|

After stumbling across a funny anecdote involving Jean Lenox and Harry O. Sutton's visit to an "Old Ladies Home," I originally intended to share that one item, which sounded like something that could happen where my mom lives. However, one thing led to another. When I decided to see what else I might easily turn up about the song-writing team, I found other anecdotes. A few contradictory newspaper items led me on a quest to determine Lenox's relationship to Sutton. How far should we trust the newspaper anecdotes? To what extent might they have served as good public relations, perhaps to enhance the song-writing team's reputation? Exactly who were Jean Lenox and Harry O. Sutton? What can we learn from newspapers and public records? I'll admit to not finding clear-cut answers to some of my questions but will offer several reasons for the remaining mysteries. Perhaps someone will have the curiosity and time to look for more. Biographical Backgrounds and Mysteries Harry O. Sutton (1881-1911)

During a Presbyterian social at their home in early April, 1893, 11-year-old Harry gave what may have been his first public performance when he and his aunt entertained guests with their unspecified piano duet.

Scott Joplin could not have conceived and composed a more suitable musical and dramatic finale for Treemonisha. Ed Berlin provides an excellent overview of Joplin’s accomplishment: Treemonisha stands on a bench and calls the steps, sometimes assisted by Lucy. She leads the townspeople on two levels: on the literal level, she calls the steps for the dancers of “A Real Slow Drag”; metaphorically, she guides the people to a better life—“Marching onward.” But they march not to the military strains of a John Philip Sousa; rather, they march to a characteristically African American music—a rag, a slow rag. This finale is a fitting and glorious conclusion, summing up Joplin’s philosophy that African Americans choose education as their means to a brighter future. (King of Ragtime, 2016, 270) Although Berlin’s multifaceted interpretation encompasses the message inherent in Joplin’s lyric and the culturally appropriate music genre in which Joplin couches that message and dramatically concludes the opera, there is more. This slow march forward to a brighter future mirrors the Hampton-Tuskegee ideology—a way of thinking repeatedly driven home to the schools’ students, to potential Northern benefactors, and to white Southern neighbors, a way of thinking adopted by many other African American schools throughout the former slave states, including Sedalia's George R. Smith College, which Joplin had attended.

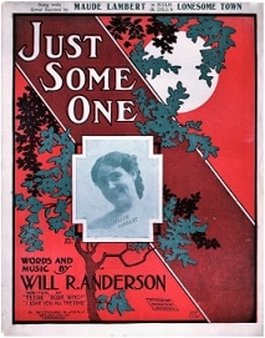

Will R. Anderson, the author of Just Someone, by far the catchiest little song, both to melody and words that has been offered the American public in some years, has at last come out of his long, deep silence and told how he did it. On November 21, 1911, the San Francisco Call published an an amusing anecdote about a performance simultaneously unbefitting the venue and calculatingly effective: Chico, Nov. 20. --Every little movement of the orchestra and the ushers of the Chico Baptist church had a meaning all its own when the collection was taken at the regular services. Also, a modern musical comedy tune, it as found, could be successfully grafted on the church organ pipes and bear good fruit. Furthermore, there was something like vindication for those leaders of Protestant churches who insist that the old hymn tunes may with profit be relegated to the basement while the choir loft devotes itself to something more modern. O'Hare's piano roll arrangement

|

AuthorI am a retired community college professor and the great-granddaughter of composer, orchestrator, arranger, organist, and teacher William Christopher O'Hare. Click the "Read More" link to see each full blog entry.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed