard, “was a vast Liberty Bond sales station.” Preceded by everything from a Palace Orchestra performance, “high-class drawing room singing numbers,” and Fink’s comic Mules, Act 6 paid tribute to Wilson:

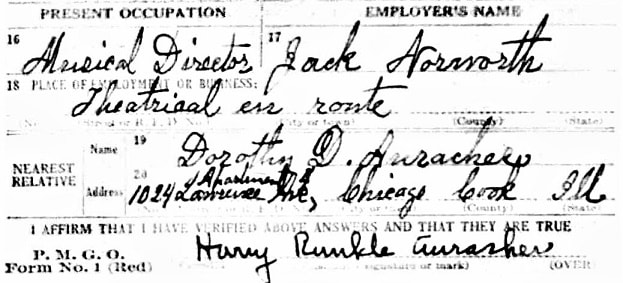

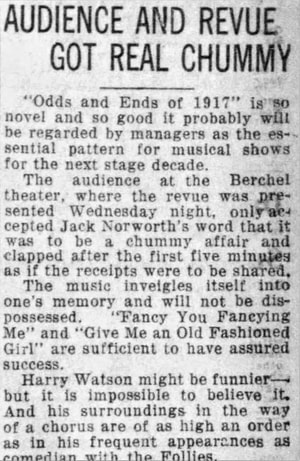

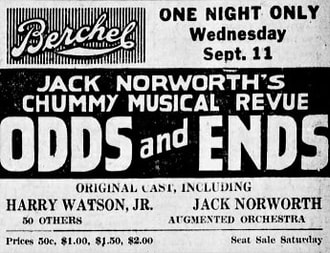

Although Auracher composed the music and Auracher’s Orchestra played it on Broadway, Variety pointed out that the orchestra was directed by Phil Welker. After criticizing the one-act play, Variety concluded, “The one point commendable is the musical arrangement.” Odds and Ends, 1918 Auracher’s undated WWI draft registration, with Fort Madison, Iowa, and Chicago stamps, indicates that he was “en route” with a Jack Norworth show.

When Odds and Ends folded, Archer found himself in New York City Hitchy Koo 1918

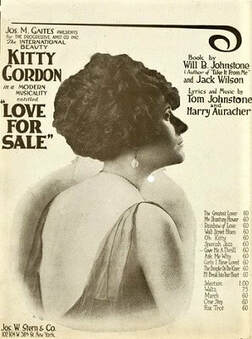

Love for Sale, 1919

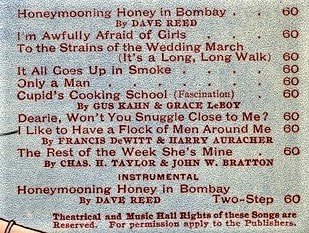

Johnstone and Auracher's Love for Sale show tunes included "Oh, Kitty," "Spanish Jazz," "My Shantung Flower," "The Greatest Lover," "Give Me a Thrill," "The Dimple on My Knee," "Ask Me Why," and "Wall Street Blues," all copyrighted by Jos. W. Stern. Problems plagued the show from the start. Even before its pre-Broadway tour, a New York Times critic dismissed it as exemplary of the increasing number of popular shows written by nobodies: Although that critic's remarks indicate that Love for Sale had been scheduled to run in New York City, it would not become Auracher's first smash Broadway hit. Following an October 9 pre-Broadway performance in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania--the tours second stop, the Times-Leader reported the show's ill-fated start. Not only did it arrive late from Harrisburg due to a poor train connection, the sold-out first evening's performance had to be canceled so that the stage crew could make necessary adjustments. Elaborating on production obstacles, the Times-Leader also provided a reason for the tour that would have displeased the show's creators, but that pleased Wilkes Barre's theater manager: Never in the history of theatredom has there been a production so massive, so elaborate in scenic effects and so stupendous in scope, presented in any local playhouse. This was evident today by a Times-Leader reporter who spent a couple of hours at the Nesbitt watching final settings made for this afternoon's matinee after alterations and specially-constructed additions to the stage were made. Part of this story doesn't ring true--most importantly, because the Shubert brothers built the Shubert Theatre in 1913. It was not a recent aquisition. During the weeks that Love for Sale was on tour, other shows appeared at the Shubert. Of course, the Shuberts probably had booked other shows many months in advance. But then why would Love for Sale have begun rehearsing so long before it could open? Might the plan have been to work in the show if another flopped? Whatever the realstory,theShuberts seem to have been behind the tour. What would normally have been a brief out-of-town trial run before opening on Broadway instead turned into a fall tour through Pennsylvania, Delaware, Indiana, and Michigan. The Wilkes Barre Times-Leader reveals that every effort seems to have been made to succeed. Will and Tom Johnstone accompanied the show, at least at the start, with Harry Auracher also there "to supervise the many musical numbers that enter[ed] into its staging." In small-town Indiana, the show received its most lavish praise. However, that must have been promotional material since it appeared in more than one paper along the route: Love for Sale is said to be a treat for lovers of musical extravaganza for it takes one into the realms of refined comedy where there is real humor without undue exaggeration and amusing studies of character. It is said to be full of enchanting melodies, charming romance, joyous scenes, pretty dances and a gay atmosphere of life. Love for Sale folded after a successful week's run in Detroit but with nowhere to go from there aside from a few one-night stands. One might say that Love for Sale did have its run at the Shubert, for this was a Shubert Organization theater. According to the New York Clipper, the production returned to New York, the troupe disbanded, and Manager Gaites reported that he would hold the show "until some time in the future, when the congestion on the road lightened." That time never came, nor did the show's opening on Broadway. Harry Auracher seemed destined to remain a Chicago-based band leader. Yet he would not. An upcoming blog entry will pick up where this one leaves off and will complete the Harry Auracher story. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed